WE CARRY THE LAND

Los Angeles, CA (Craft Contemporary)

Co-Designer, Constructor

Team: Celina Brownotter, Anjelica S. Gallegos, Freeland Livingston, Selina Martinez, Bobby Joe Smith, Zoë Toledo.

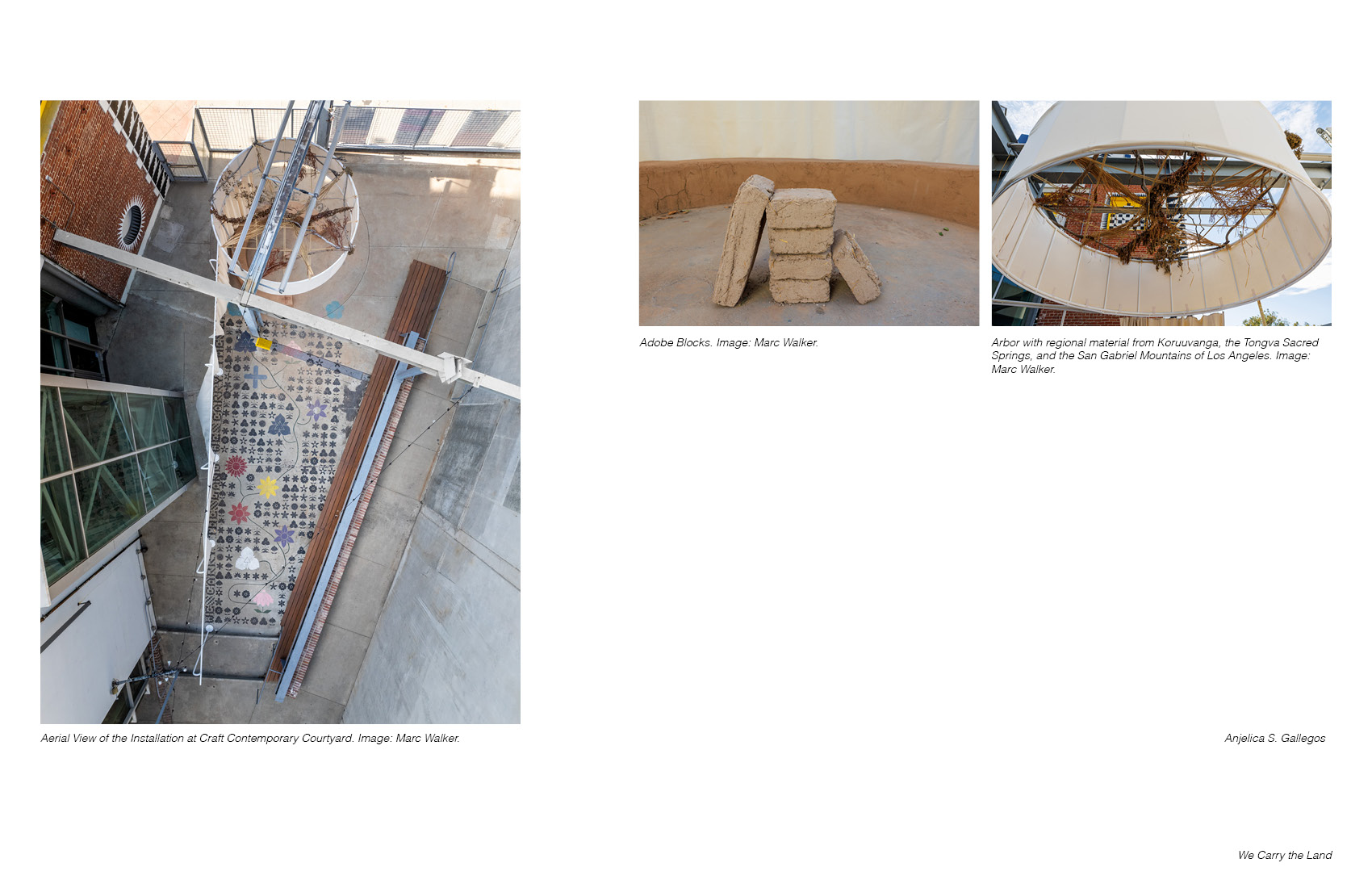

We Carry the Land is an architectural exploration of space, time, and form born from an alignment of varied Indigenous foundational ways of being. Rooted in the sacredness of the natural world and informed by experiences of territorial geographic relocation, the project presents a spatial identity of what it means to be Indigenous in 2024; grounded, yet simultaneously flexible.

Through material and structural engagement with existing infrastructure, the project introduces a fluctuating experience of the sacred and intimate to the Craft Contemporary x M&A Courtyard. An existing circle inscribed in the courtyard’s concrete ground, the remnant of a primary entry revolving door for a building that once stood in the space, becomes an anchor for the spatial intervention. In its place, a new circle is built up with heavy earth and juxtaposed with the soft lightness of a flowing curtain system above. While the earthen material highlights the circle, a unifying symbol in various Indigenous cultures, the curtain system extends across the courtyard, representing expansive transformation and the dynamism of movements and exchanges between pasts and possible futures.

We Carry the Land is designed by six emerging Native architectural and graphic designers. Recognizing the diversity of Indian Tribes, individual identities, and shared experiences with U.S. Indian laws and policies, the group work reflects a coming together of unique communities, spatial experiences with multiple lands and waters, archival work, and traditional and new technologies. We Carry the Land presents the two-fold idea of anomaly: the paradoxical notion of a dynamic ground plane and the enduring presence of American Indian peoples despite efforts of erasure.

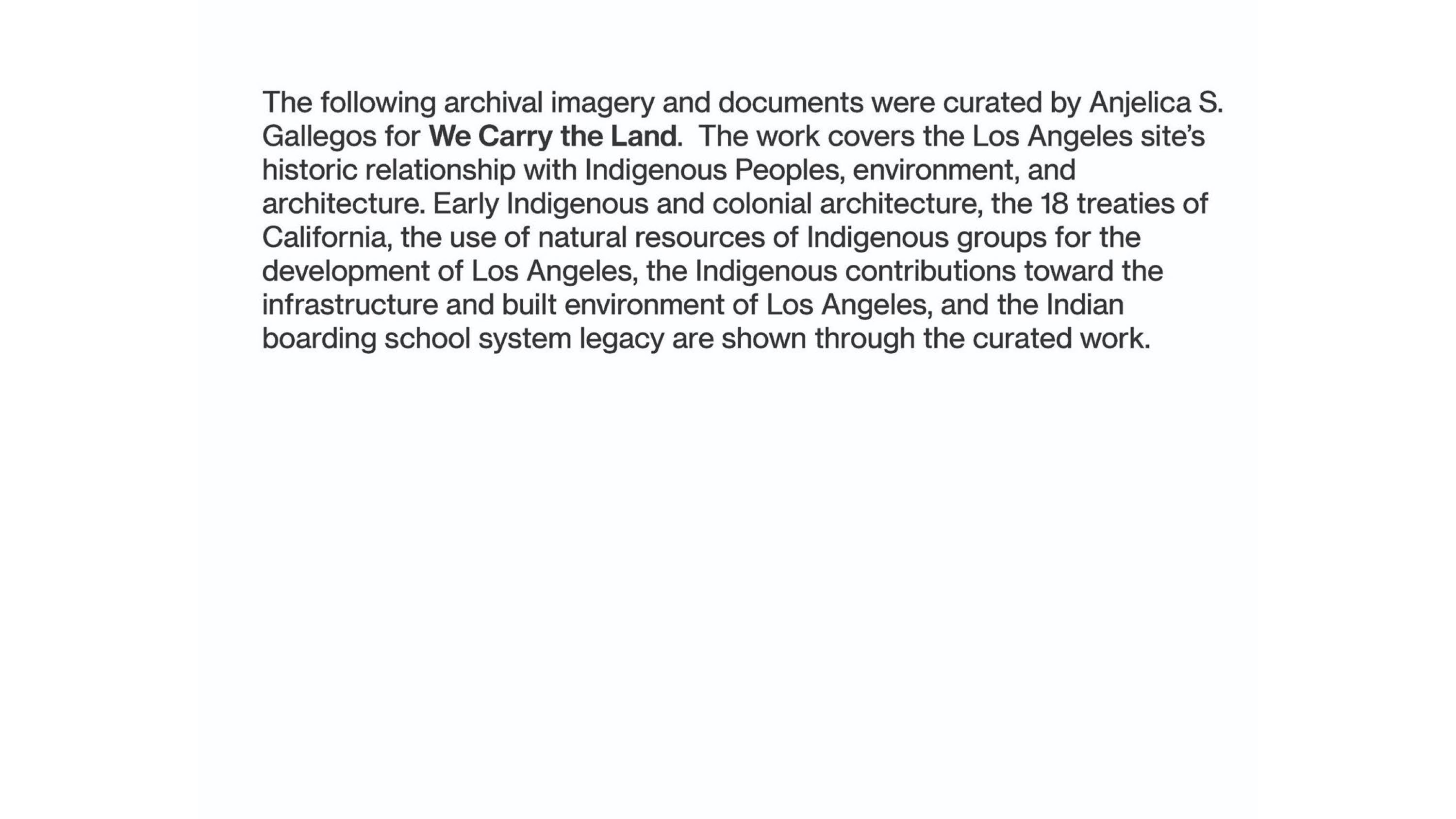

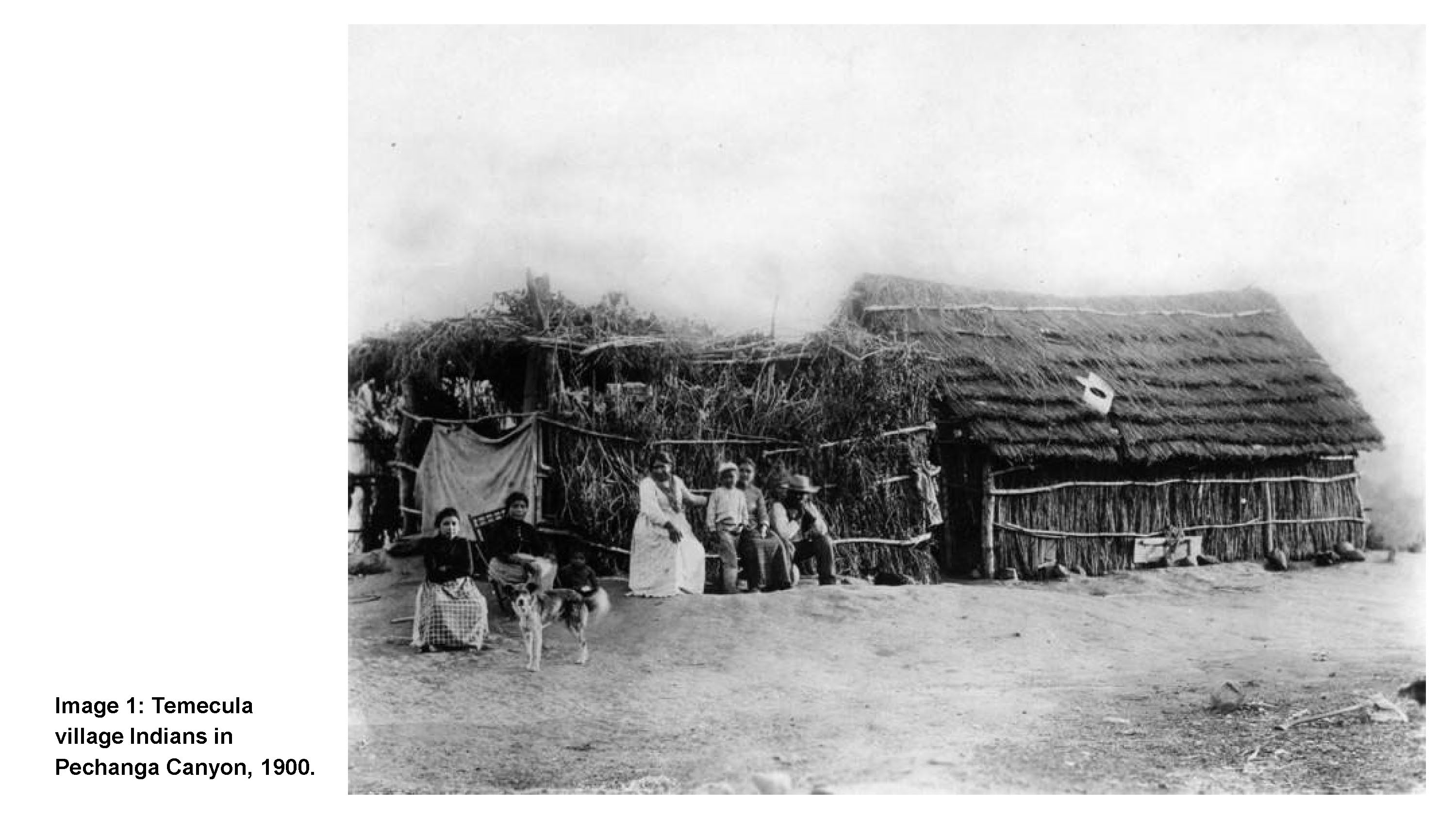

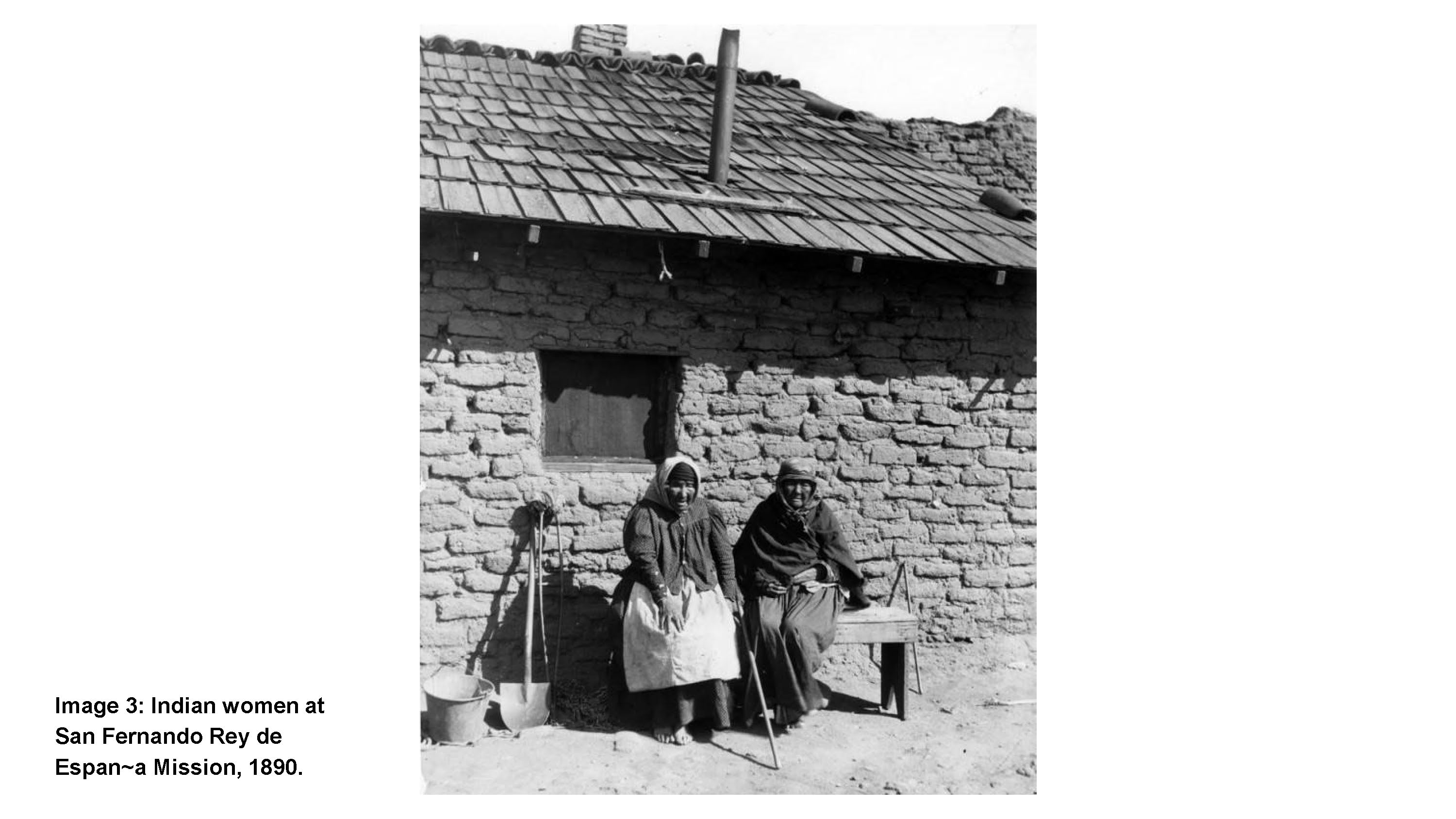

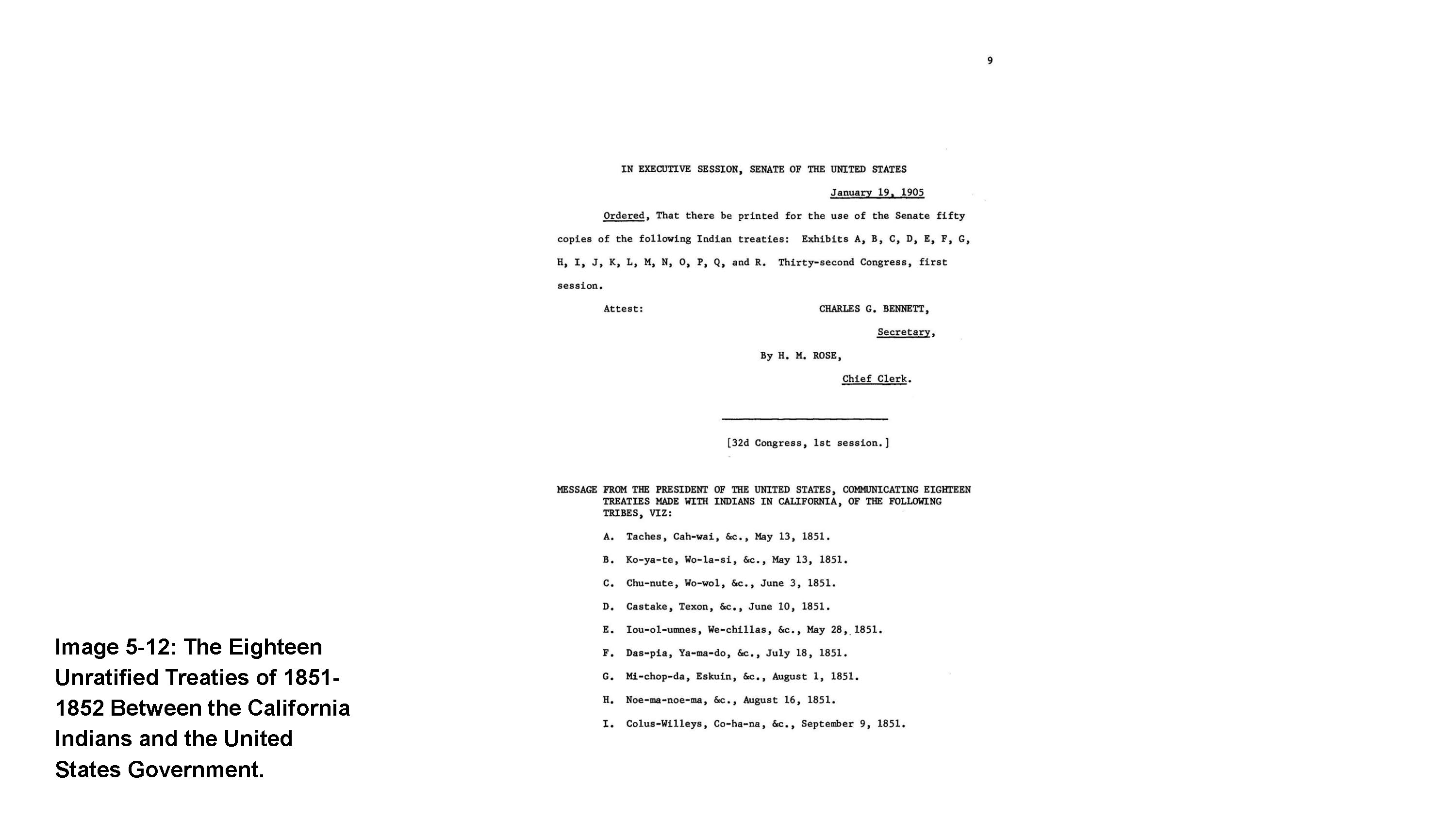

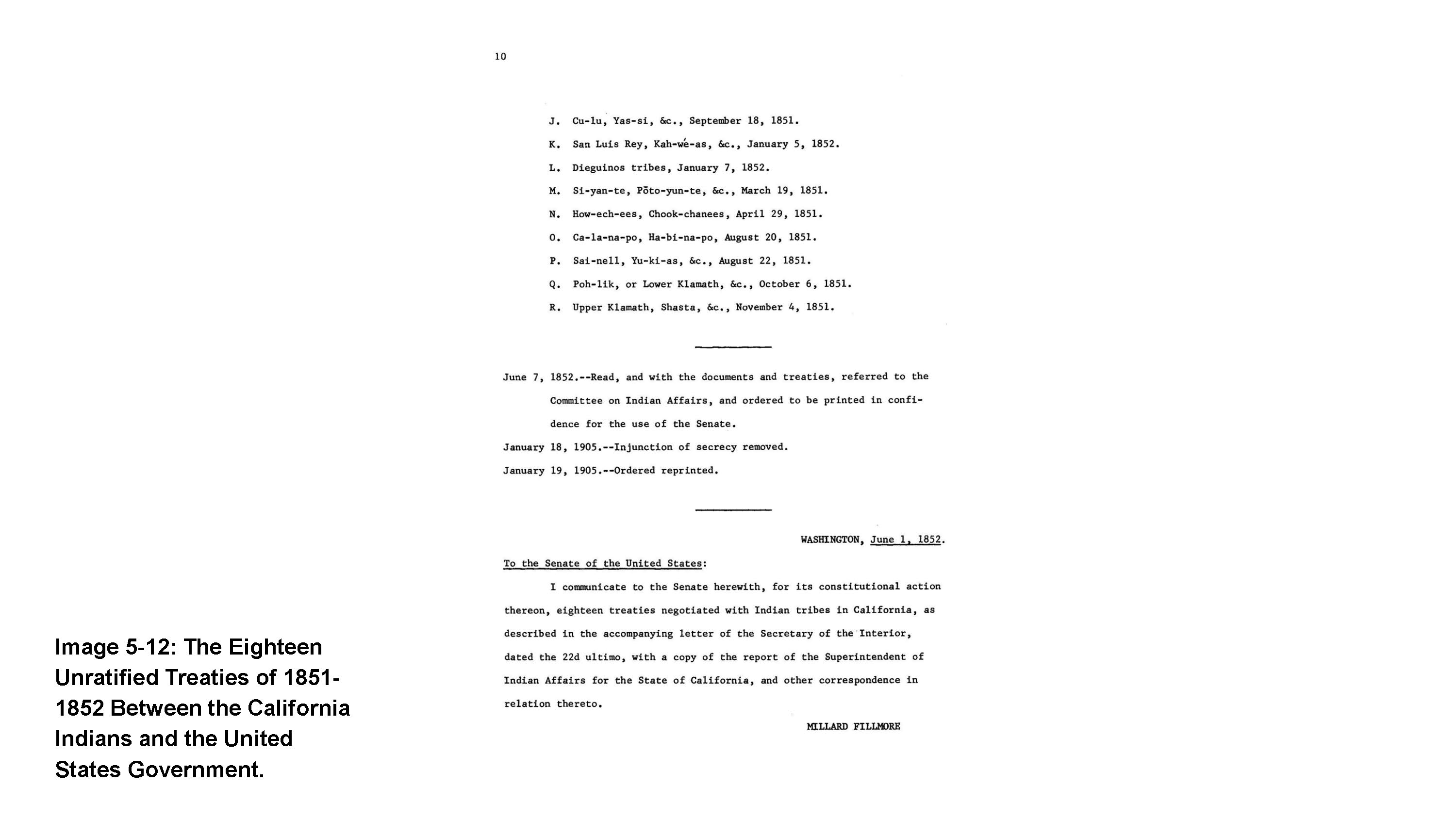

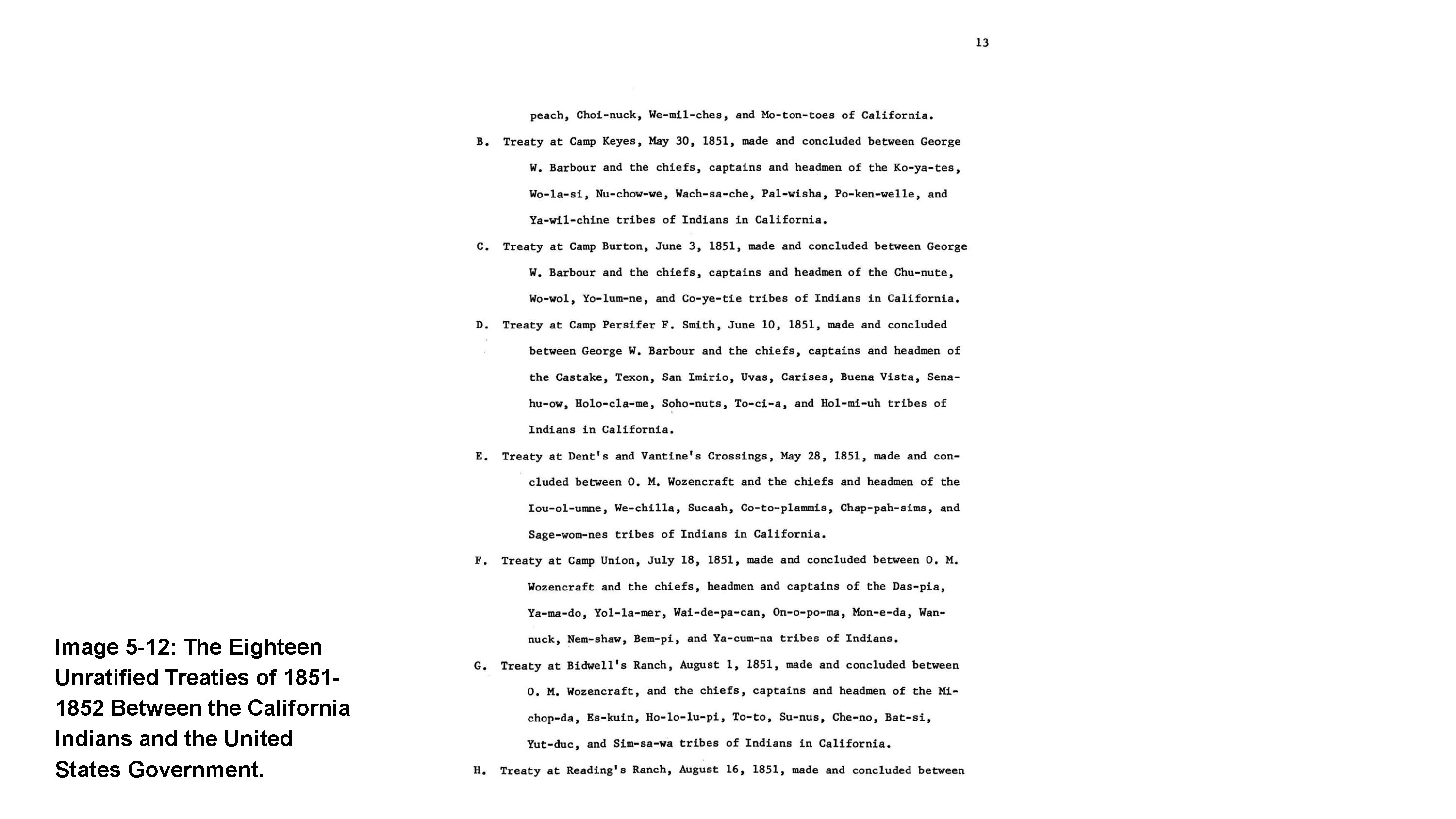

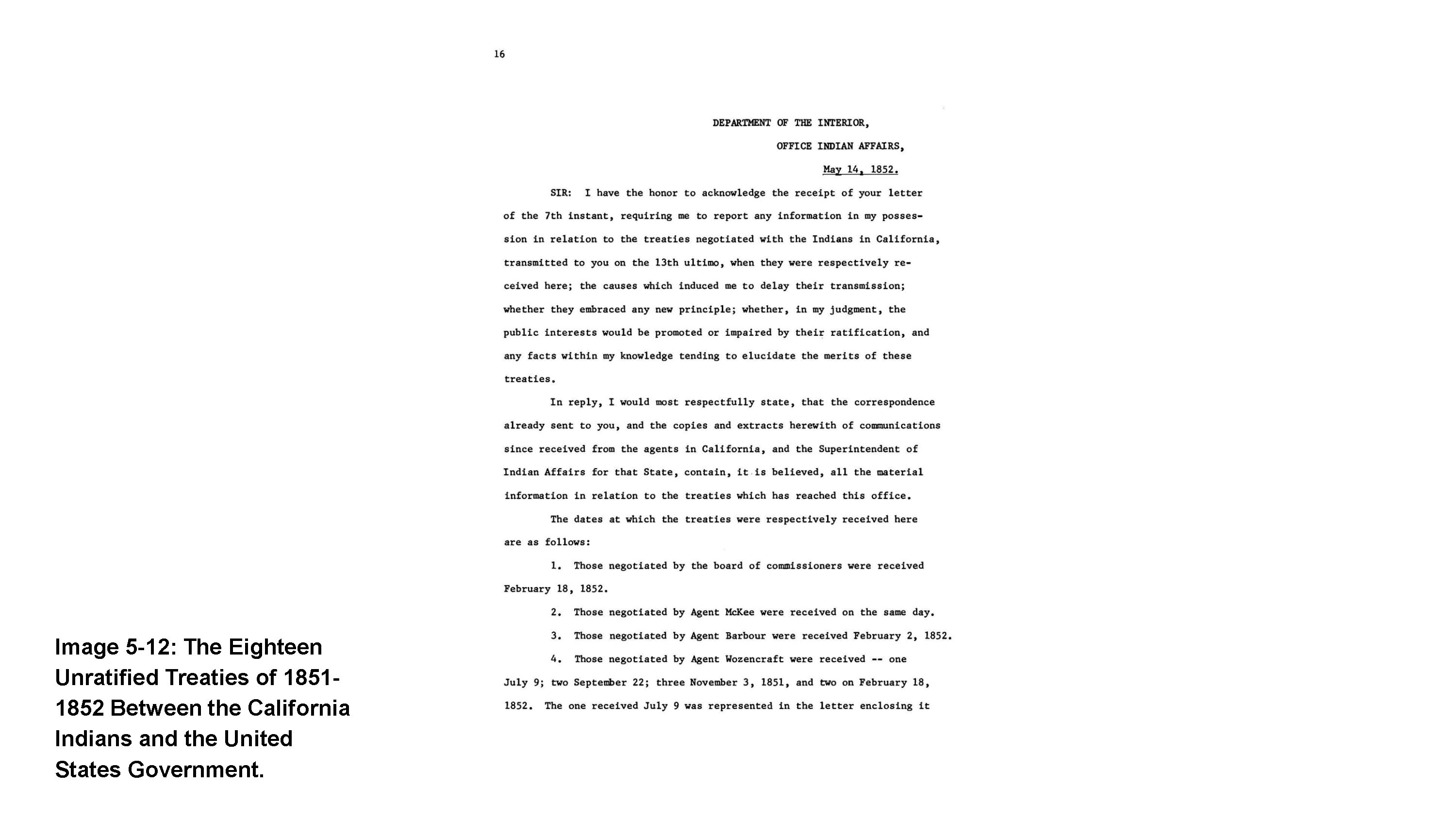

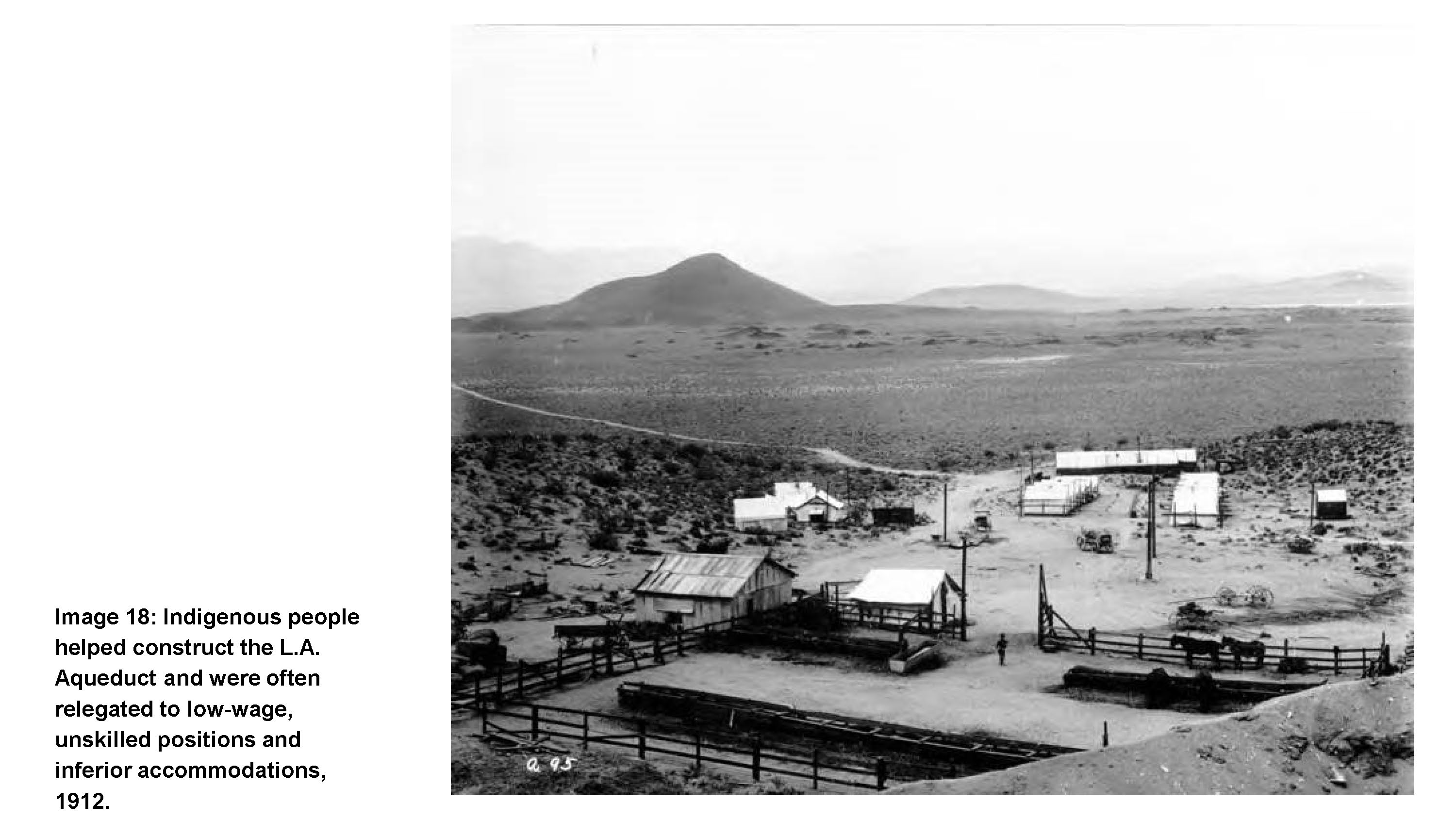

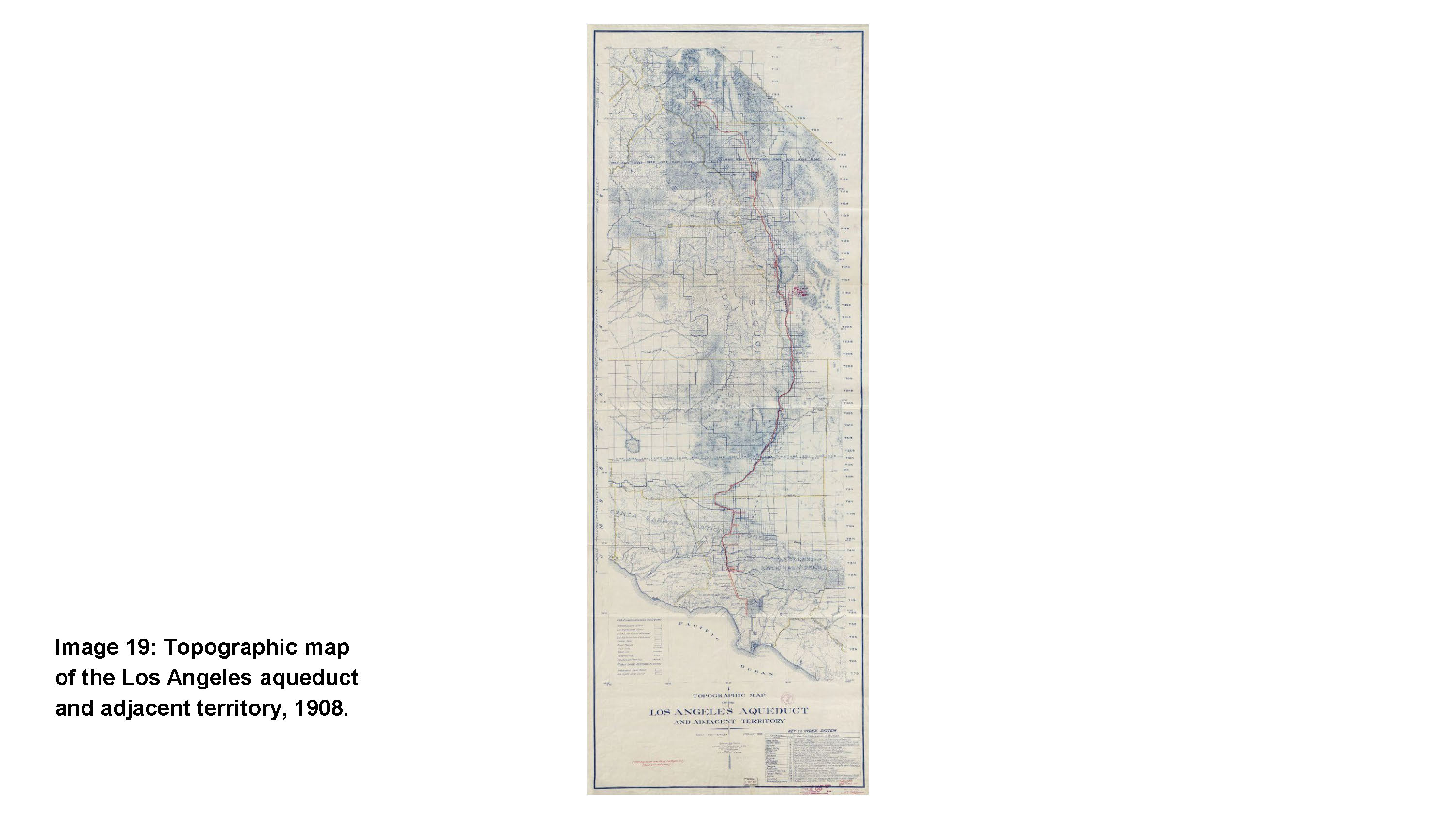

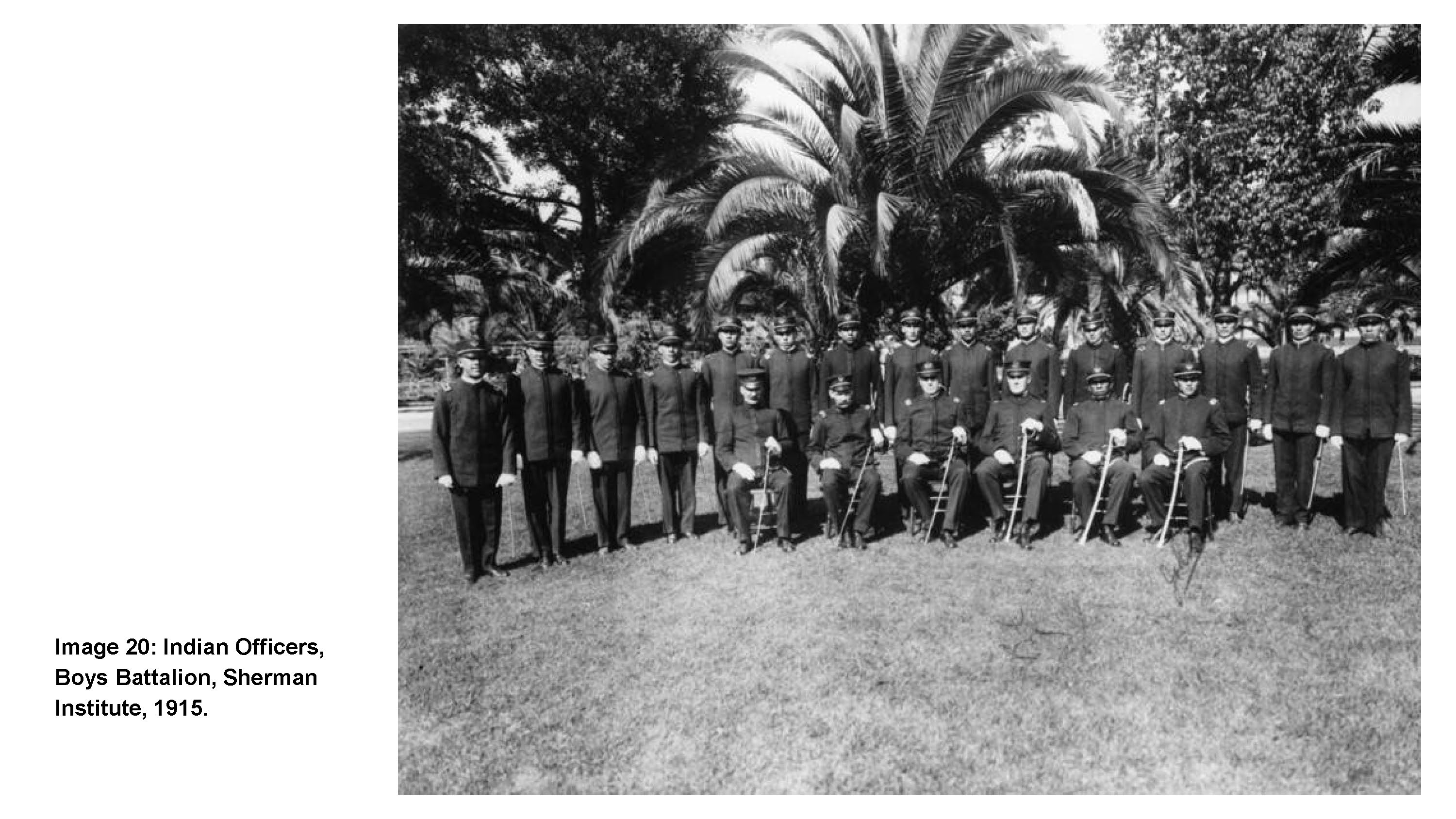

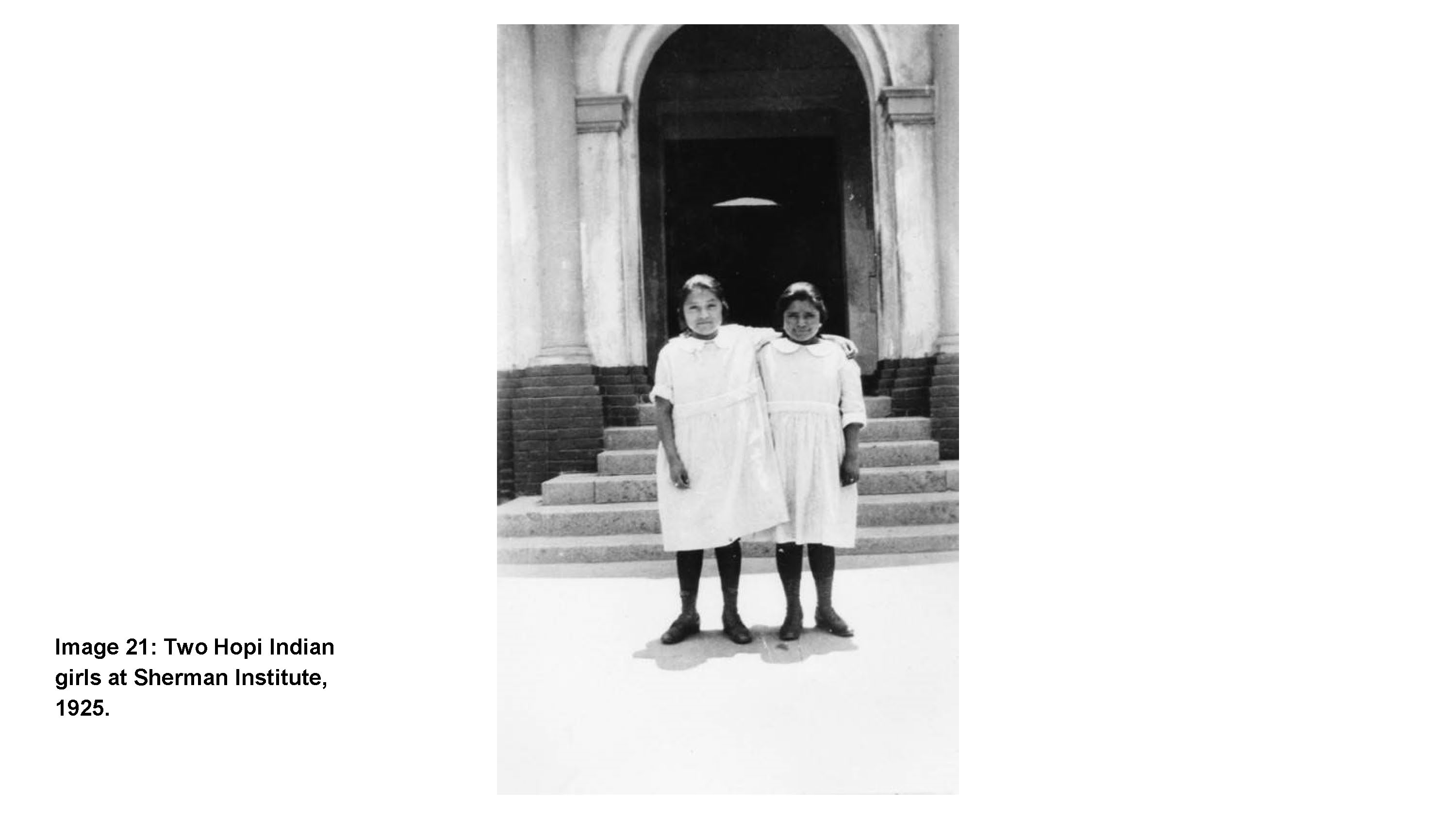

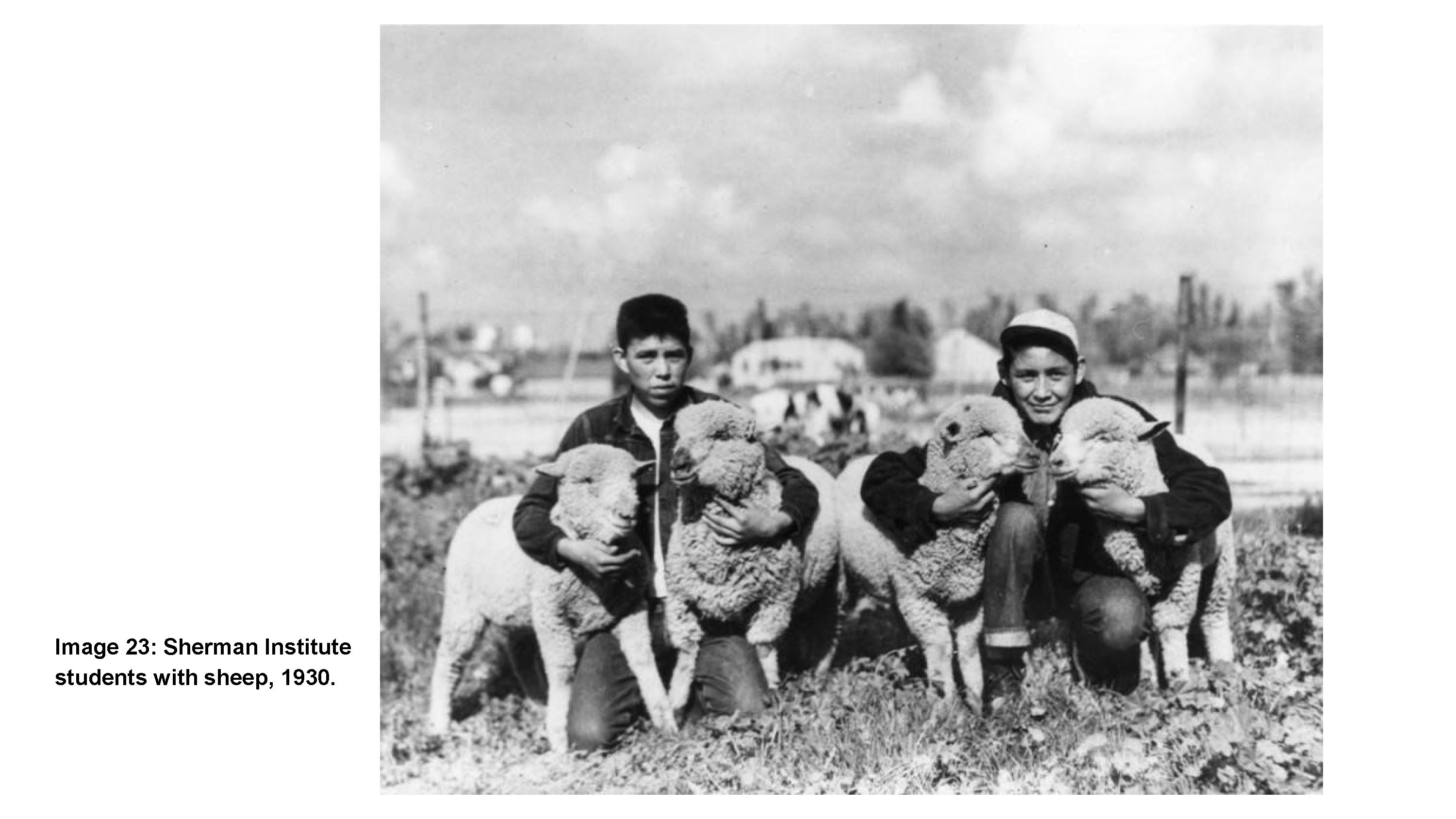

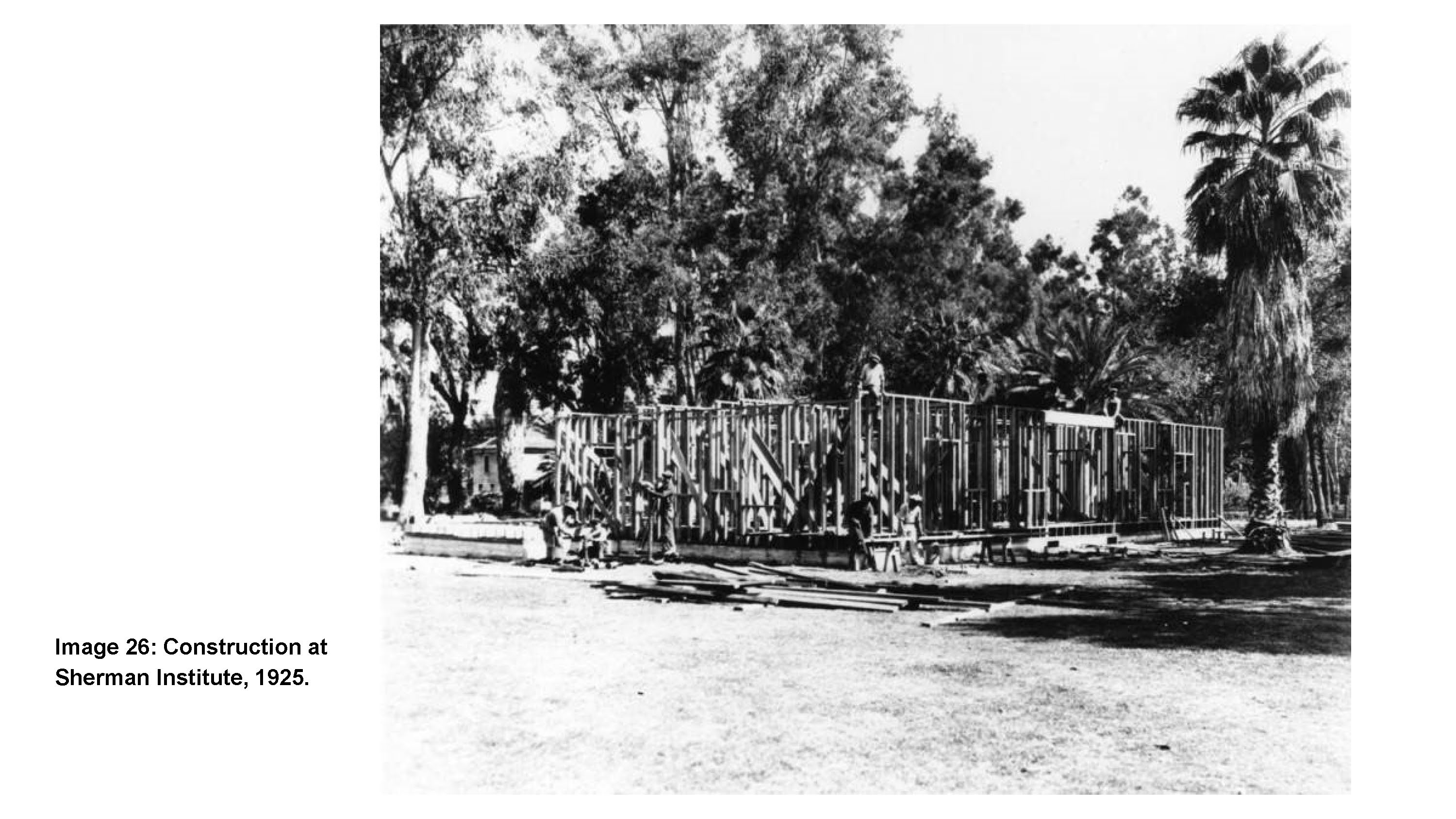

28 archival imagery and documents were curated by Anjelica S. Gallegos to project onto the We Carry the Land installation. The work covers the Los Angeles site’s historic relationship with Indigenous Peoples, environment, and architecture. Early Indigenous and colonial architecture, the 18 treaties of California, the use of natural resources of Indigenous groups for the development of Los Angeles, the Indigenous contributions toward the infrastructure and built environment of Los Angeles, and the Indian boarding school system legacy are shown.

As a program for Materials and Applications, throughout the summer of 2024, We Carry the Land included workshops, storytelling, shared meals, and other events cultivating community and kinship. Together with nearby and distant program partners, events centered on rethinking relationships to land through reorienting, reinforcing communal support through extending, and challenging and energizing ideas through Indigenous futuring.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

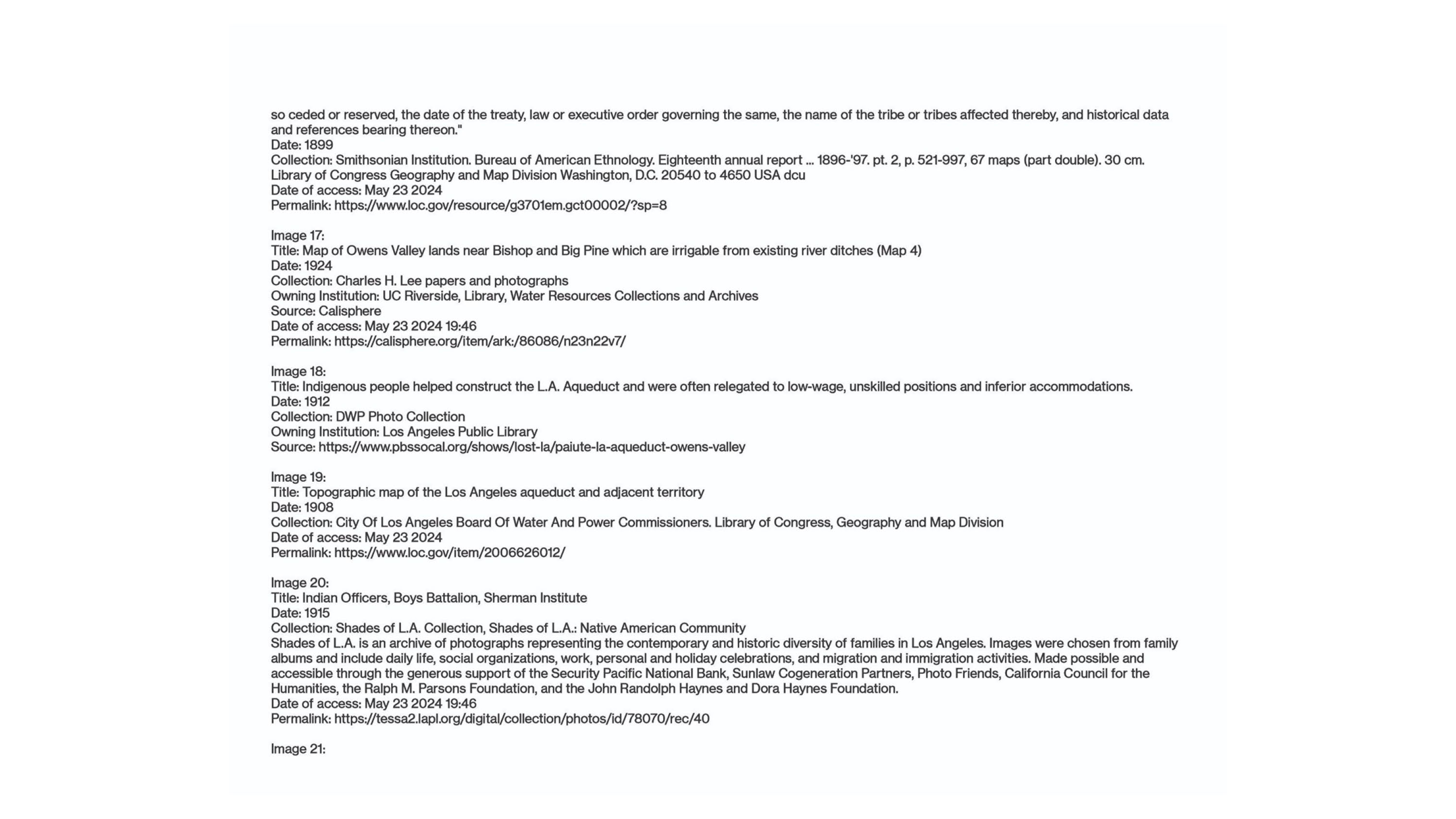

THE EQUINOX HOUSE

Albuquerque, NM (Valle de Oro National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center)

New York City, NY (Davies Toews Architecture)

Co-Designer, Constructor

Team: Miriam Diddy, Anjelica S. Gallegos

The spatial installation is a temporal travel bound structure that embodies celestial alignment and foreshadows dwelling practices of an Indigenous future. Temporary construction techniques, regional materiality, textile practices, and directional alignment are composed to reignite architectural knowledge of seasonal shift and natural cycles in the Equinox House.

The north and south doors introduce the space and are framed with black rectangular folded felt, juxtaposing with the primary circular profile of the structure. The central column of the structure ties together internal and external elements, including the top exterior nylon skin with four apertures, representing the four winds. A multicolored woven textile representing the interconnection held with the universe was centered on top of the column while a beam on the east-west axis balanced the circular three-dimensional maps on each end. The three dimensional maps outlined and aligned with the star studded sky at sunrise and sunset, while the central column aligned with the sun at high noon, on the fall 2024 equinox that took place in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Regional materials and new lighting technologies shift based on the house’s location and visual narratives shared from community members. While the first site was the desertscape of Albuquerque and wetland of Valle de Oro, adobe, pine, juniper and cholla cactus were central to the space. For the urban north east coast location of New York City, oyster shells, moss, cattails, and water were embodied in the House.

Visual narratives of seasonal change and celestial alignment from the greater Indigenous community were projected onto the free standing structure harmonizing with the collective elements.

While in New Mexico, the House was primarily experienced in the arid day at the height of the Equinox in September. At the white gallery space in New York City, the House was activated at night in late October complementing the coastal reflective surfaces of the urban landscape.

The Equinox House was designed and constructed on site by Anjelica S. Gallegos and Miriam Diddy as part of the larger First Future Project. The endeavor was awarded a Fulcrum Fund grant made possible by 516 Arts as a partner in the Regional Regranting Program of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

The Equinox House is now located with the ISAPD Yale chapter for another future adaptation.

![]()

![]()

![]()

ENVISION RESILIENCE INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS INITIATIVE (IKSI)

Nantucket, MA

Remain Nantucket initiated the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Initiative (IKSI) to respectfully acknowledge Indigenous historical and contemporary ties to the Envision Resilience Challenge sites.

The IKSI Working Syllabus provides curated resources for Envision Resilience Challenge participants and the general public to strengthen design approaches as we move forward in informed stewardship with all communities.

IKSI was created with the support of Anjelica S. Gallegos (Jicarilla Apache Nation/Santa Ana Pueblo), a member of the first Envision Resilience Challenge student cohort, Advisor of the Envision Resilience Challenge and Director of the Indigenous Society of Architecture, Planning and Design.

https://www.envisionresilience.org/iksi

![]()

MAINE TRIBAL LANDS

Remote Location

Private Client

![]()

YALE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE TRIBAL LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

New Haven, CT

Project Origin:

This project was initiated as a collaborative effort between Indigenous Scholars (Society) of Architecture, Planning and Design co-founders Anjelica S. Gallegos (MArch I ’21) with Summer Sutton (Architecture PhD ’22), and Dean Deborah Berke, and Yale School of Architecture leadership. The project was accomplished with the support of the Yale Native American Cultural Center and Yale student members from classes 2019 to 2024.

Yale School of Architecture Tribal Land Acknowledgement Statement:

The Yale School of Architecture sits on traditional Indigenous territories. This includes lands of the Mohegan, Mohican, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, Quinnipiac, and other Algonquian speaking peoples. We pay respect to their peoples of past and present.

Yale University and Yale School of Architecture have benefitted from lands gained through fulfilled and unfulfilled articles of agreement with Indigenous nations and from land cession of Indigenous territories.

The Indigenous peoples who have stewarded these lands for time immemorial remain impacted by discussions of space and place. Yale School of Architecture will continue to work, advance, and teach these histories in architectural education and the profession.

As mediators, we will learn from the generations before us to instill cognizant ways of being in spatial environments with shared histories. As architectural professionals, we will imagine endless possibilities for architectures of reconciliation, reciprocity and transformation; an architecture for those yet to be born, an architecture of the spirit.

![]()

Drawing Intention:

This interpretive map presents interconnected boundaries of tribal land over time and their relationship to the New Haven area. Animate and inanimate entities are woven throughout the landscape as a cohesive system.

The orthogonal lines coming from the west, north and east, connect to the center of New Haven’s nine square grid, and indicate the historical Quinnipiac travel routes that linked the Quinnipiac with the Paugussetts, Wangunk and Mattabesett, Hammonasset and Niantic peoples.

The topography lines above the nine square grid, represent Hobbomock mountain, now known as Sleeping Giant. Hobbomock mountain is a landmark and significant place within Quinnipiac origin stories and connected with surrounding New Haven topography history.

https://www.architecture.yale.edu/about-the-school/tribal-land-acknowledgement

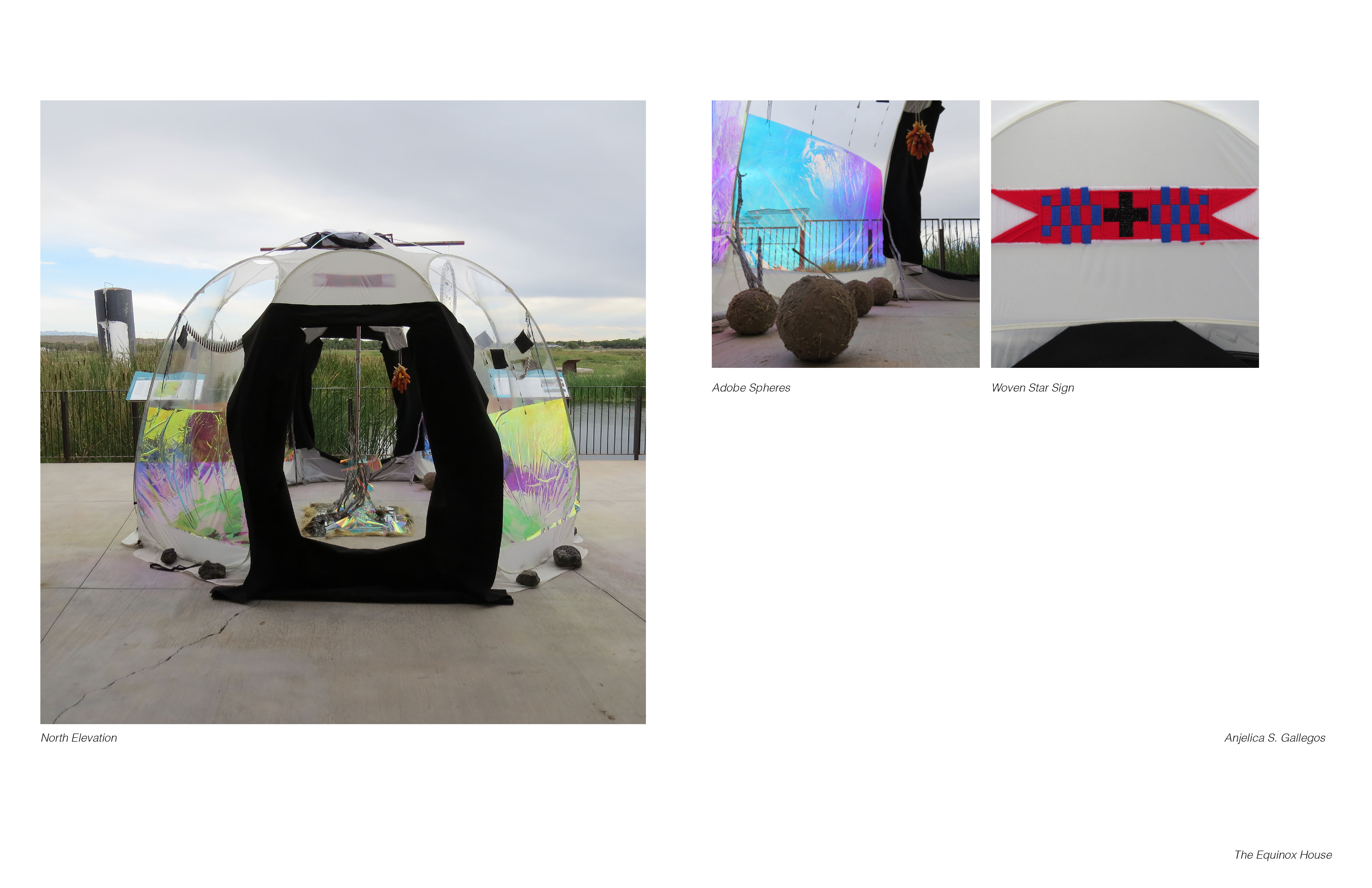

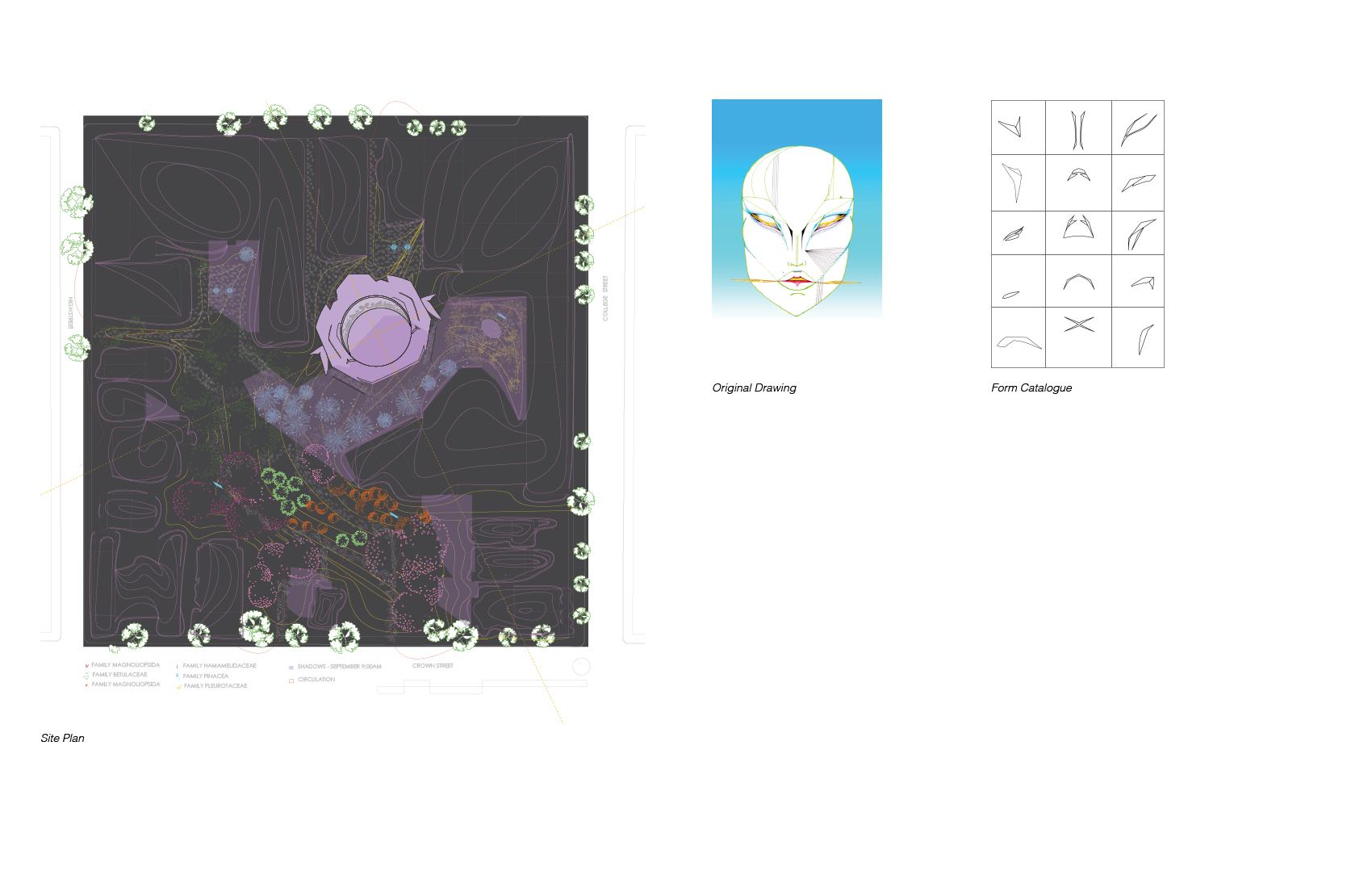

PLAN, UNPLANNED

Contemporary Art Museum

New Haven, CT

Architectural Design Studio I

Critic: Nikole Bouchard

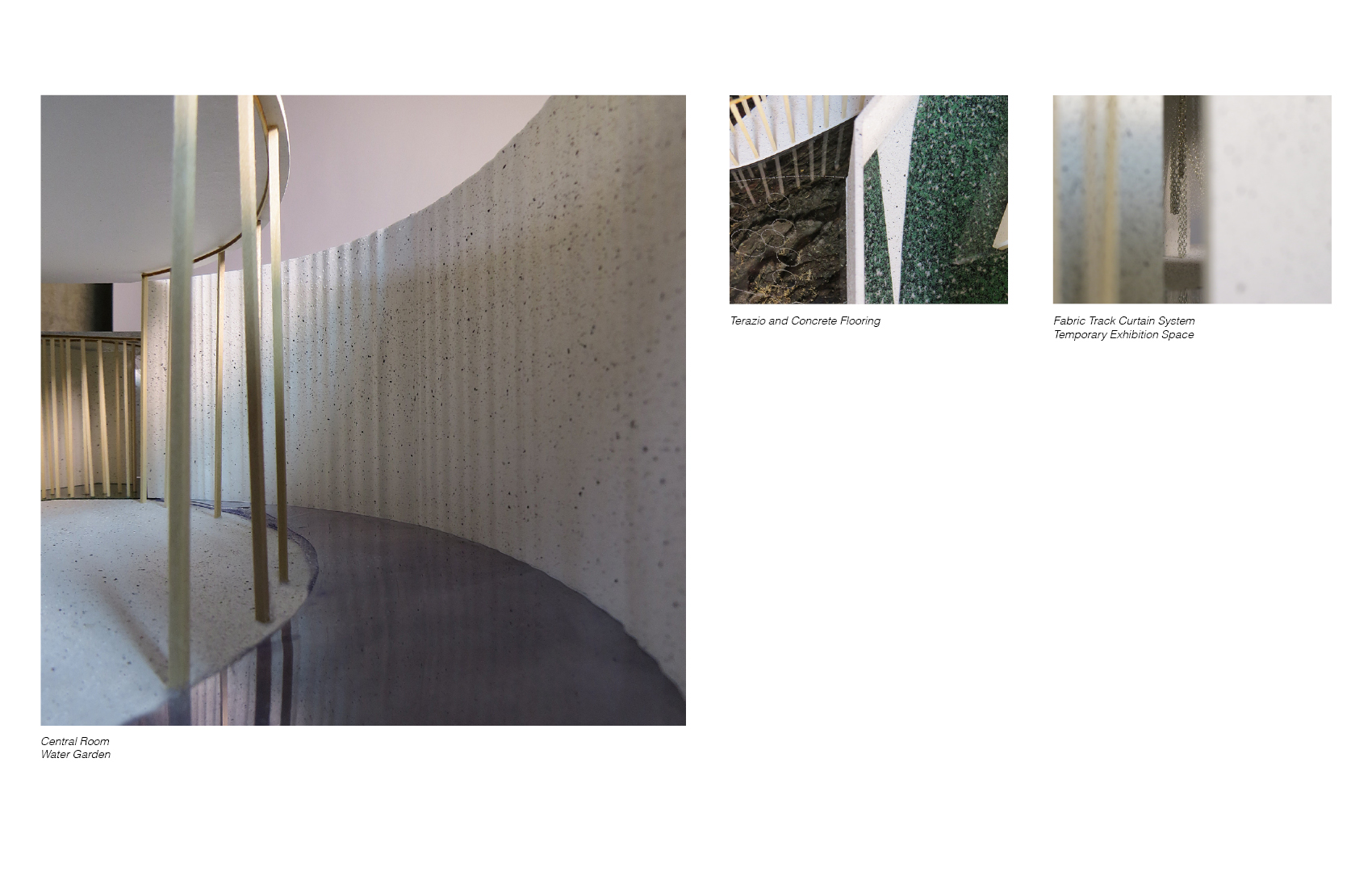

The importance of design through the plan was studied in depth during this studio. An original drawing inititated the project and was sourced as a collection of geometric forms to organize into a building form. Ultimately the plan as a tool to create spatial and social relationships was realized and strengthened. Tectonic and material specificity, site context, sun movements, ecology design, and occupation were key components in the design of the Contemporary Art Museum.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

RESTORATIVE COMMUNITY

The People’s Land Center

New Haven, CT

Architectural Design Studio III

Critic: Emily Abruzzo, Inaqui Carnicero

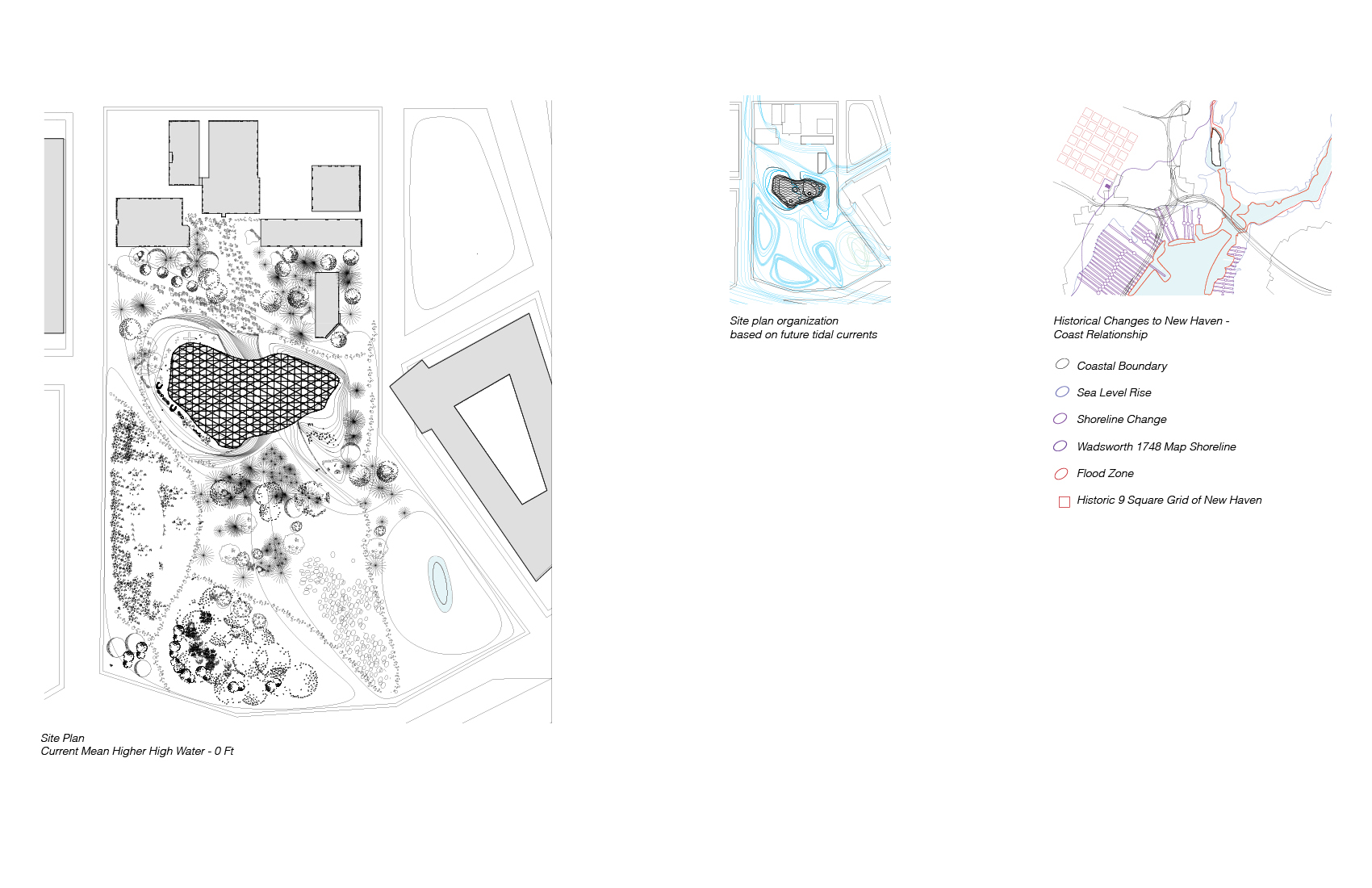

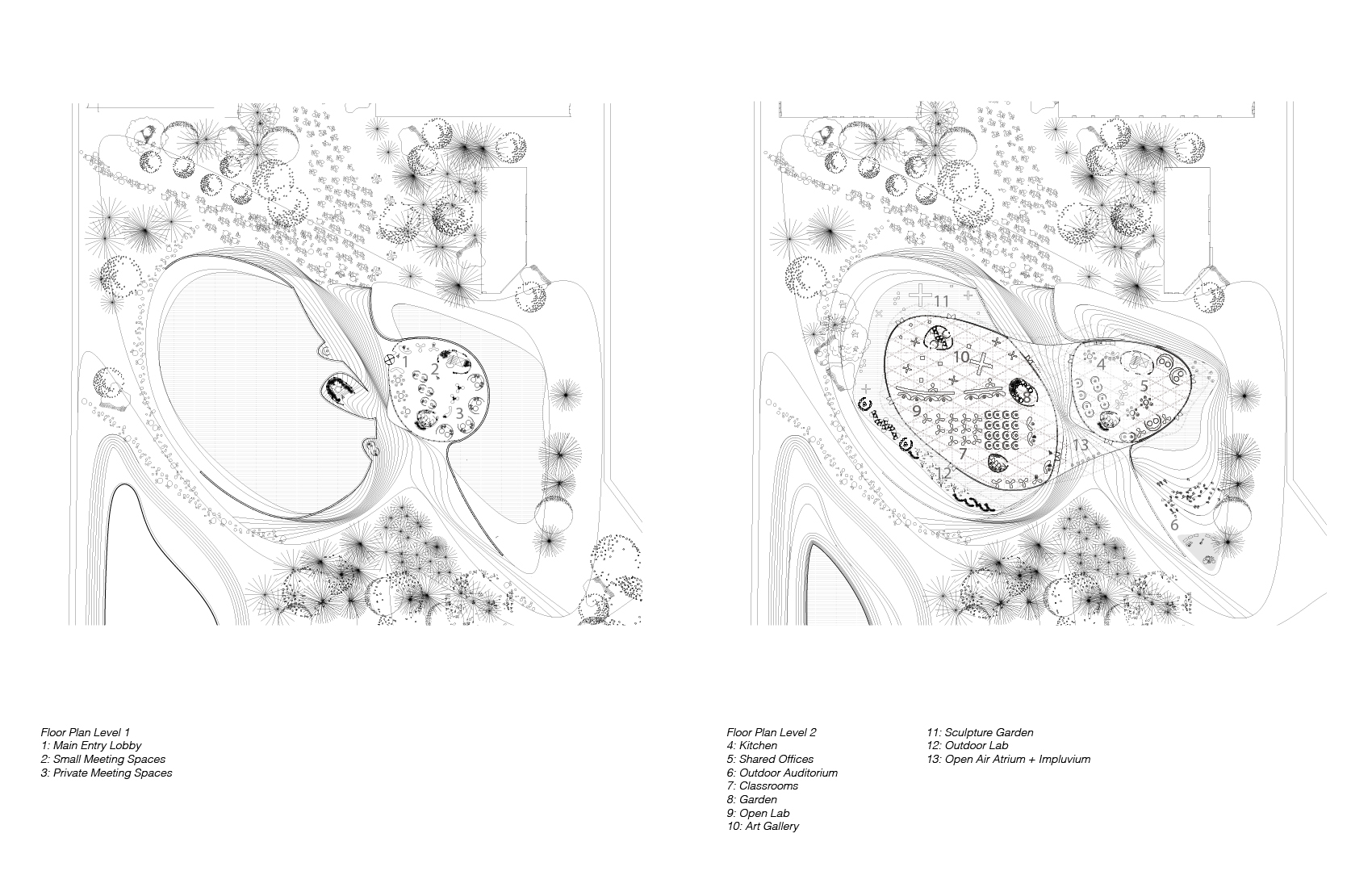

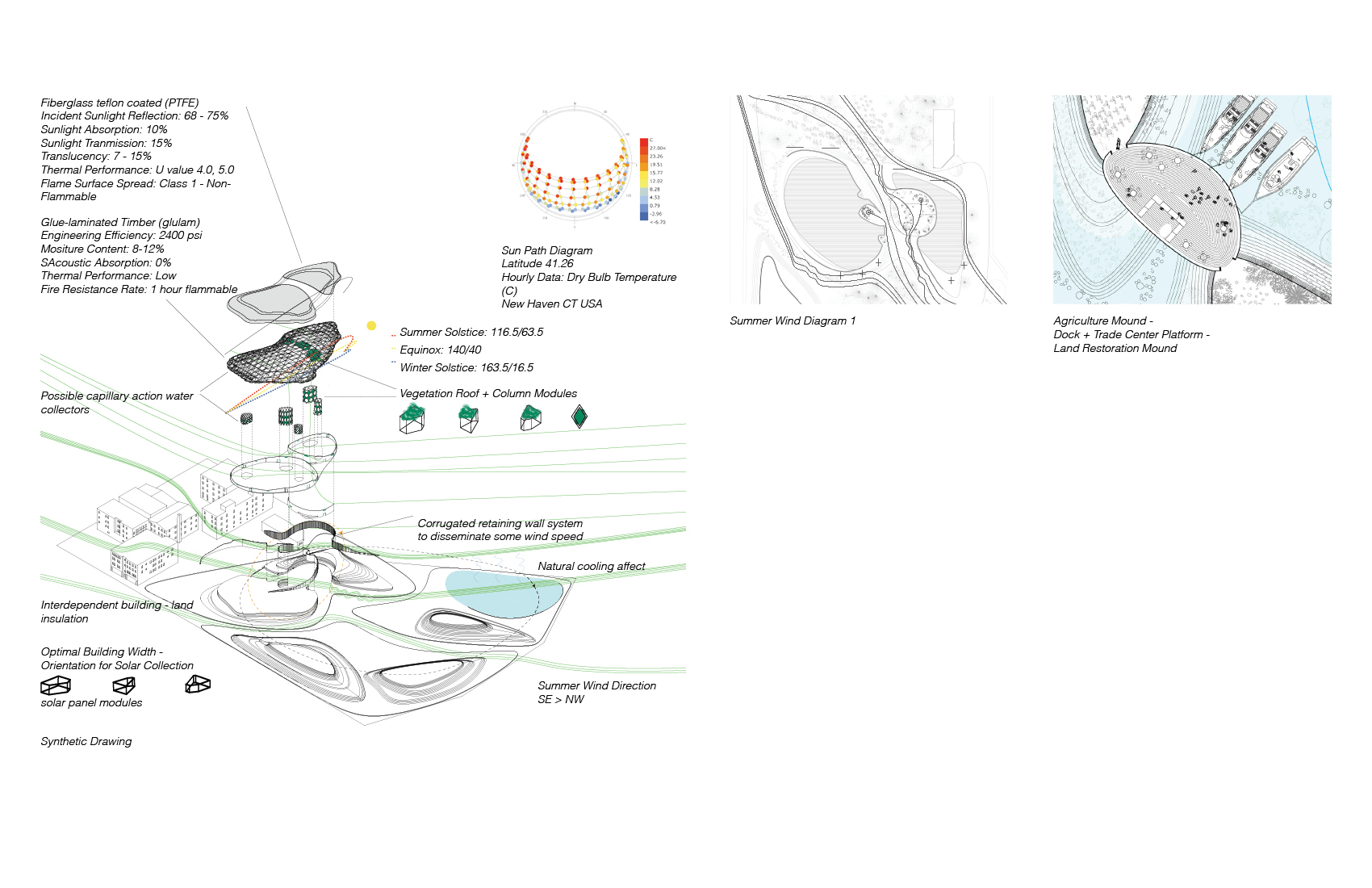

The unique history, current and future needs of the New Haven site was thoroughly researched for the design of an ecological community center. Gathering information from 19th century scholar and previous Yale President Ezra Stiles, a map of New Haven based on information from interviews with the original Indigenous peoples of the land was created with the original context of the site, noting shorelines, trails used by tribes. Further, I investigated the historical changes of the shoreline of on the harbor adjacent to the site and collected data on the future changes of the shoreline due to climate change. In an effort to generate a mutually restorative relationship with the natural environment, like the original land stewards had, a program centered around adaptability, learning and implementing practices related to horticulture, agriculture, water harvesting and forest restoration was established. To address current needs an open floor plan for all levels was carefully organized to incorporate needs such as immigration services. A series of man made land mounds were created to address the future need for land mass and a place to congregate.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

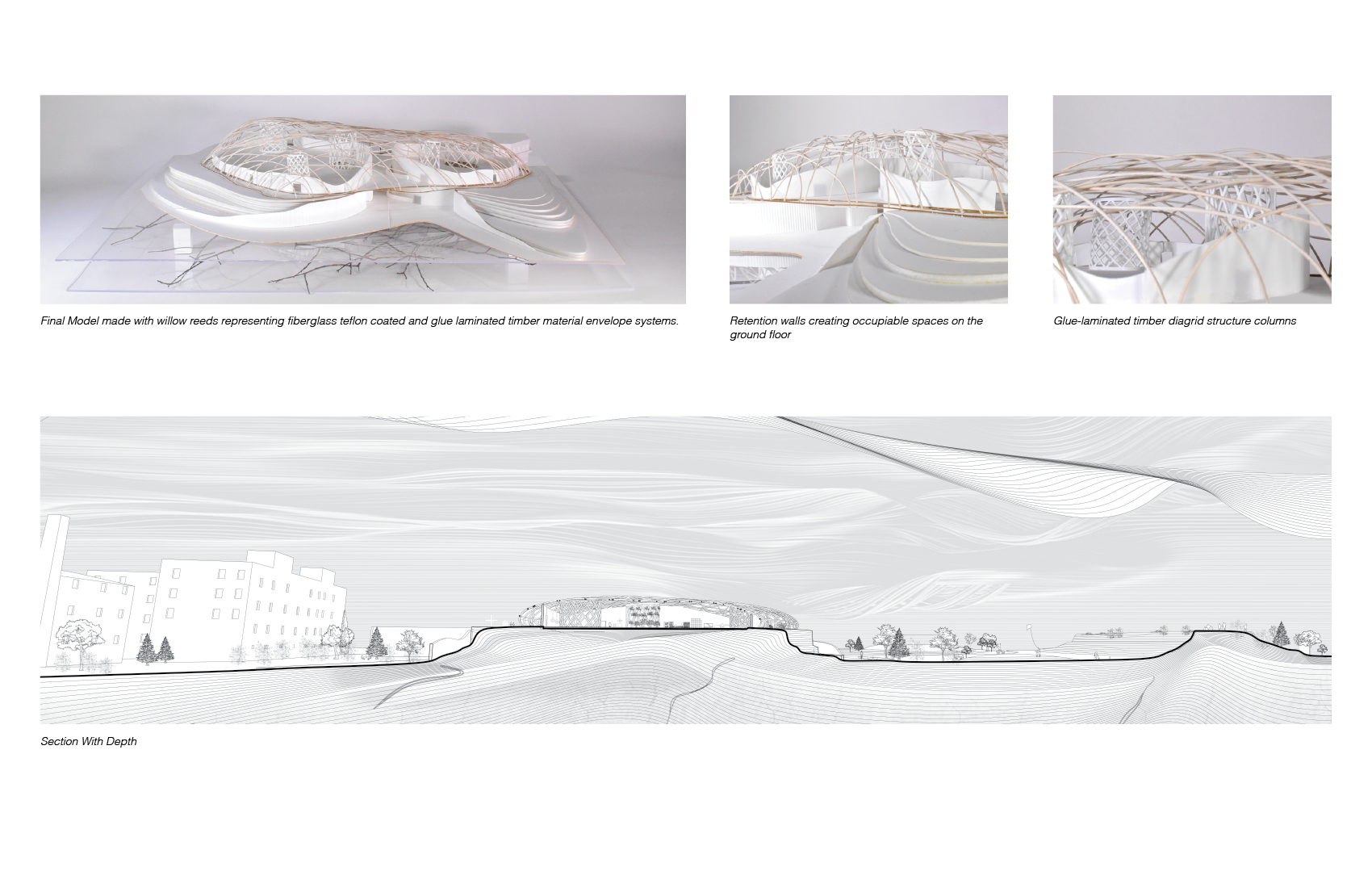

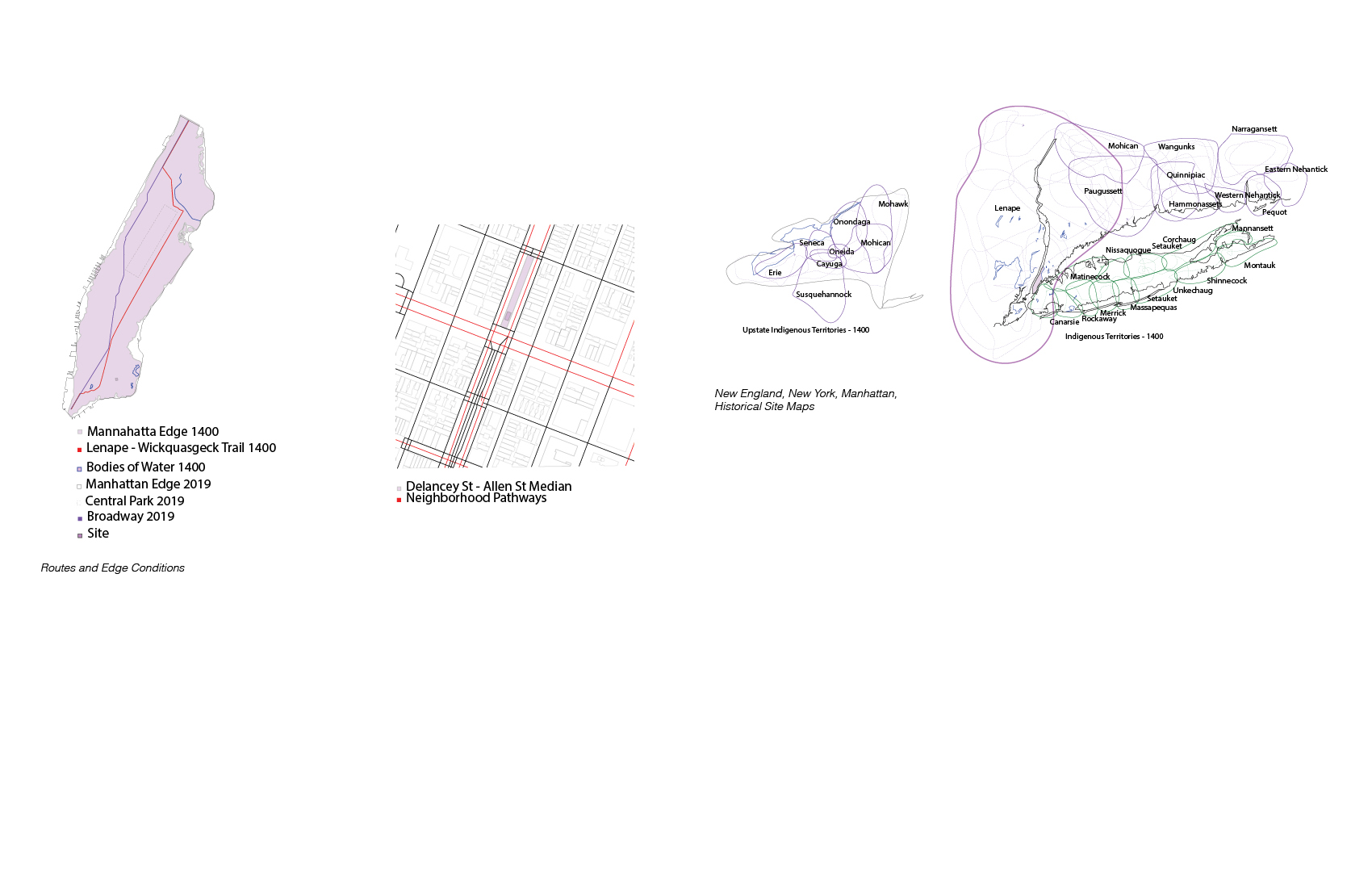

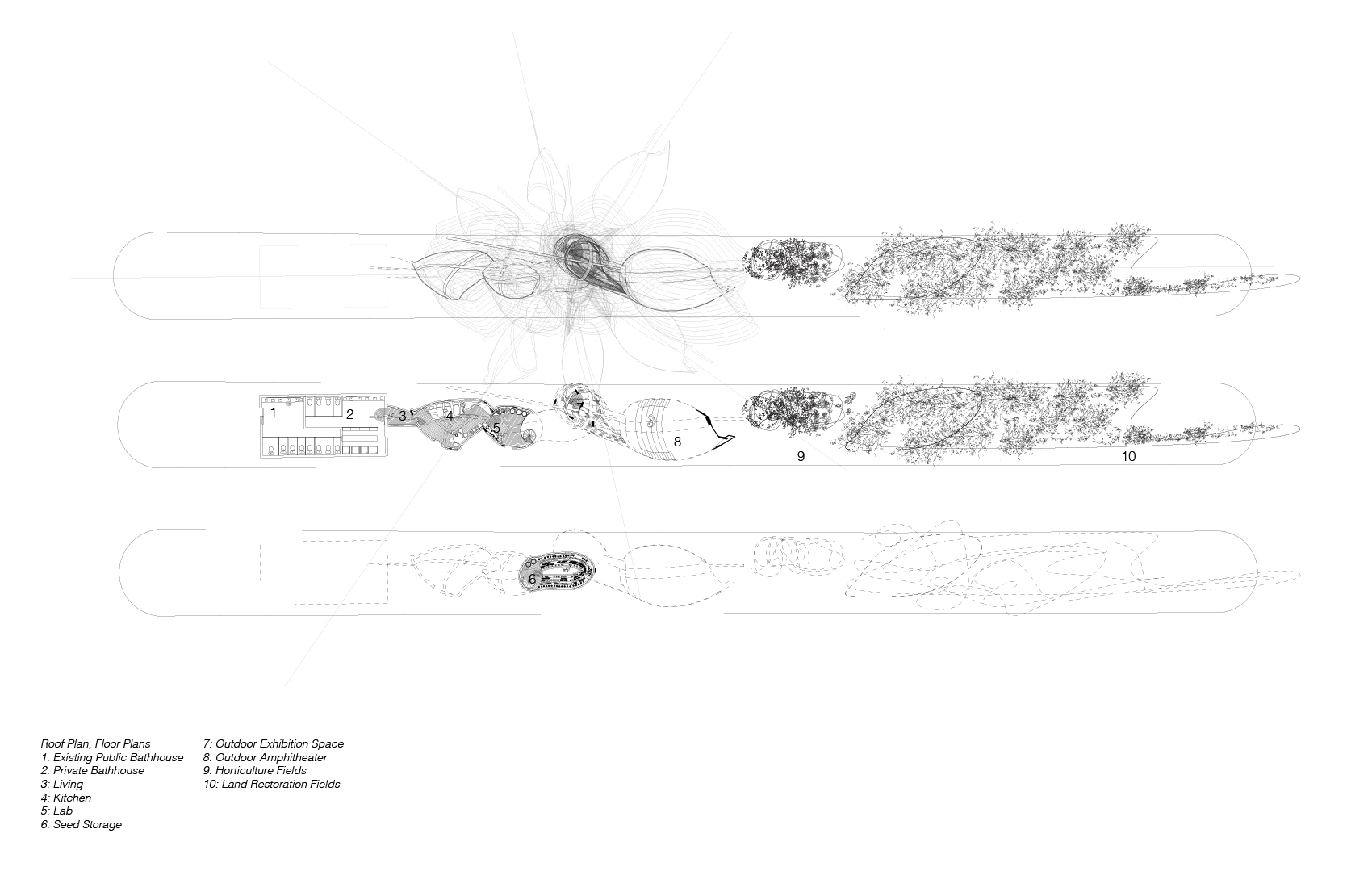

LIFE, AFTERLIFE

Indigenous Horticulture Center

Manhattan, NY

Architectural Design Studio II

Critic: Trattie Davies

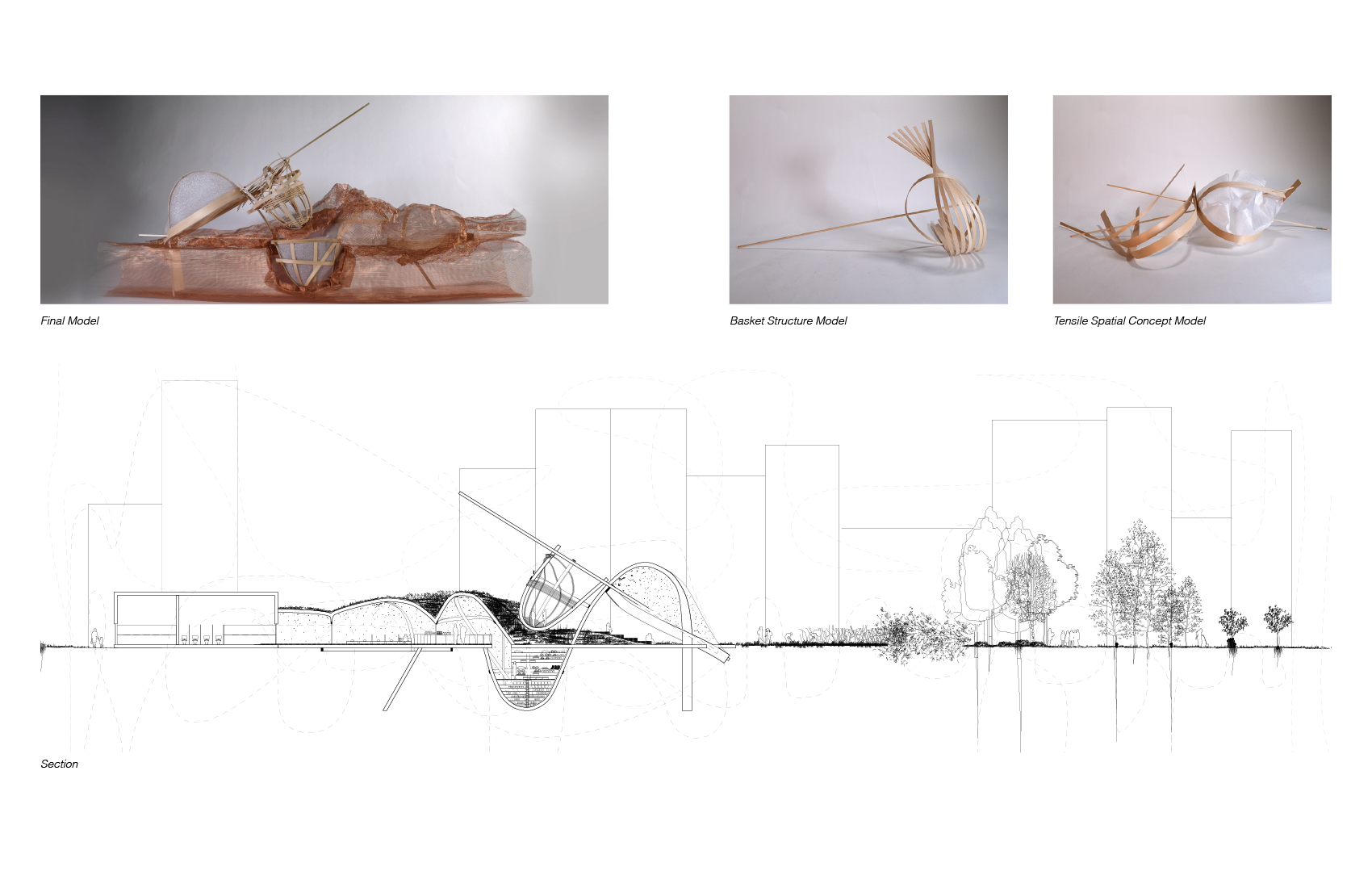

The permanence of buildings and life of materials was the focus of this studio. Designers were asked to consider how the design would change over the course of 100 years. I researched the historical context of the site including the indigenous horticulture practices used to grow food and allow for reforestation of the land. I analyzed the site changes over the next 100 years incorporating the future tide changes due to climate change. Tectonic principles in basketry and tensile structures were used as precedence for construction.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

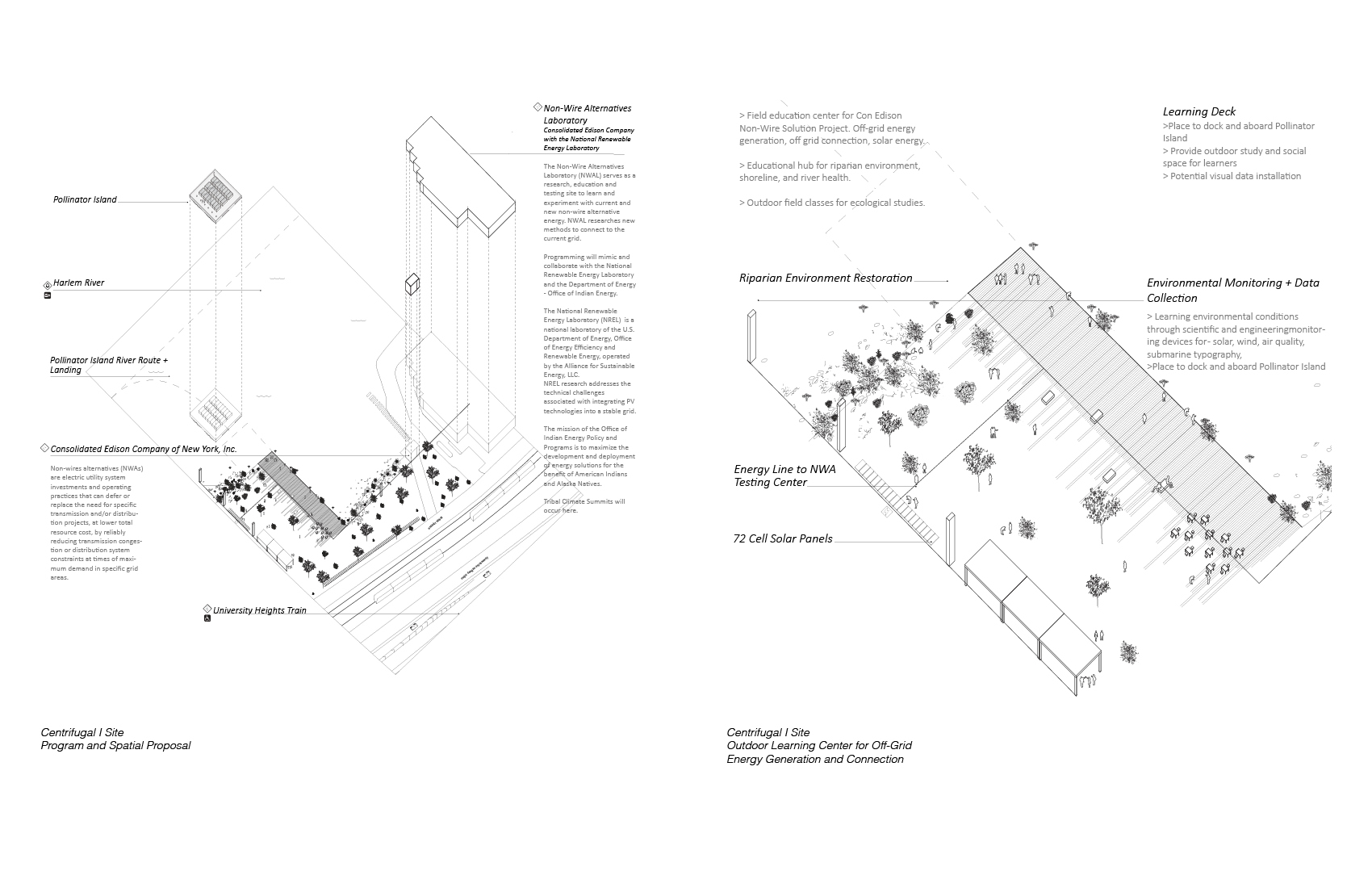

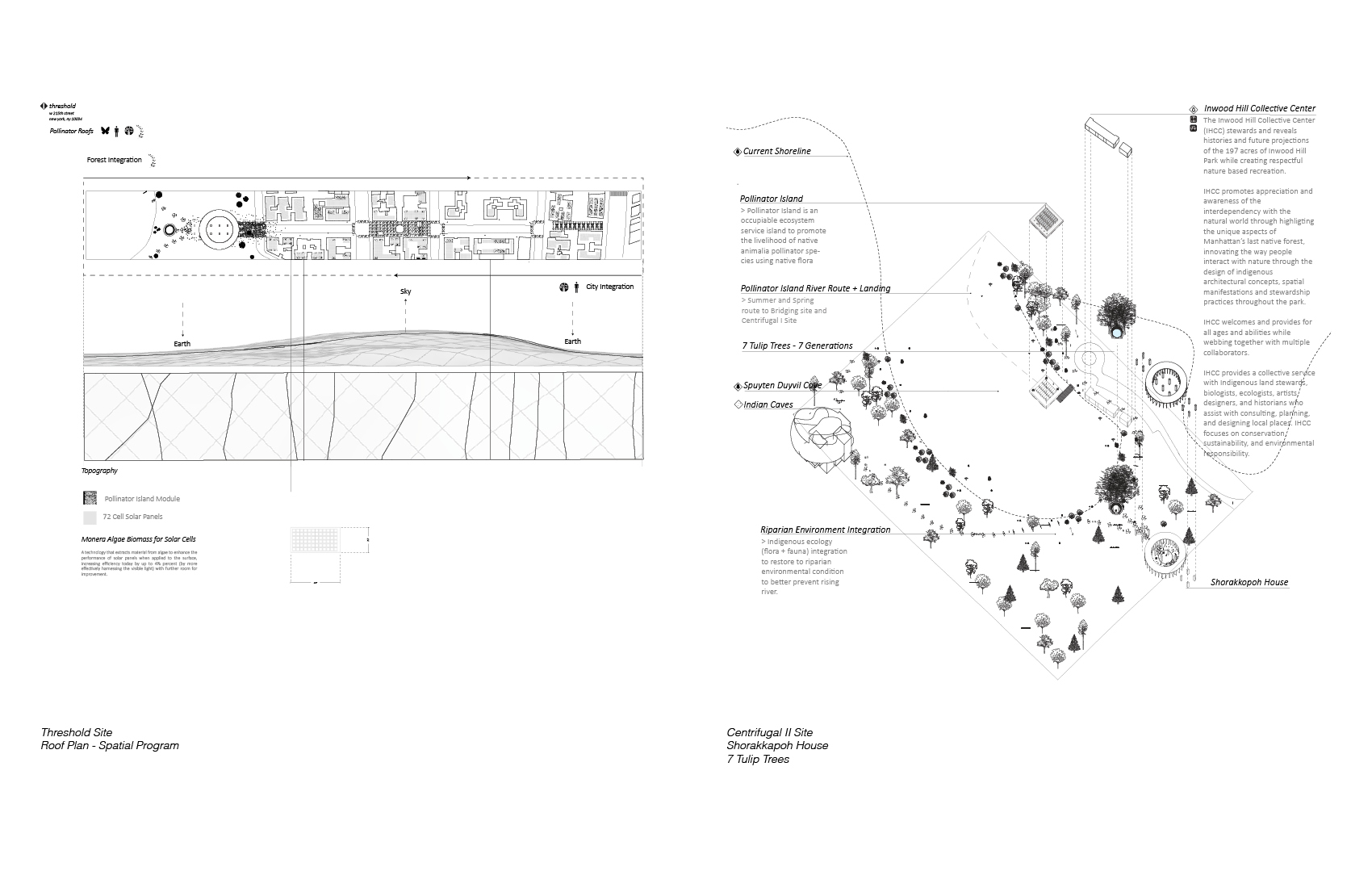

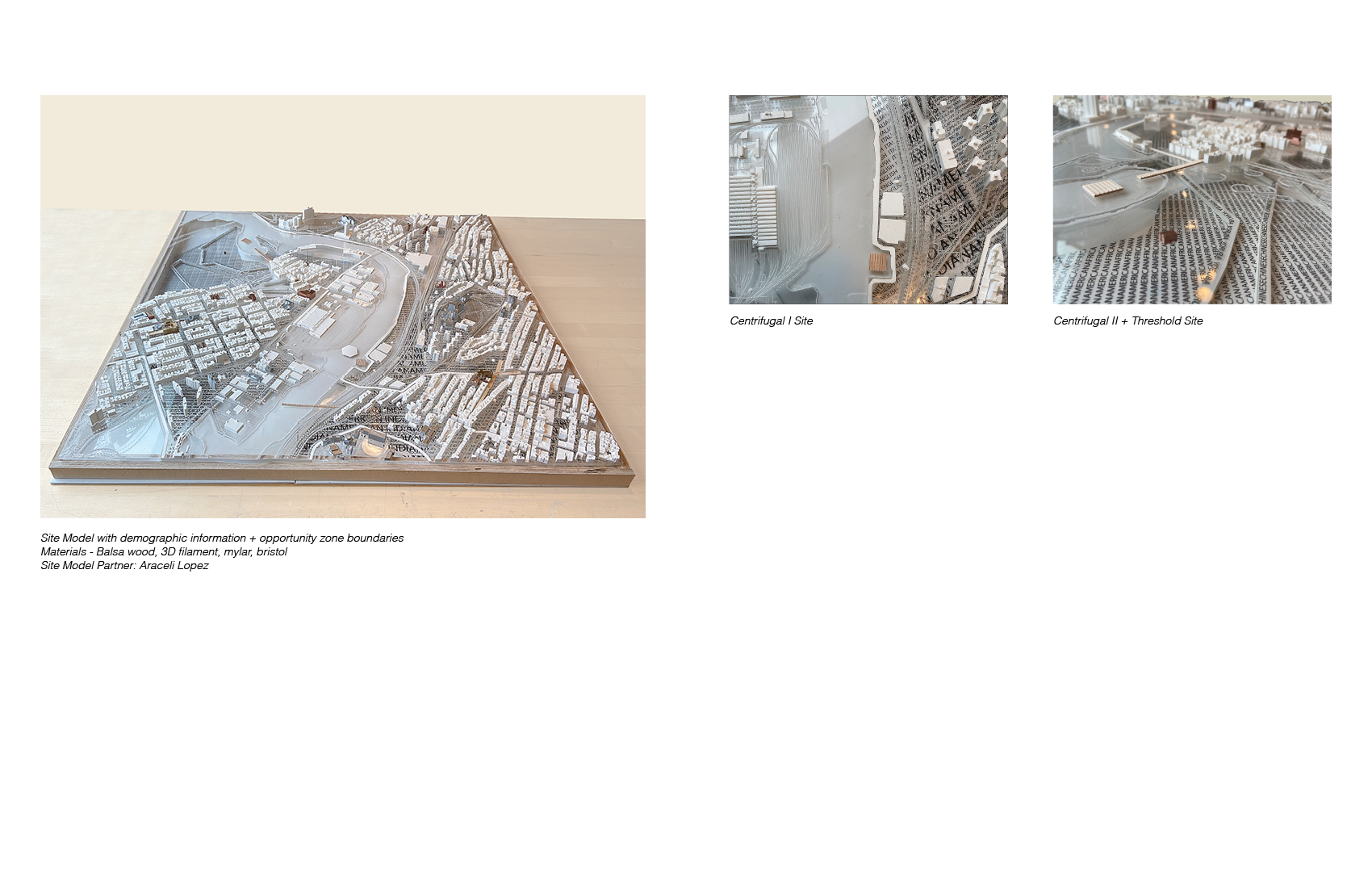

CITY, RENEWED

The Nature Culture Nexus Plan

New York, NY + Bronx, NY

Urban Design Studio IV

Critic: Bimal Mendis

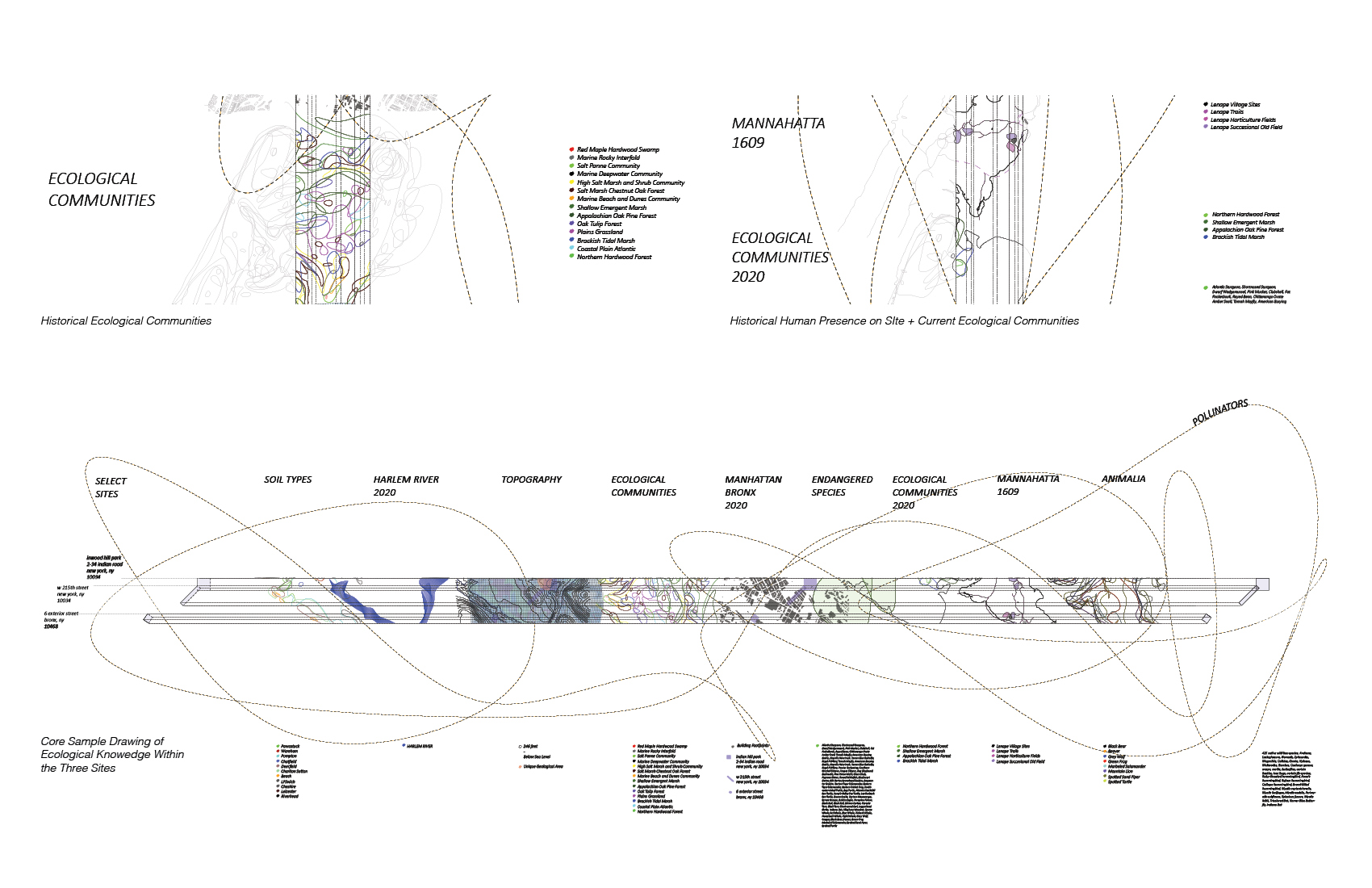

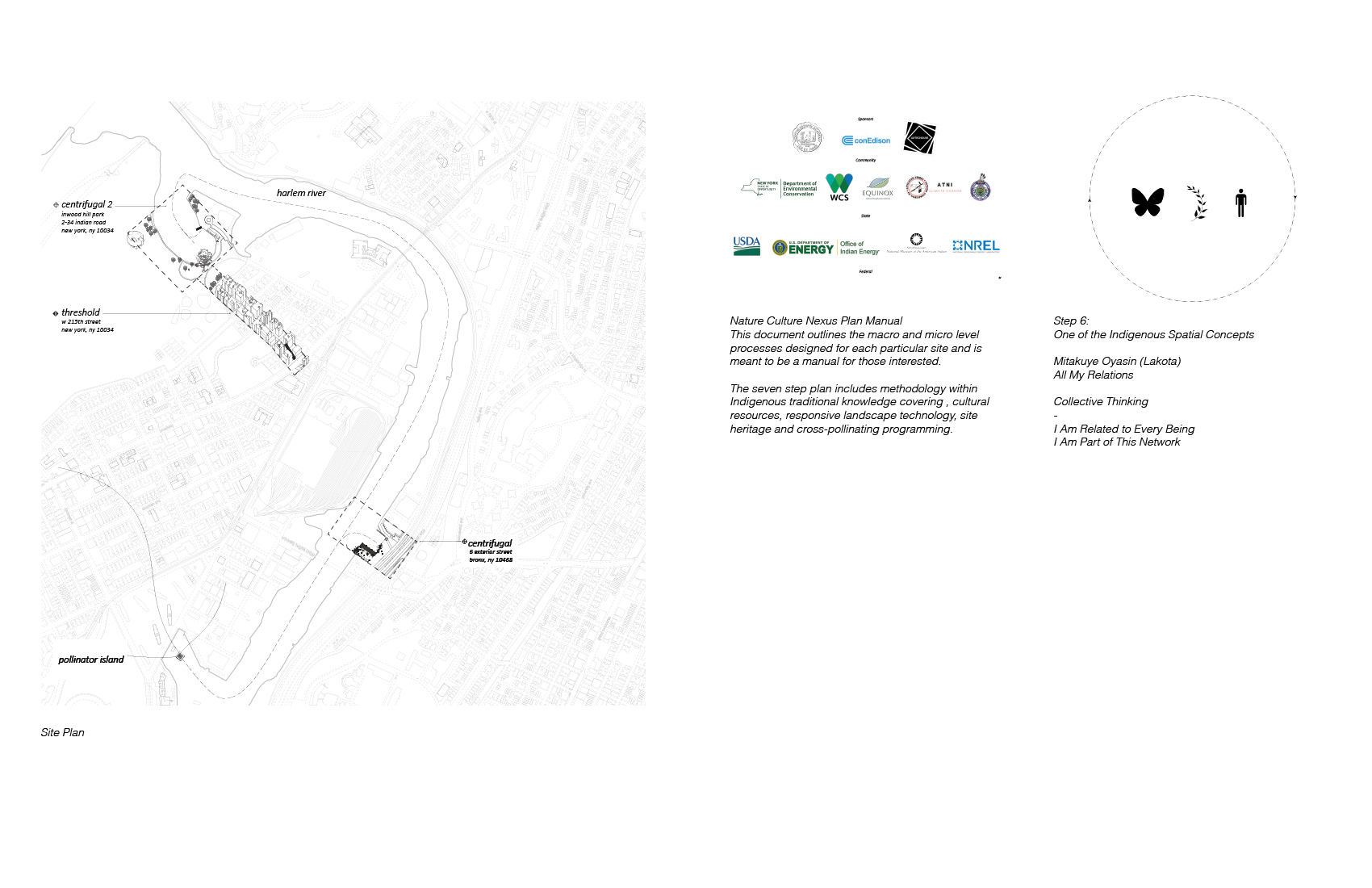

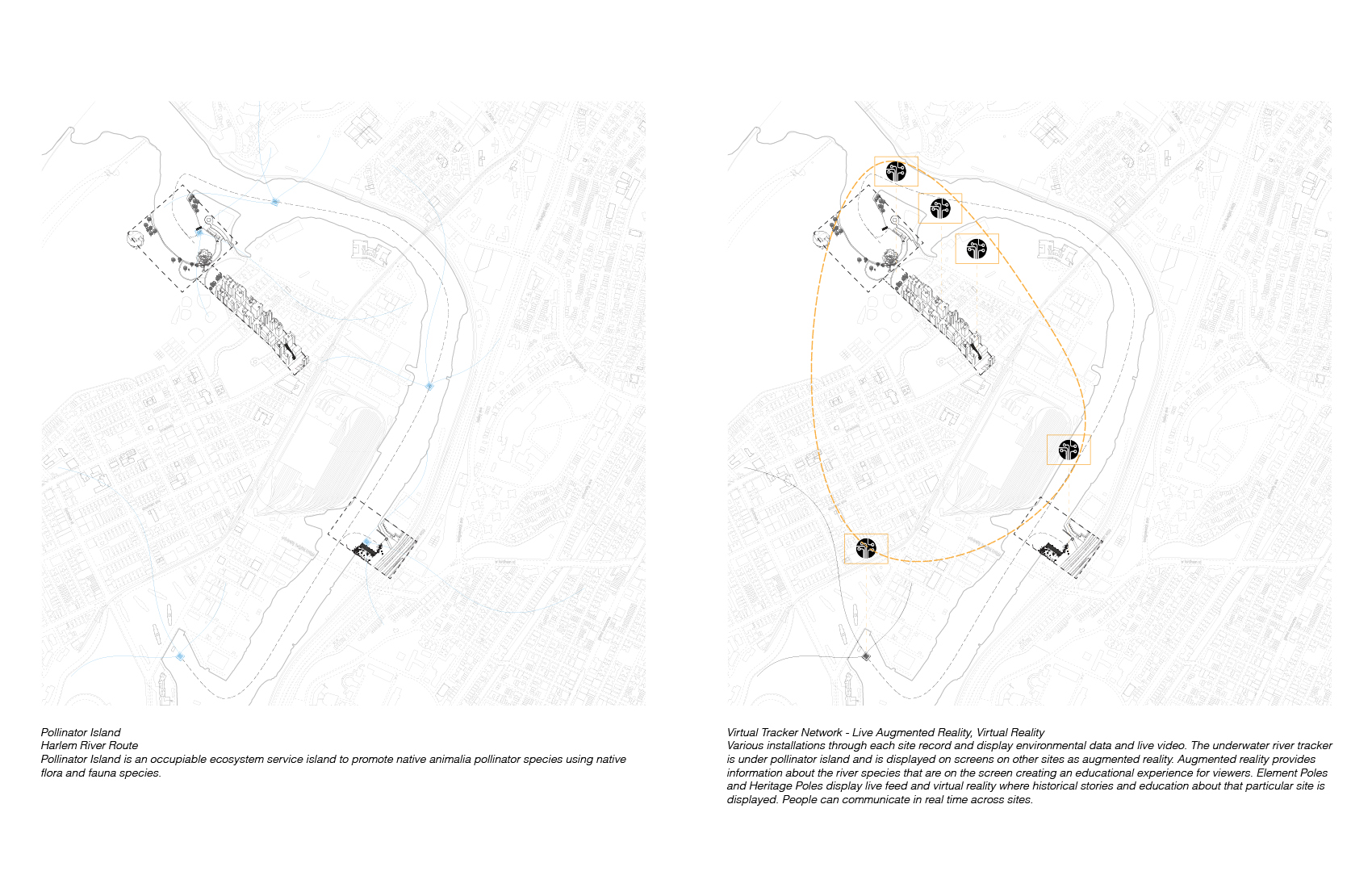

The dependency humans have on the ecological environment has been ubiquitous for time immemorial and yet many natural processes are unacknowledged and often directly contradicted by human activities. The loss of ecological consciousness is an urban crisis and stems from the coupled erasure of ecological knowledge and forced displacement of the communities who know these environments thoroughly; the Indigenous communities.

The Nature-Culture Nexus Plan restores the Indigenous knowledge and practices of historical ecological consciousness of Inwood, Manhattan and Fordham Landing, Bronx by revealing the unseen interdependencies with the natural world recharging the reciprocal relationship between the collective of people, animals, plants, fungi and ecosystems, ultimately reengaging the built environment with the natural environment. The plan is designed to be a framework to sow across both ecosystems and urban places, while recognizing and strengthening the unique histories and current conditions of each site. The plan is carefully complementary to sustainable policy including the Green New Deal and the Pollinator Protection Plan of New York State. Weaving community, state and federal partners and programs strengthens the collective and provides new knowledge and application. The seven step plan includes methodology within Indigenous traditional knowledge covering, cultural resources, responsive landscape technology, site heritage and cross-pollinating programming.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

PRODUCTIVE UNCERTAINTY: INDETERMINANCY, IMPERMANENCE AND THE ARCHITECTURAL IMAGINATION

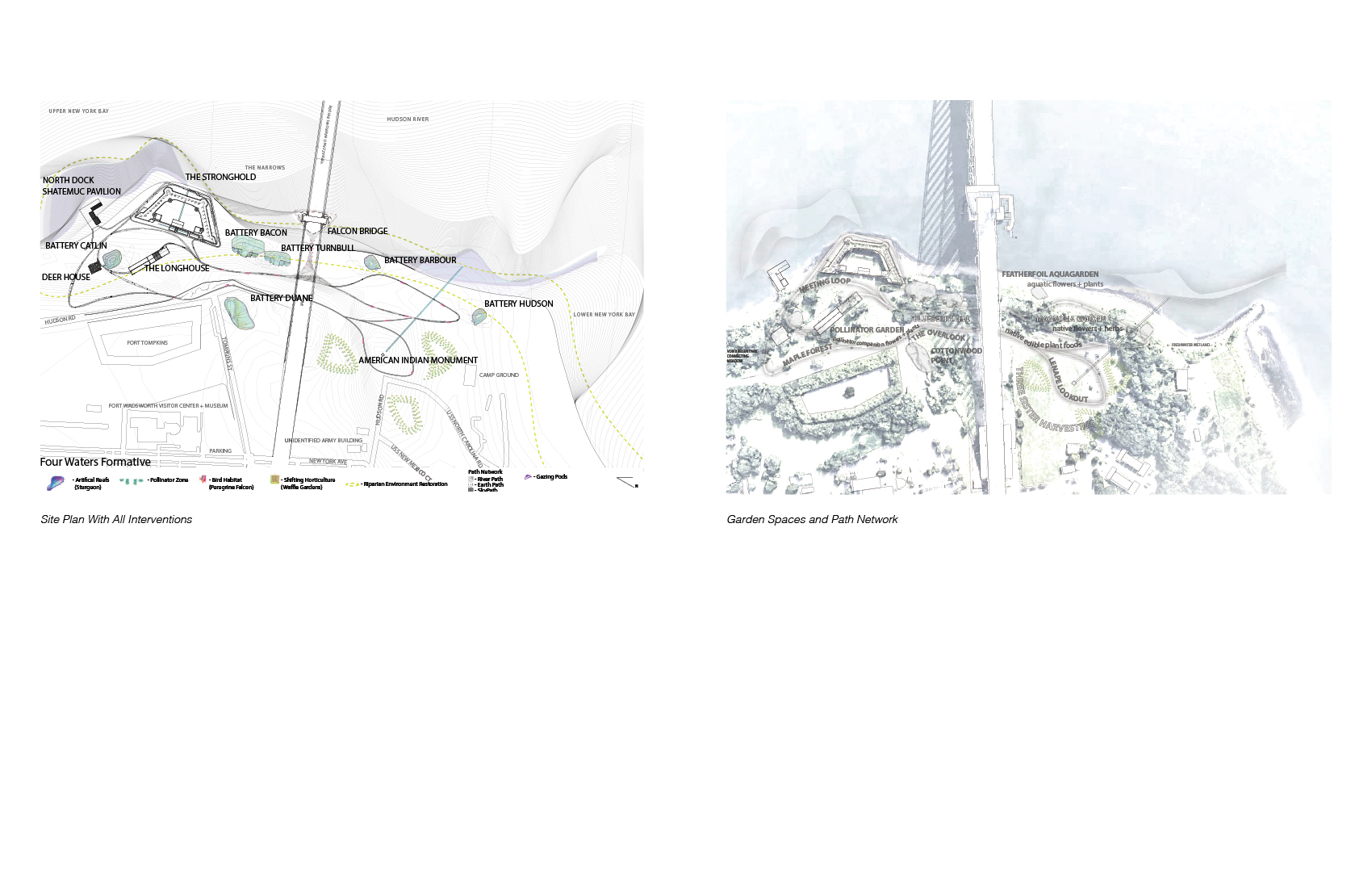

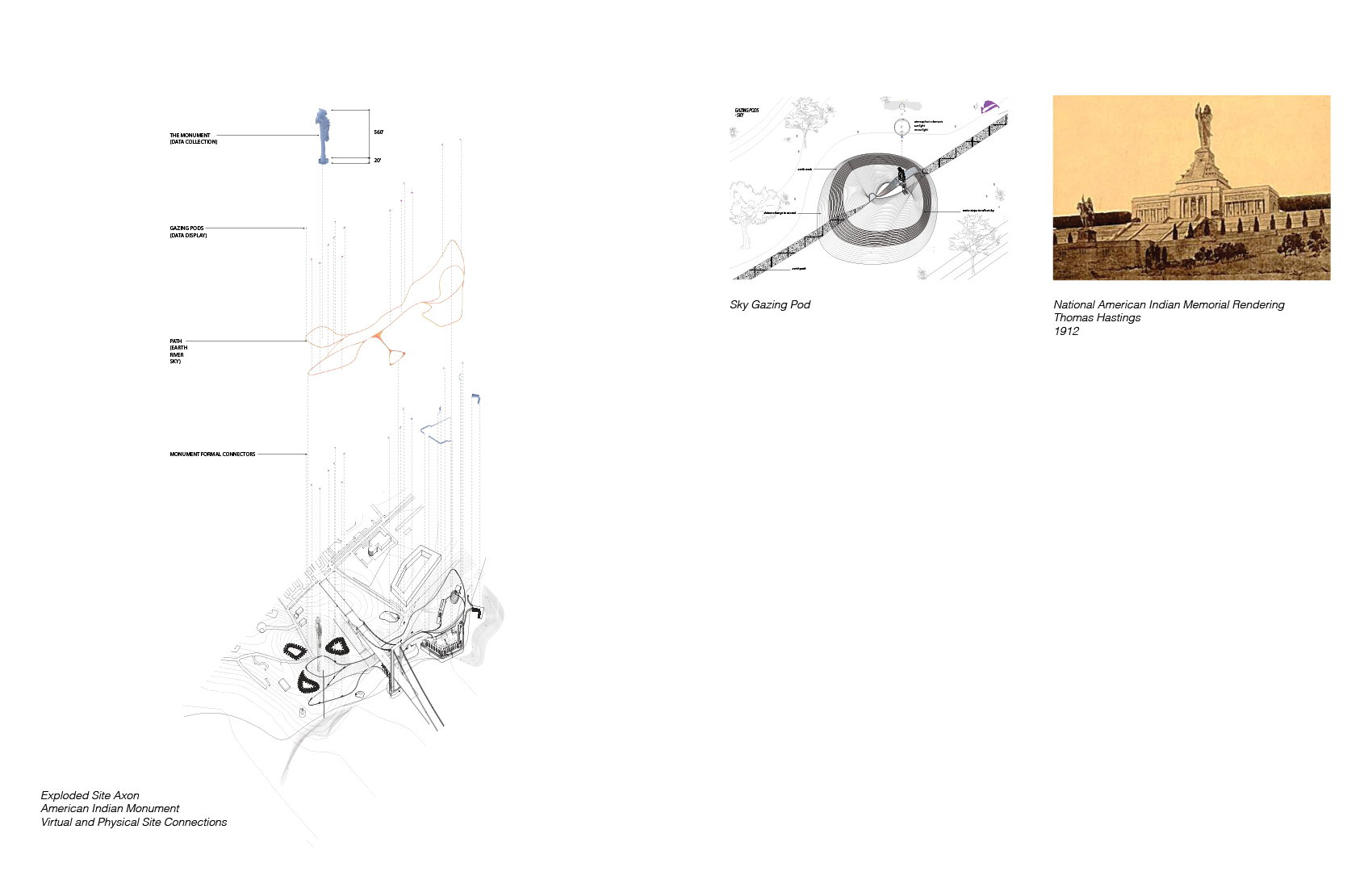

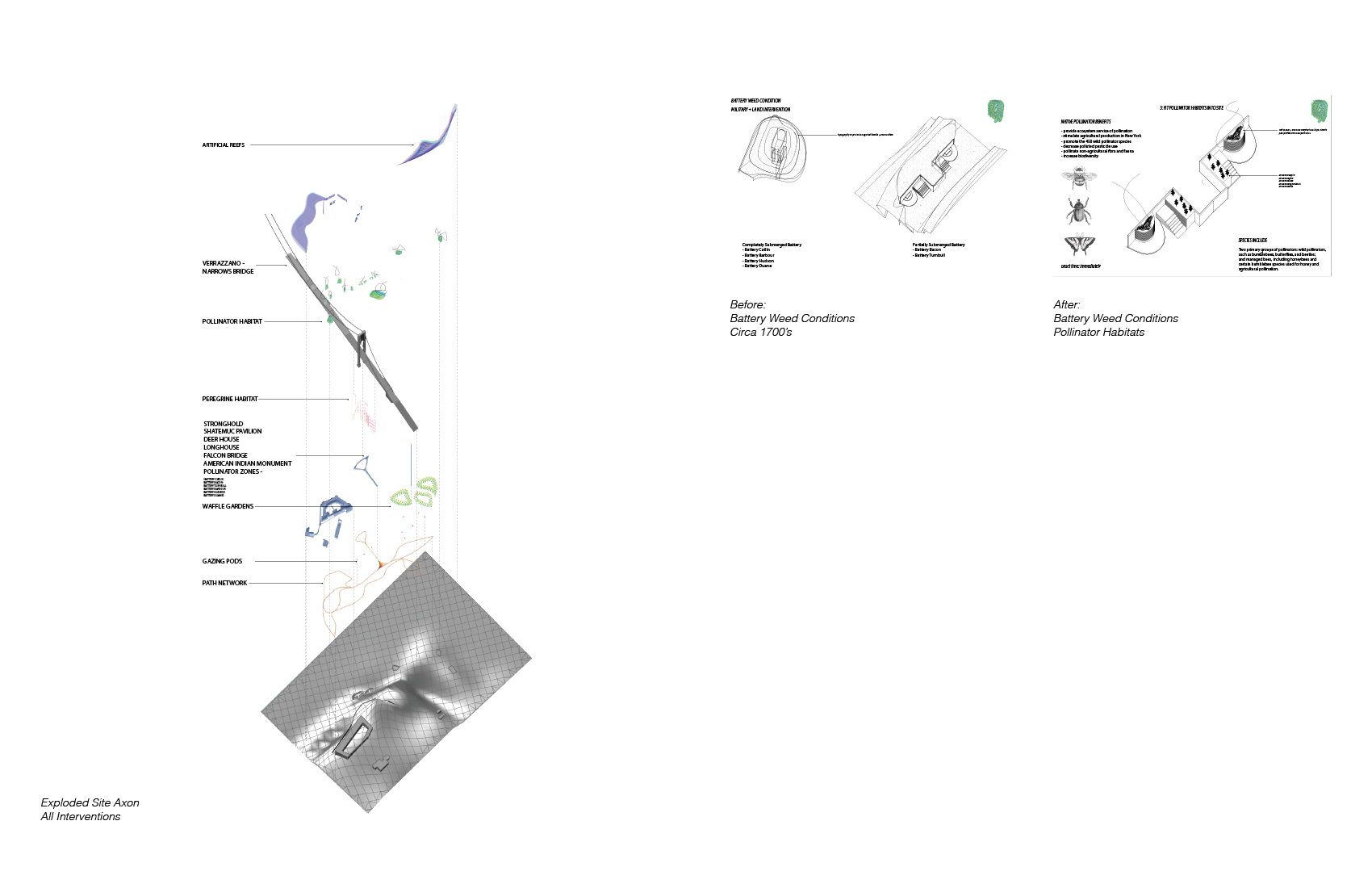

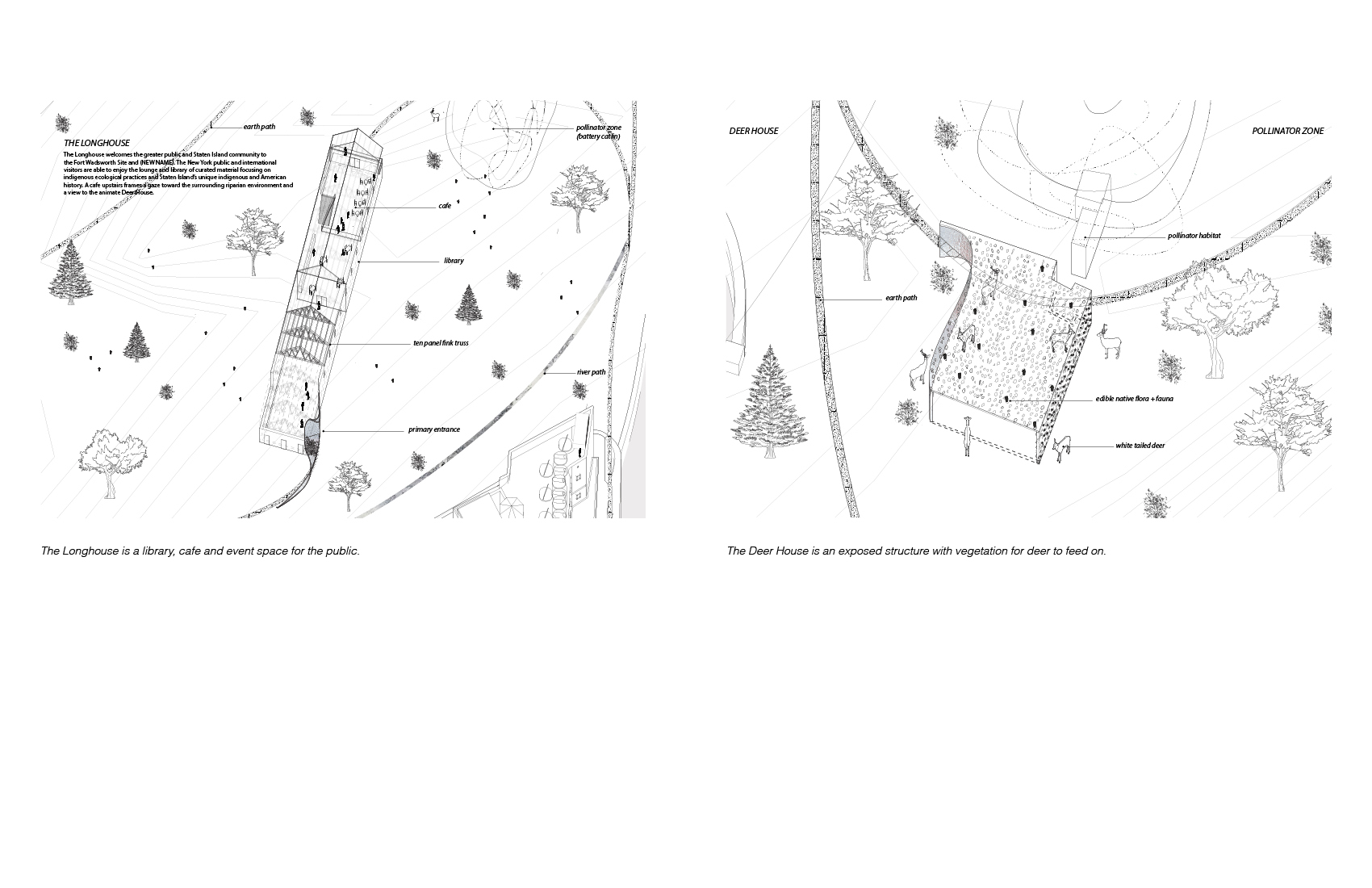

Four Waters Formative: A Living Laboratory

Staten Island, NY

Advanced Design Studio V

Critic: Marc Tsurumaki, Violette de la Selle

The fundamental paradox of uncertainty for a discipline based on projection, of impermanence for a practice predicated on permanence, defined the studio. The studio proposed how the material conditions of architecture might engage with the increasing volatility that characterizes our collective relationship to emergent environmental, climatological, biological, political and social conditions.

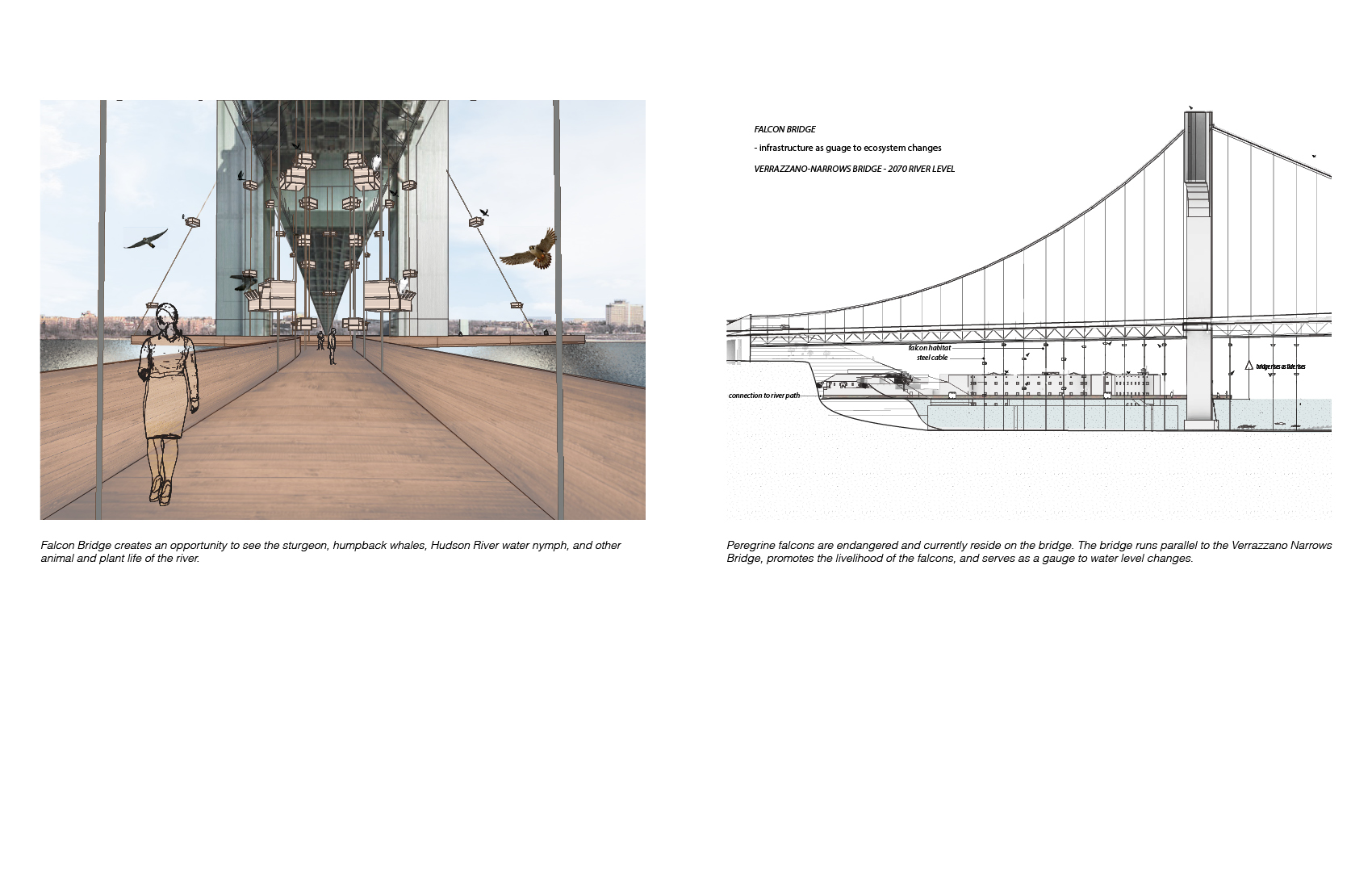

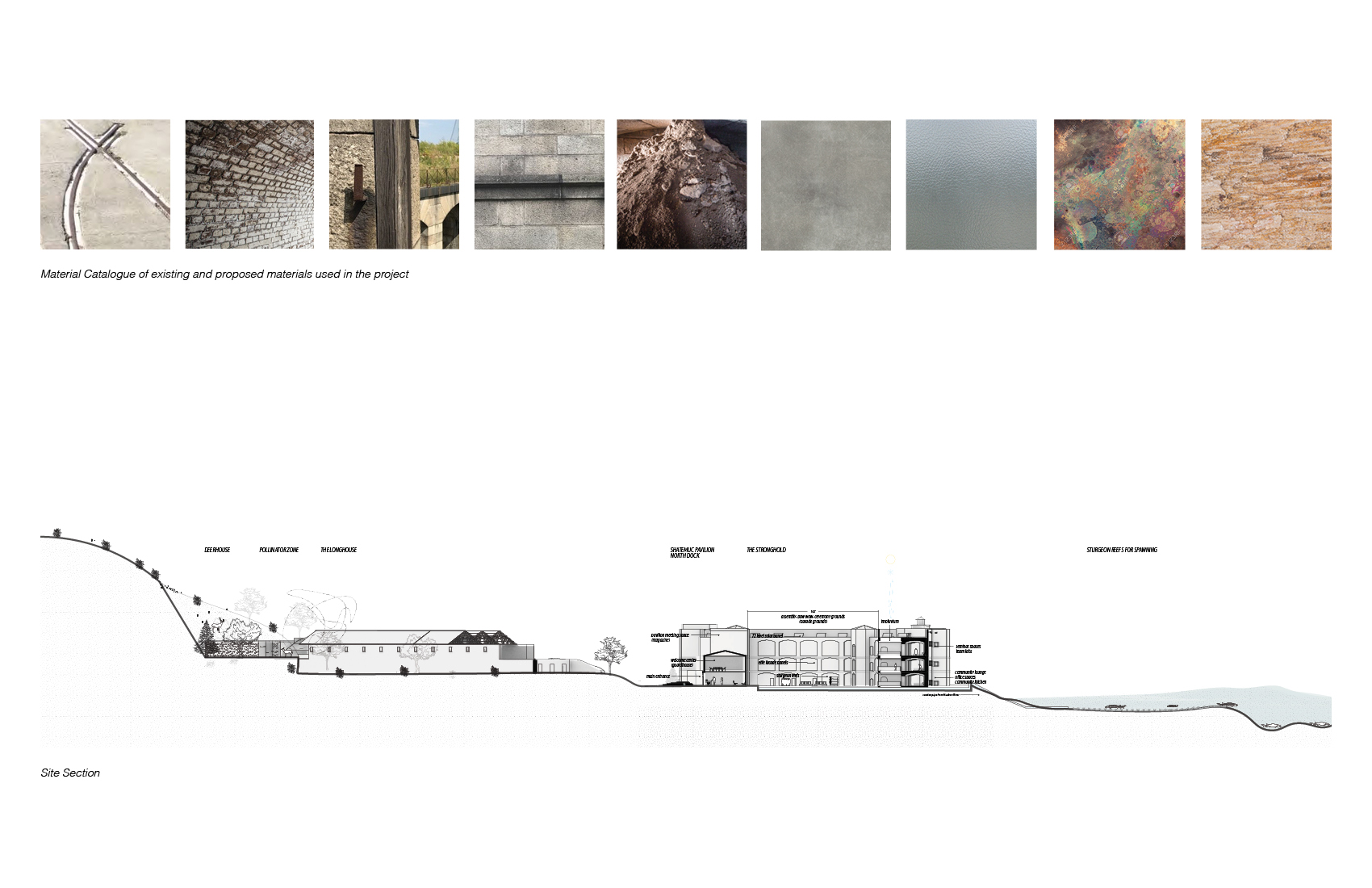

Four Waters Formative is a Living Laboratory for Indigenous ecological knowledge integrating adaptive design, land remediation and historical preservation. Fort Wadsworth (renamed Four Waters Formative) is on Staten Island and is part of the Gateway National Recreation Area as a National Park and is considered federal land. Four Waters Formative acts as a reinterpreted National Park and histrocially preserved military site, with on site education and a place to promote collaboration between the greater public, tribes and federal programs. The program centers around the the Stronghold as a gathering place while the path system weaves together interventions including gazing pods, artificial reefs, pollinator batteries, earth work, Shatemuc Pavilion, the Deer House, the Longhouse, Falcon Bridge and the American Indian Monument; a data collector and visual indicator of live environmental information. Membrane as a means of perception, the gaze, and fortification and various indigenous design principles were explored throughout the project.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

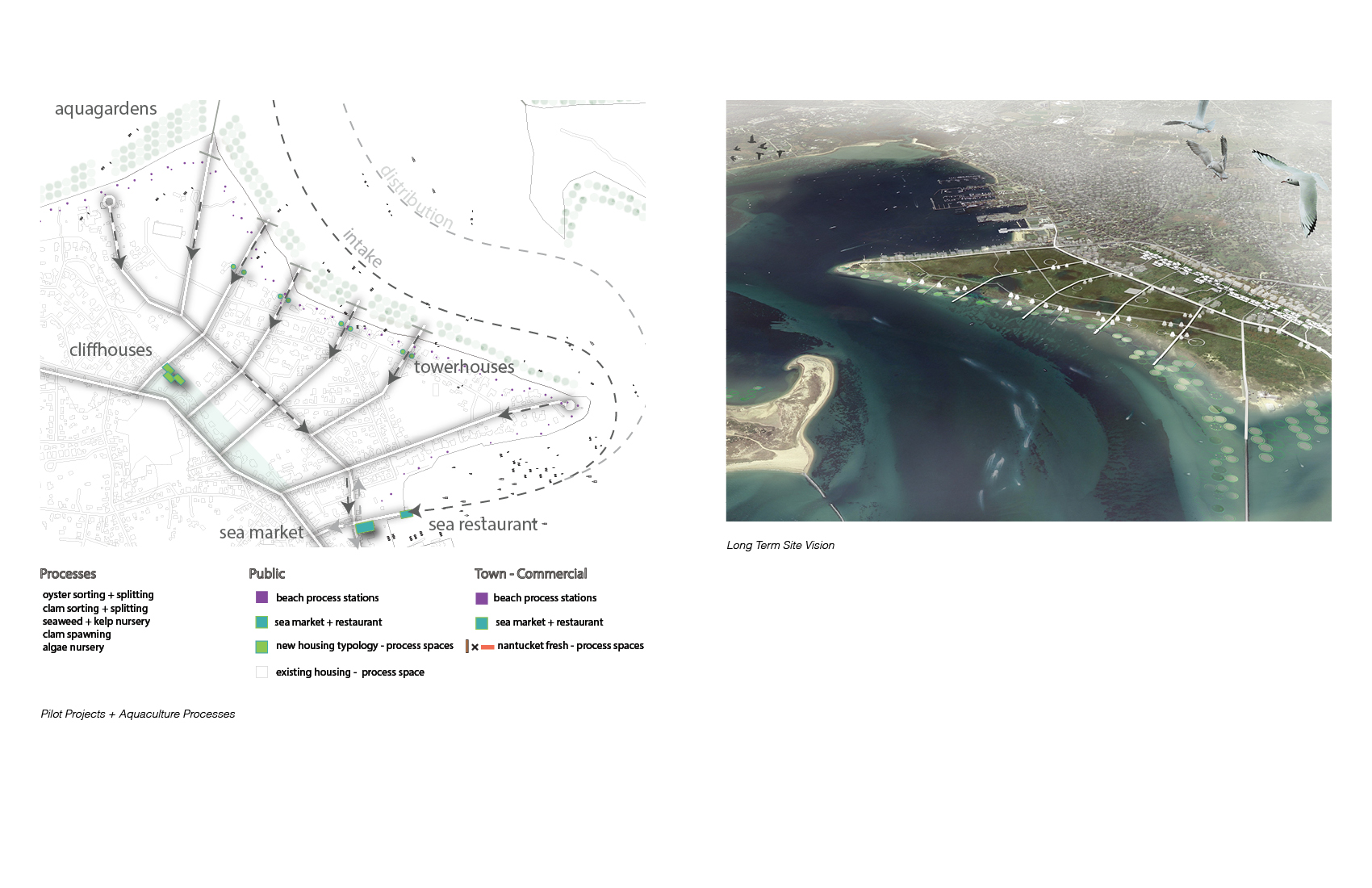

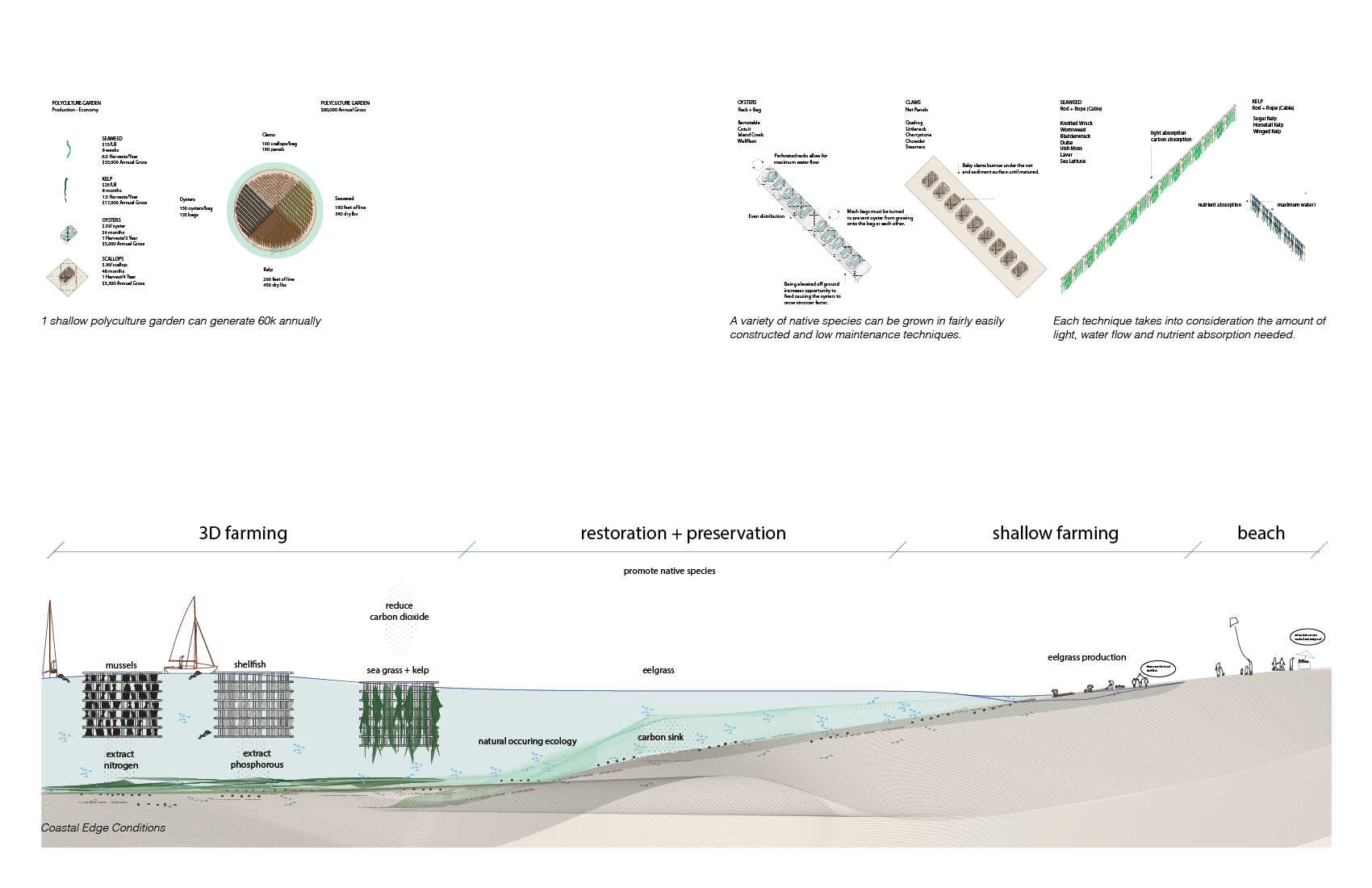

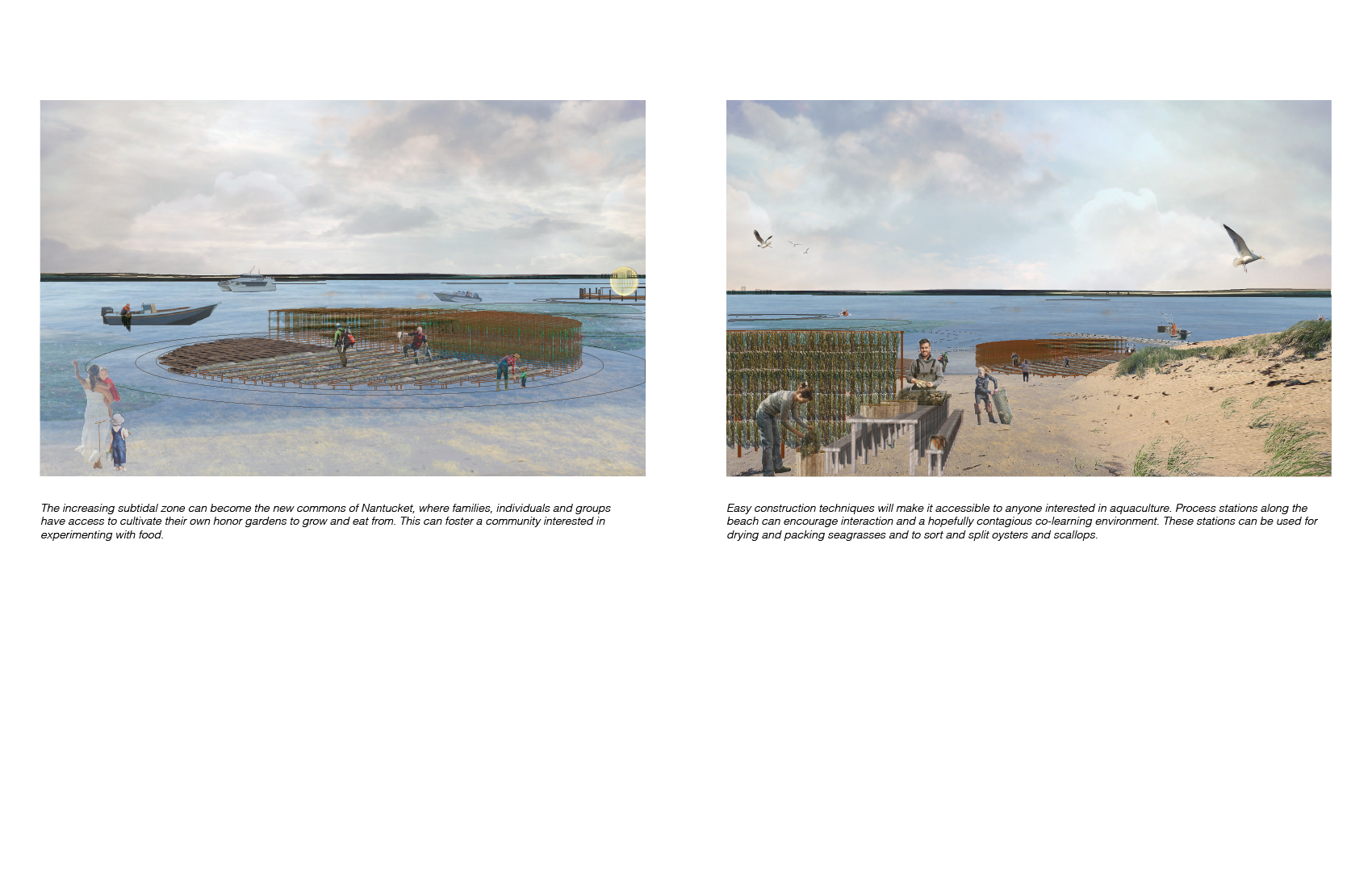

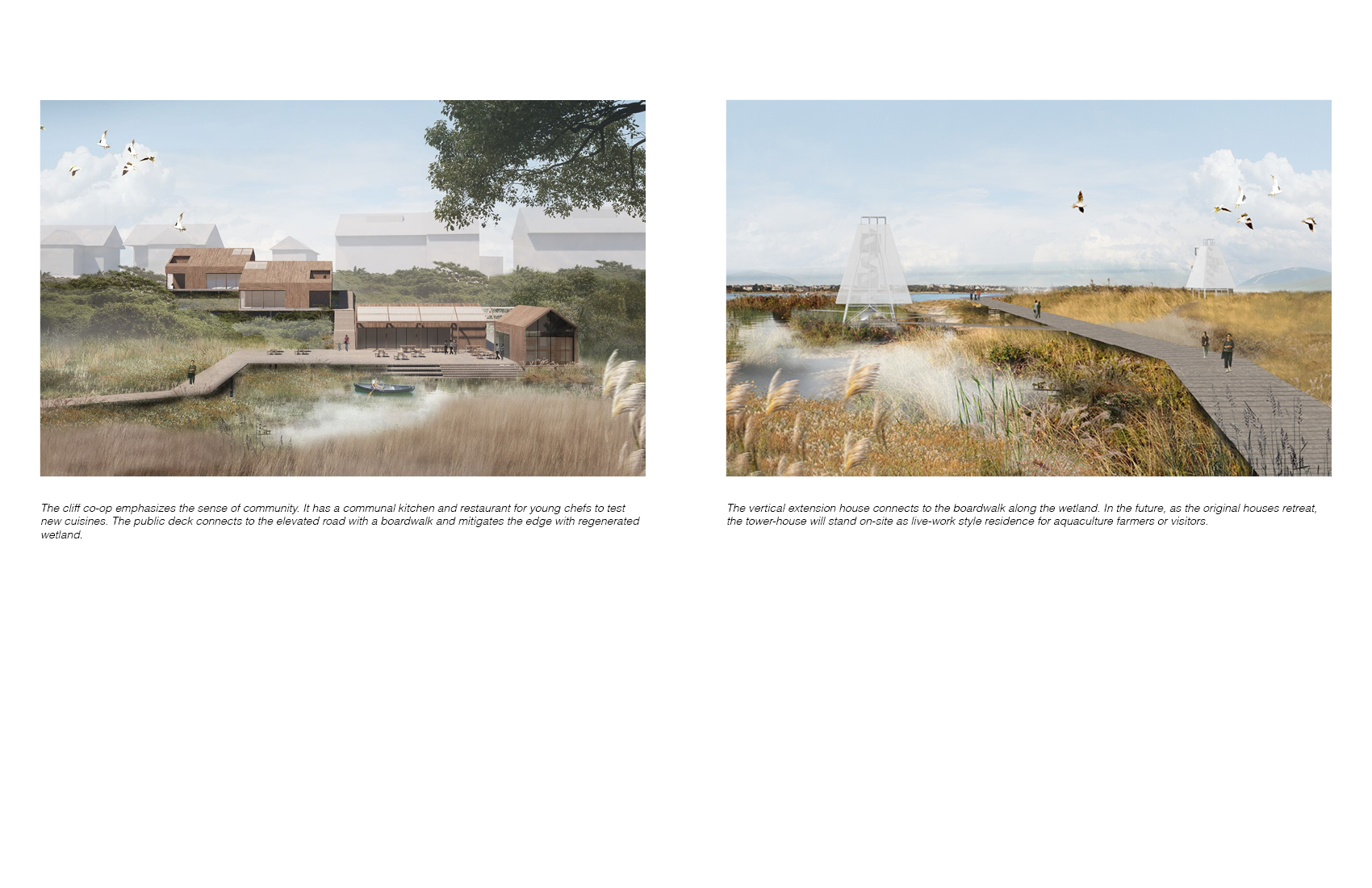

COASTAL NEW ENGLAND: HISTORY, THREAT AND ADAPTATION

New England Foodways: Reconnecting Nantucket with Traditional Cultures of Water, Land and Food

Nantucket, MA

Advanced Design Studio VI

Critic: Allan Plattus, Andrei Harwell

Team: Anjelica Gallegos, Daoru Wang, Robin Yang

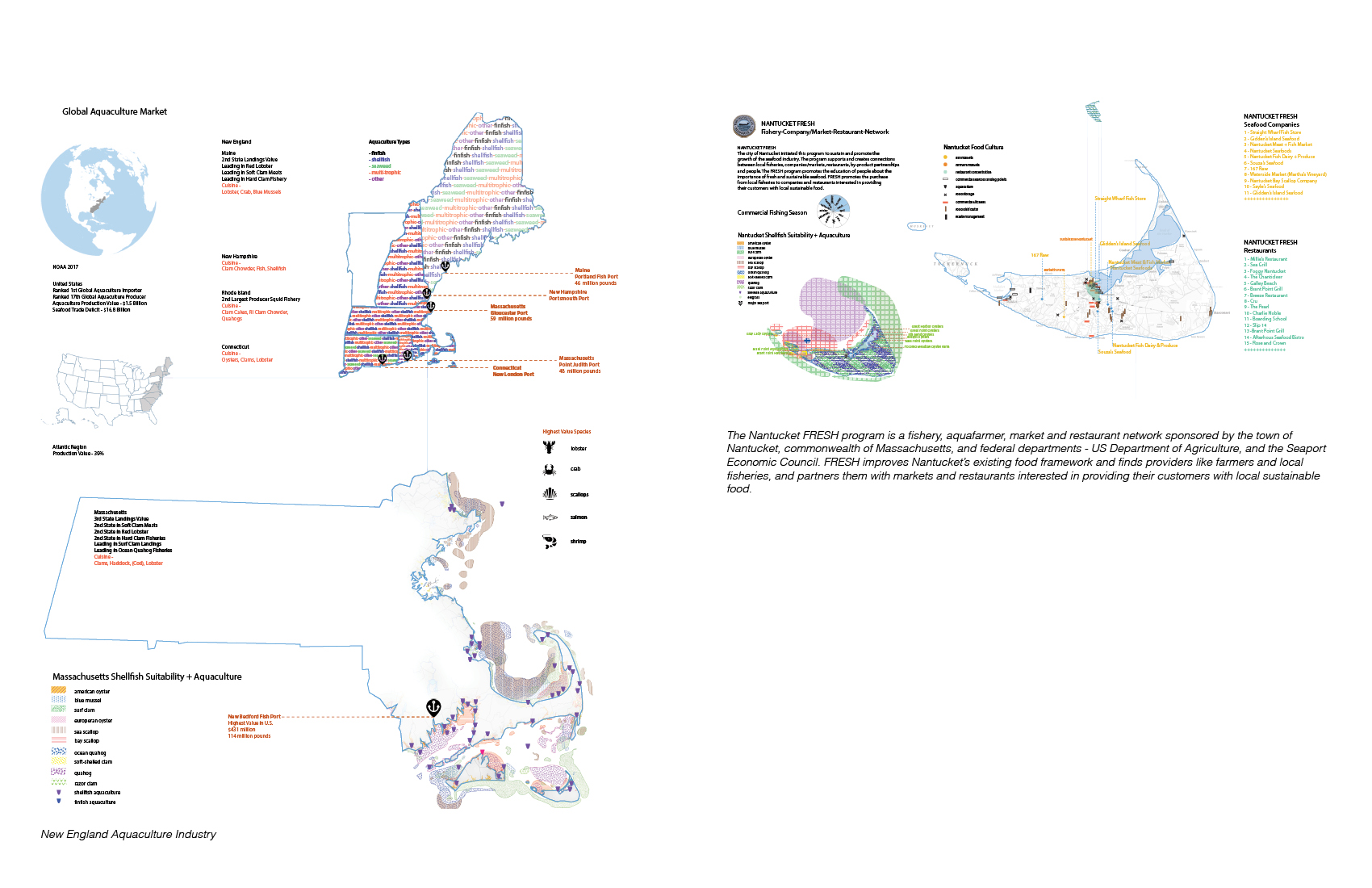

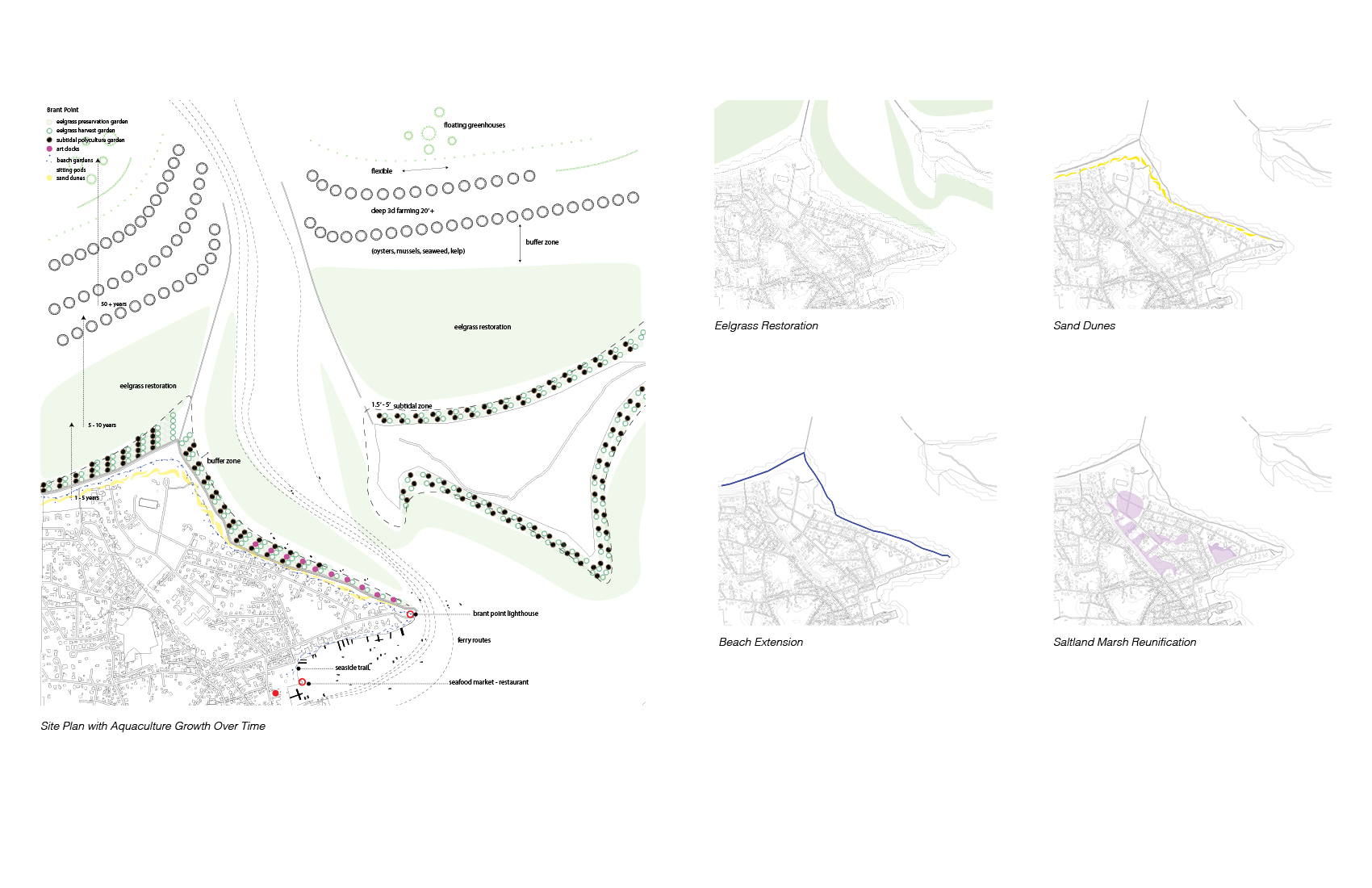

Along with four other universities, Yale School of Architecture, was invited by ReMain Nantucket, an island-based non-profit, to participate in a collaborative studio exploring design approaches to wide-ranging challenges of coastal resilience and adaptation, cultural heritage, and environmental justice. This studio will consider broadly the natural and human landscape of coastal New England, with a specific focus on the island of Nantucket and related coastal sites.

Our project has three main focus areas including adaptation, rebalance, and the regional food network. From the indigenous peoples, to the maritime quakers, the spirit of Nantucket has been to embrace challenges and recognize potential. We propose a new circular economy centered around aquaculture. Responding to sea level rise, flooding, and coastal erosion, we use modes of regeneration, mitigation, and migration to focus on incremental adaptation.

Allowing and strengthening the natural infrastructure to fully function creates reciprocity, is economically wise, and has concrete benefits. We introduce a range of dynamic landforms to mitigate rising waters at different time periods, including extending the beach, introducing sand dunes, and restoring eelgrass beds. The main artery of the raised infrastructure will be Beach Street, where a series of boardwalks will reach to the harbor edges of Brant Point.

Nantucket is part of the second largest United States aquaculture producing region and is part of New England’s network of diverse aquaculture. The increasing subtidal zone along Brant Point can become the new commons of Nantucket, where people have access to cultivate their own aqua gardens to grow and eat from. A sea market and processing center will invite the public to taste Nantucket’s unique foods and show different processing techniques. As the tides rise, two new housing types: the tower-house and cliff co-op will be introduced. Brant Point can lead the growing shift toward regenerating community connection with the land, eating from sources closer to the region, and evolving balanced maritime living.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

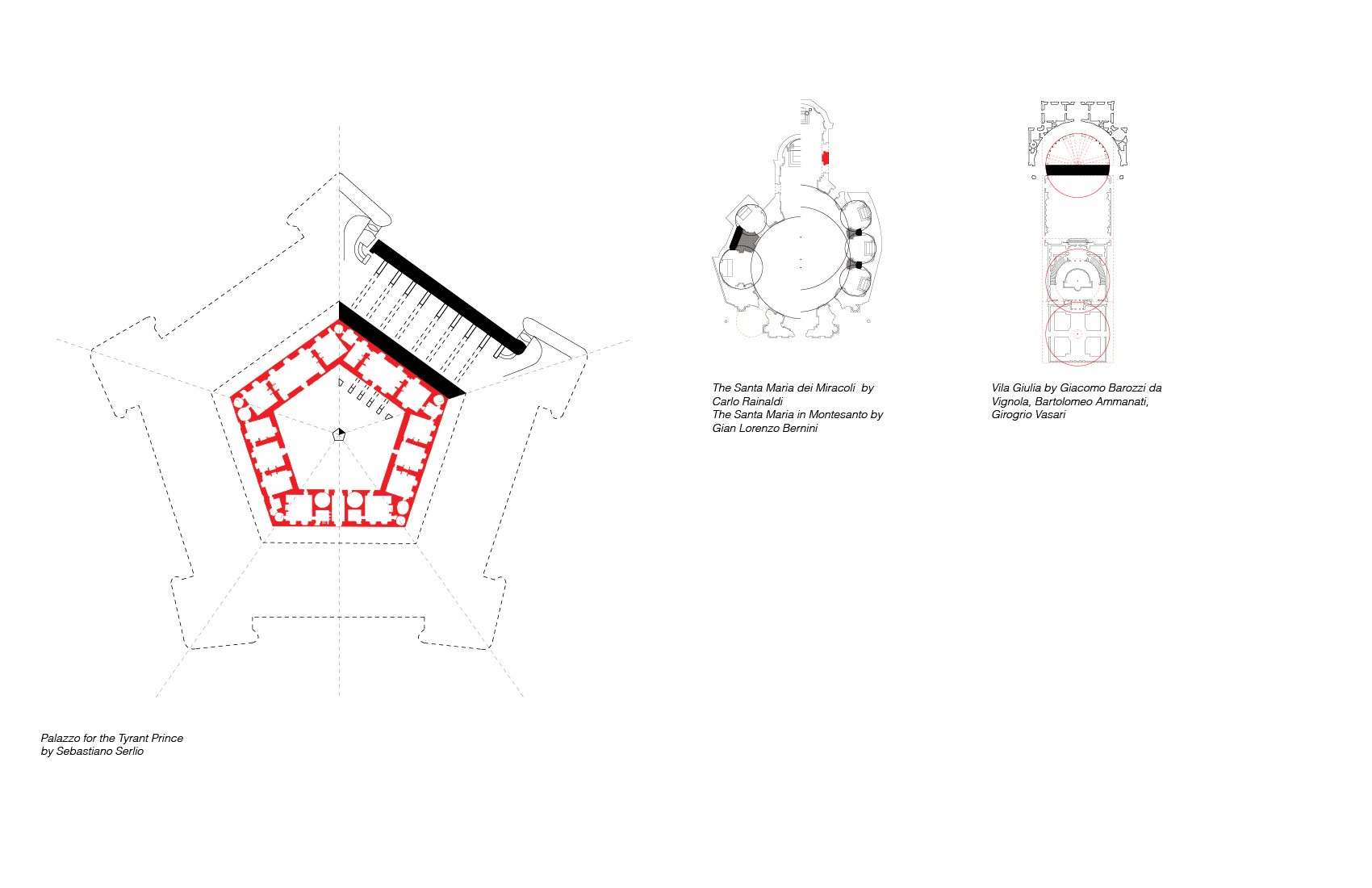

FORMAL ANALYSIS

Critic: Peter Eisenman

Learning to see and read as an architect was inititated through this course as a series of weekly texts and analyses that move from the theocentric late - medieval, to the humanism and anthropocentricty of the early Renaissance, to the beginning of the Enlightenment of the late eighteenth century. Based on the texts an argument was constructed about the spaces and shown through drawing.

![]()

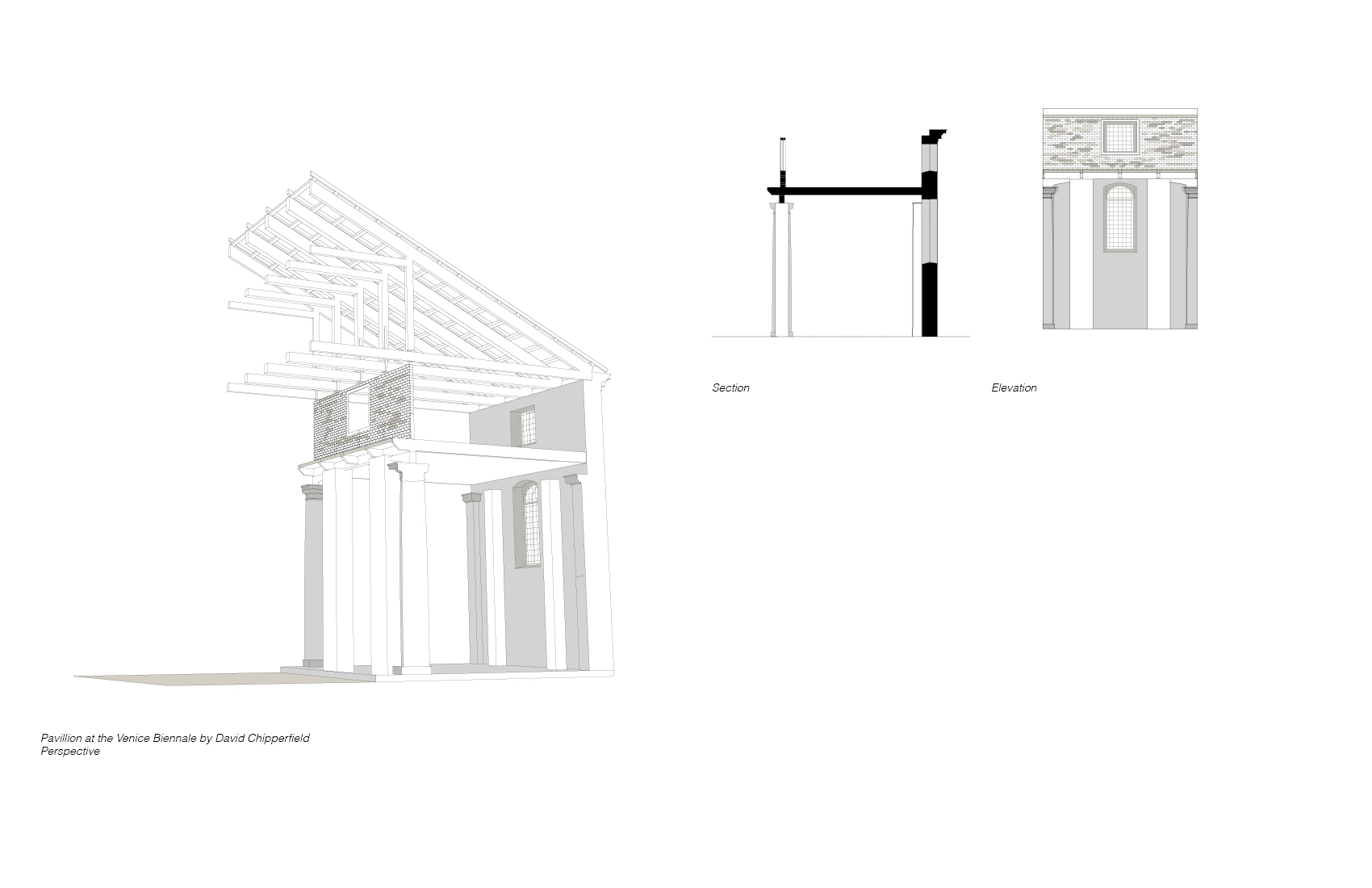

AFTER THE MODERN MOVEMENT

Critic: Robert A. M. Stern

This course aimed to answer the questions, What was and What is postmodernism in architecture? Postmodernism should not be seen as a style, but rather as a condition reacting to the ahistorical, acontextual, self-referential materialism that orthodox modernism had come to represent in the post–World War II era.

Students are conceptualized and design a facade in the manner of a chosen architect for an alternative Strada Novissima. In the design of the facade, students adhered to the same brief given to the Strada Novissima participants in the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale.

According to David Chipperfield, we must maintain the identity of places. The preservation of history tells a society who they are today. Individual buildings do not encapsulate a society’s character or the character of a place themselves, rather the collected composition of buildings and the connecting streets weave the urban fabric together in an influential timeline where the past influences the present. I treated the given elements as a historical structure which needed a level of protection and restoration. Therefore, I preserved the four existing columns, original identified grid and visual access to the windows. I consider the current social dynamic of the street as an important context for the facade to have a conversation with, allowing circulation from the street to enter the exhibition area through the columns. I respected the current grid system and restored two columns which used to be there. Additionally, I restored the facade. The intention was not to replicate the past facade but rather allow its presence to be felt and respected by using harmonizing foundational forms and materials of similar hued marble and recycled handmade brick. The heritage of the facade is preserved and protected while presented in unison with a concurrent architectural identity.

![]()

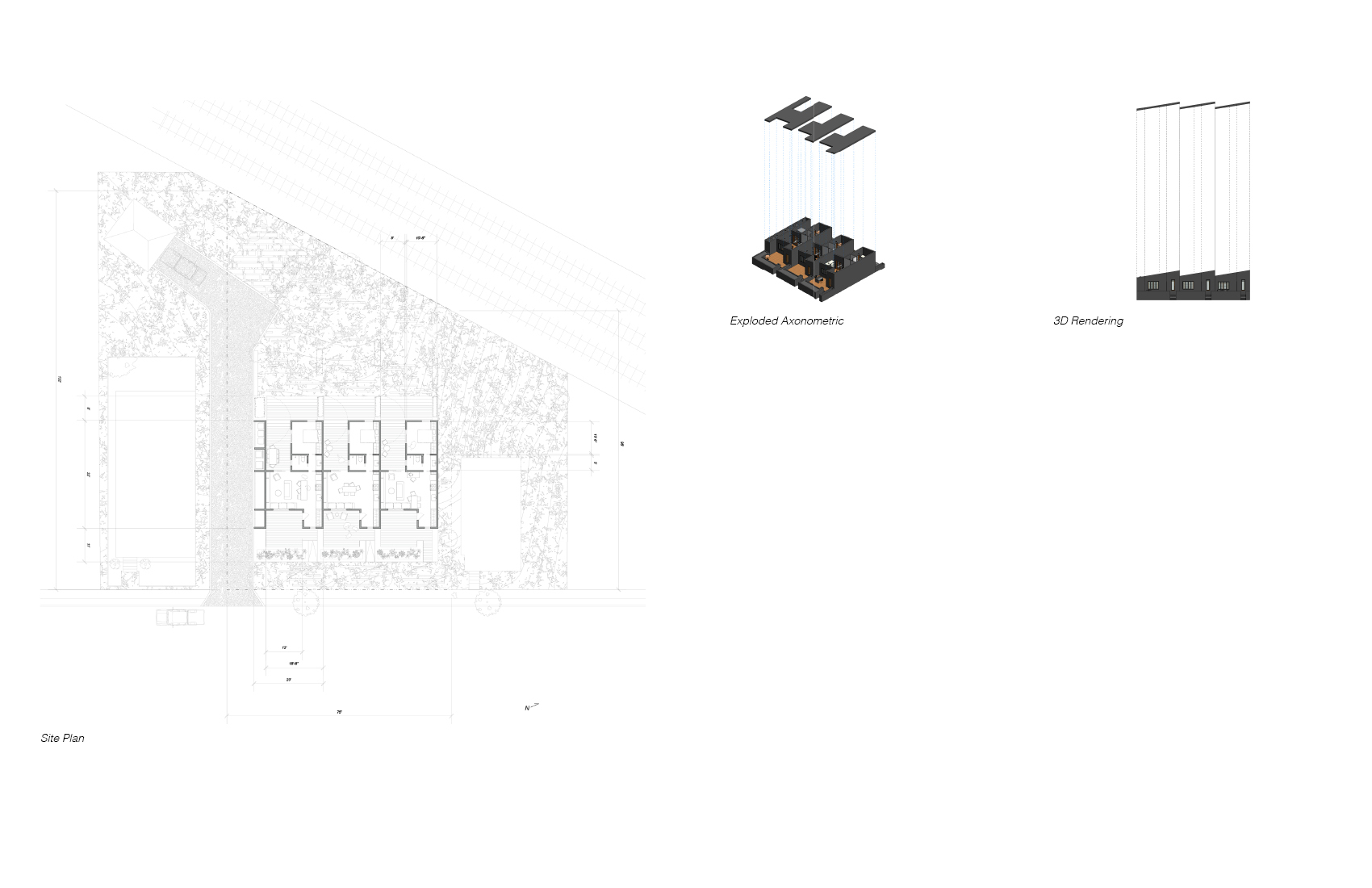

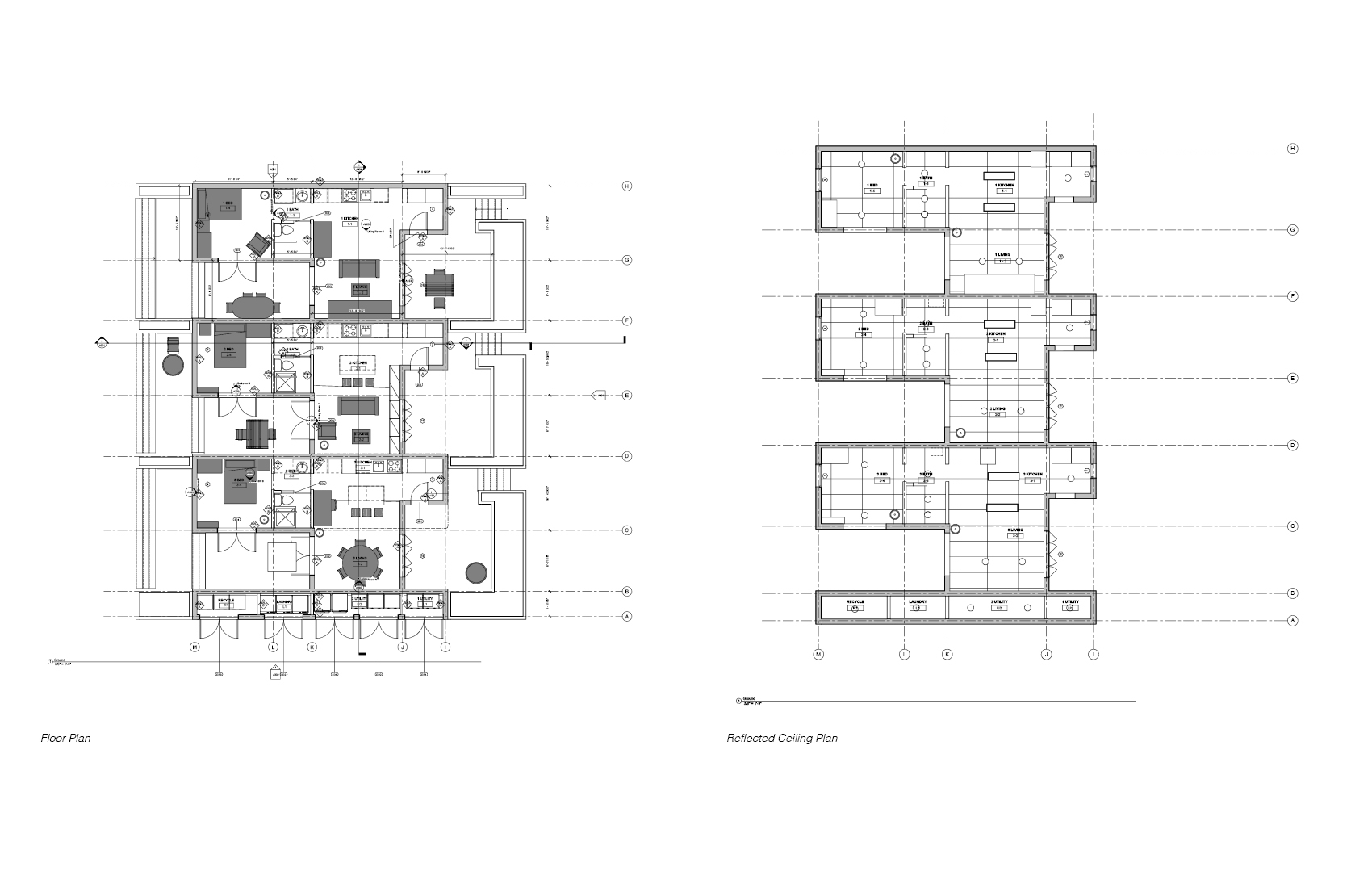

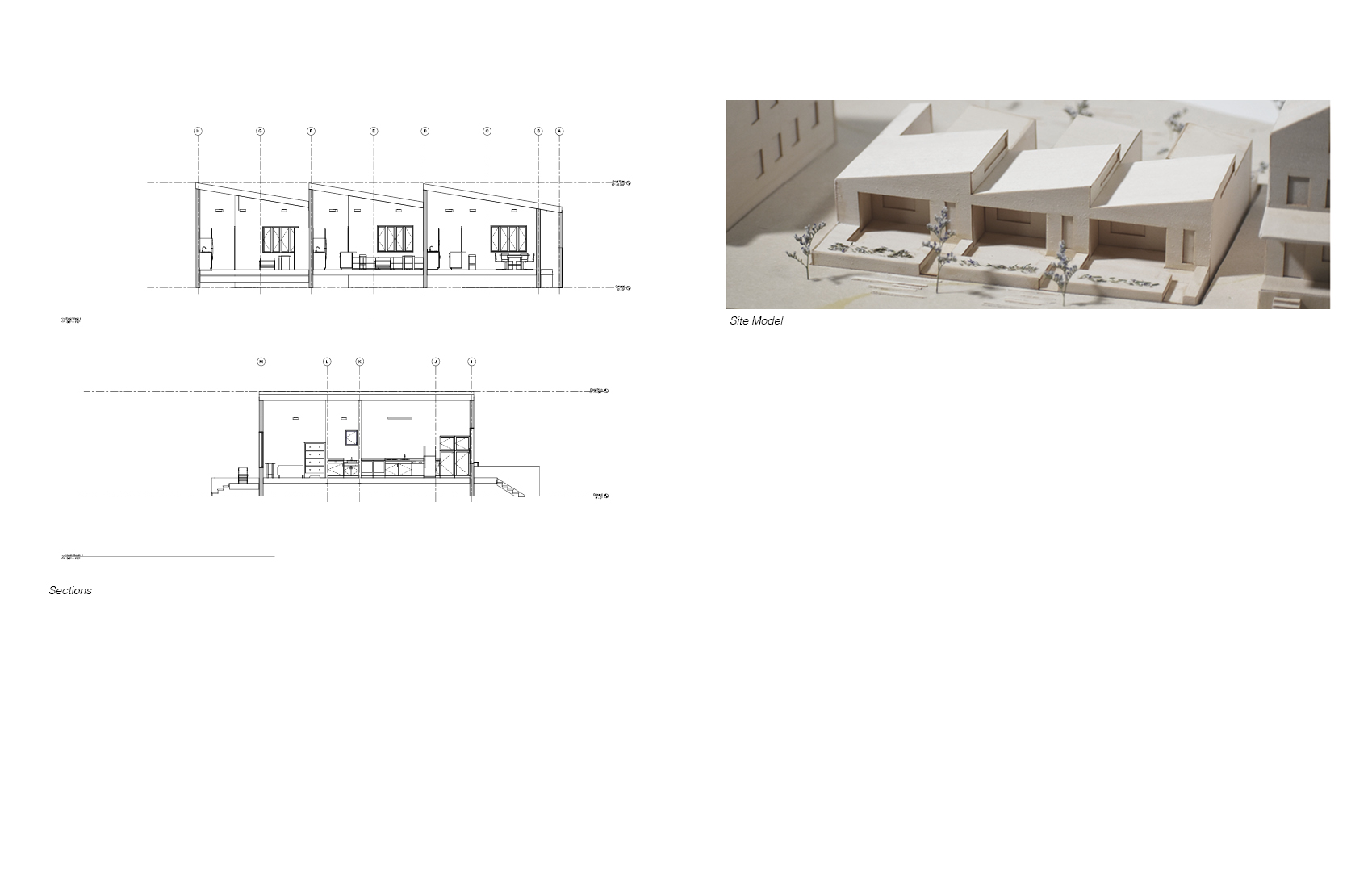

JIM VLOCK BUILDING PROJECT -

BUILDING INFORMATION MODELING

Critic: Alan Organschi , Julie Zink

Team: Anjelica Gallegos, Kevin Gao, Ashton Harrell, Niema Jafari, Leanne Nagata

The Yale Building Project of 2019 collaborated with the Columbus House of New Haven to articulte and design 3 units for previously homeless individuals. 1300 sq ft apartments were designed to include living, bedroom, bathroom, kitchen and shared mechanical systems, waste, recycle and outdoor garden space. The class focused on garnering a deep understanding and skill level with BIM platform Revit. The management of work flows and model integrity while understanding the interrelationships of working on a virtual live model with other designers was paramount.

![]()

![]()

![]()

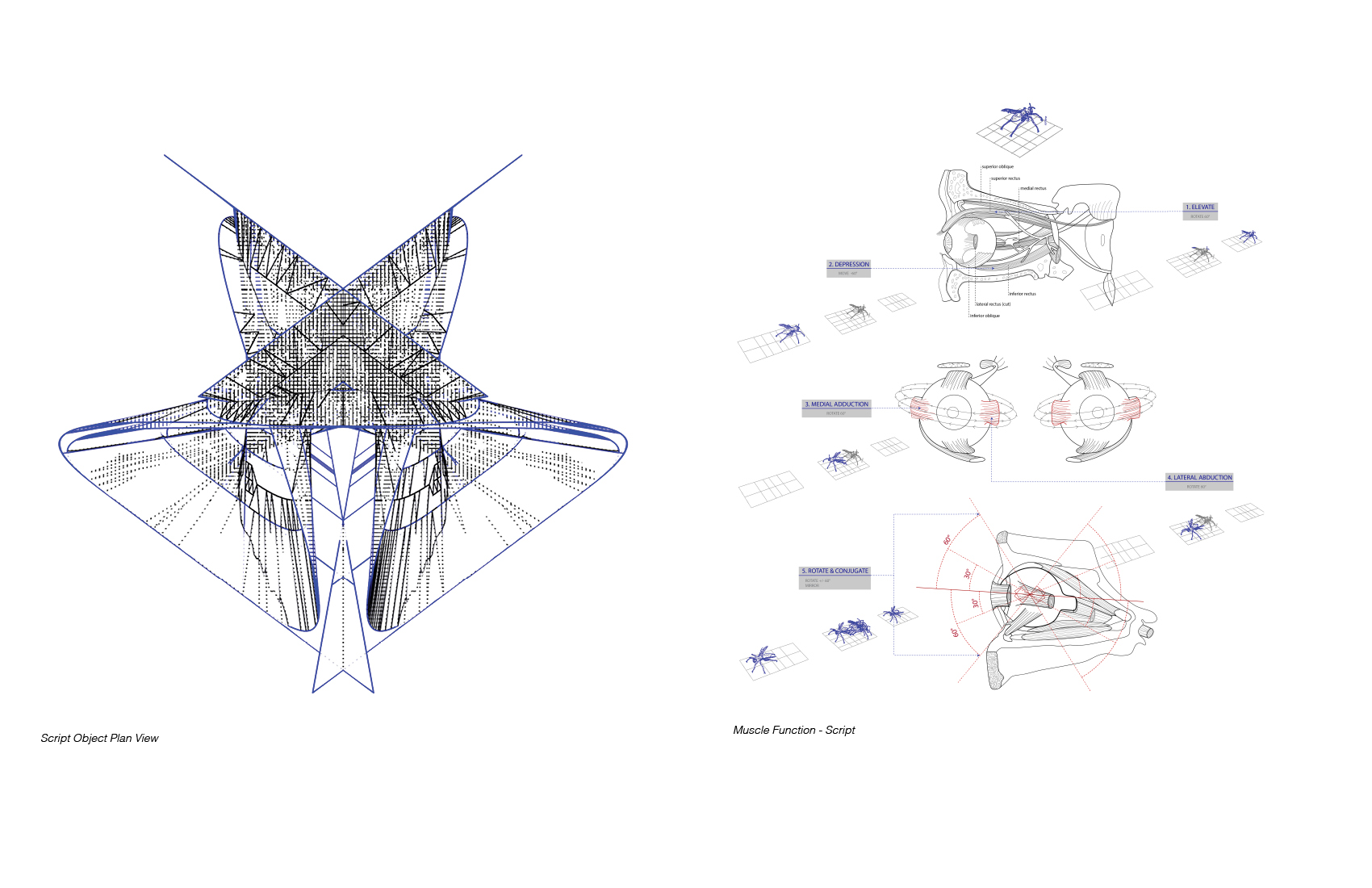

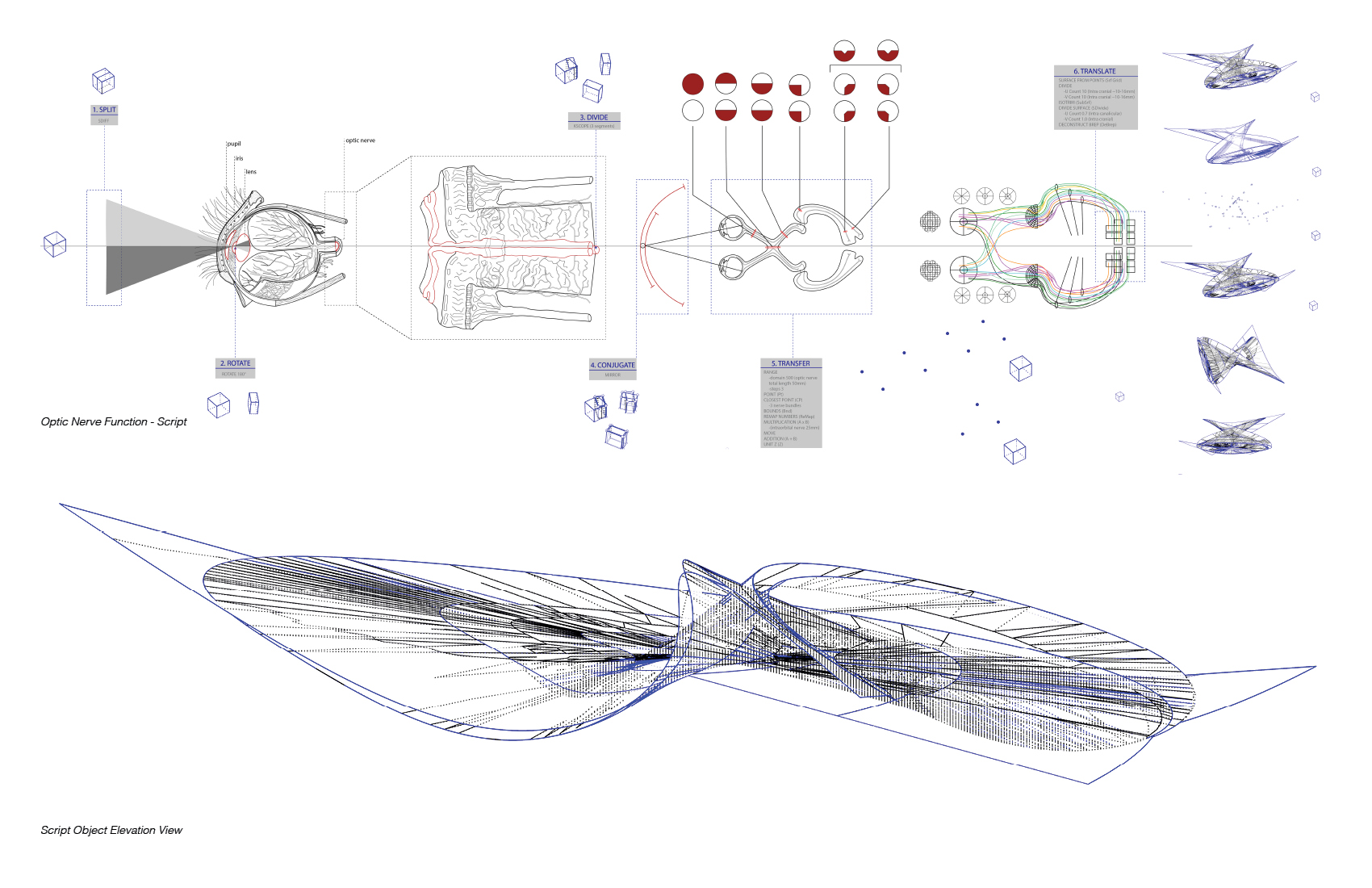

SCRIPTING + ALGORITHMIC DESIGN

Grid Space

Critic: Dorian Booth

The historical and contemporary organizational strategy of regulating frameworks to create formal relationships within the architecture field was analyzed. The grid as a drawing device and the grid as an organizational device were explored through the design of drawings through Grasshopper. The muscle movement and optic nerve functions of the eye were perceived as an organic ‘framework’. The movements of the organic framework were translated into a grasshopper script in which neutral objects were linked, forming a new object or placement.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

3D MODELING FOR CREATIVE PRACTICE

Critic: Justin Berry

In this virtual reality occulus class, students produced projects that took advantage of 3D modeling in different ways. Virtual reality and augmented reality manifestations were explored through different world building techniques in virtual reality and in 3d design computer programs. Each assignment engaged a different form of output, such as 3D printing, the photographic image, interactive space, and the illustration of imaginary worlds.

Historically, the way that the world is described to us has a tendency to change our understanding of the world. From the iconography of the first cave paintings, the tombs of ancient Egypt, the invention of perspective, the technology of the photograph, through to 3D modeling, each form of depicting the world has generated social and cultural shifts of profound relevance. We are in the midst of an explosion of new technologies and methods of image-making but central to these technologies is the absence of an authoritative viewpoint, as even the 3D printed object exists not as an original but as one of many possible versions.

![]()

![]()

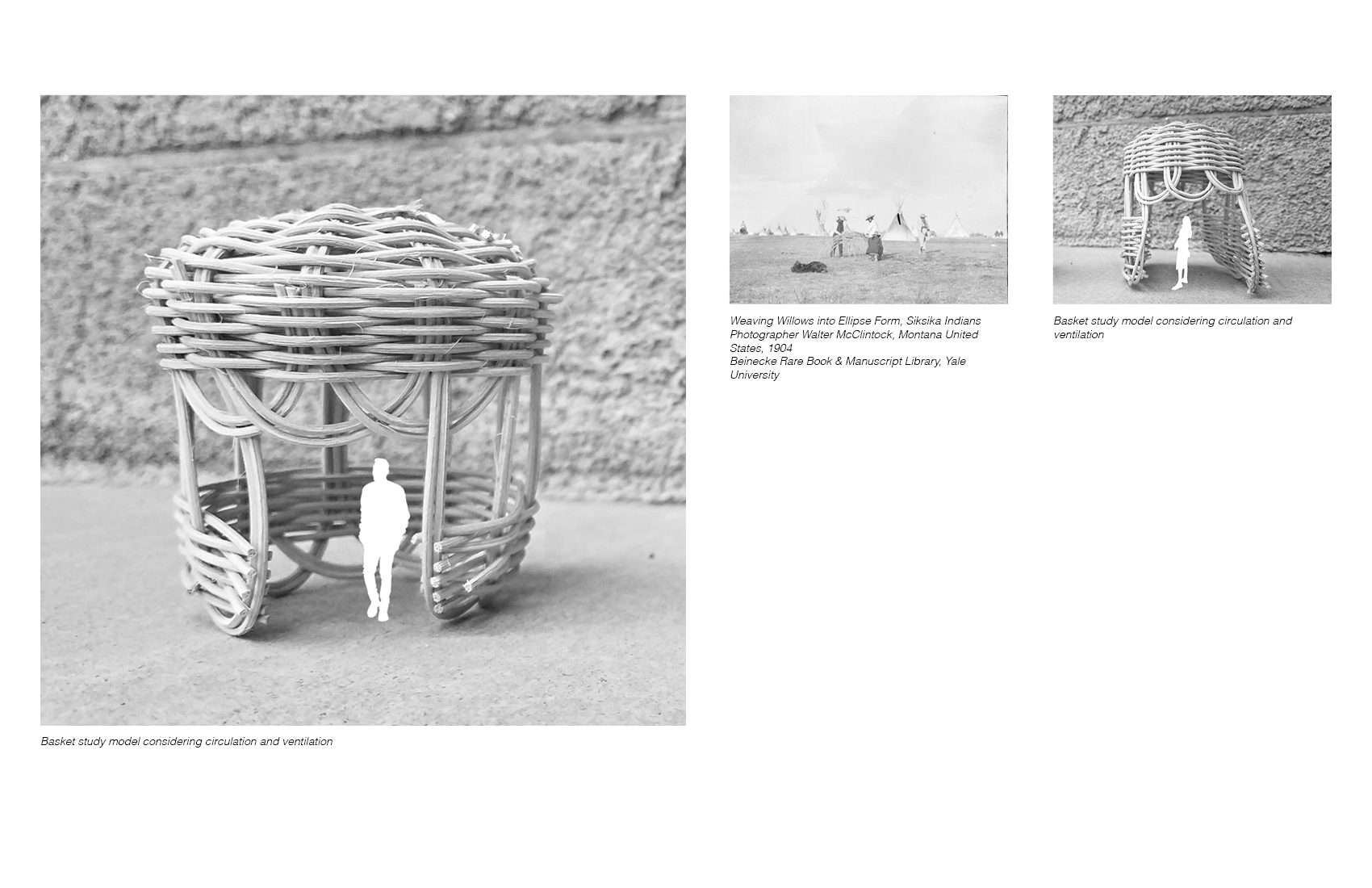

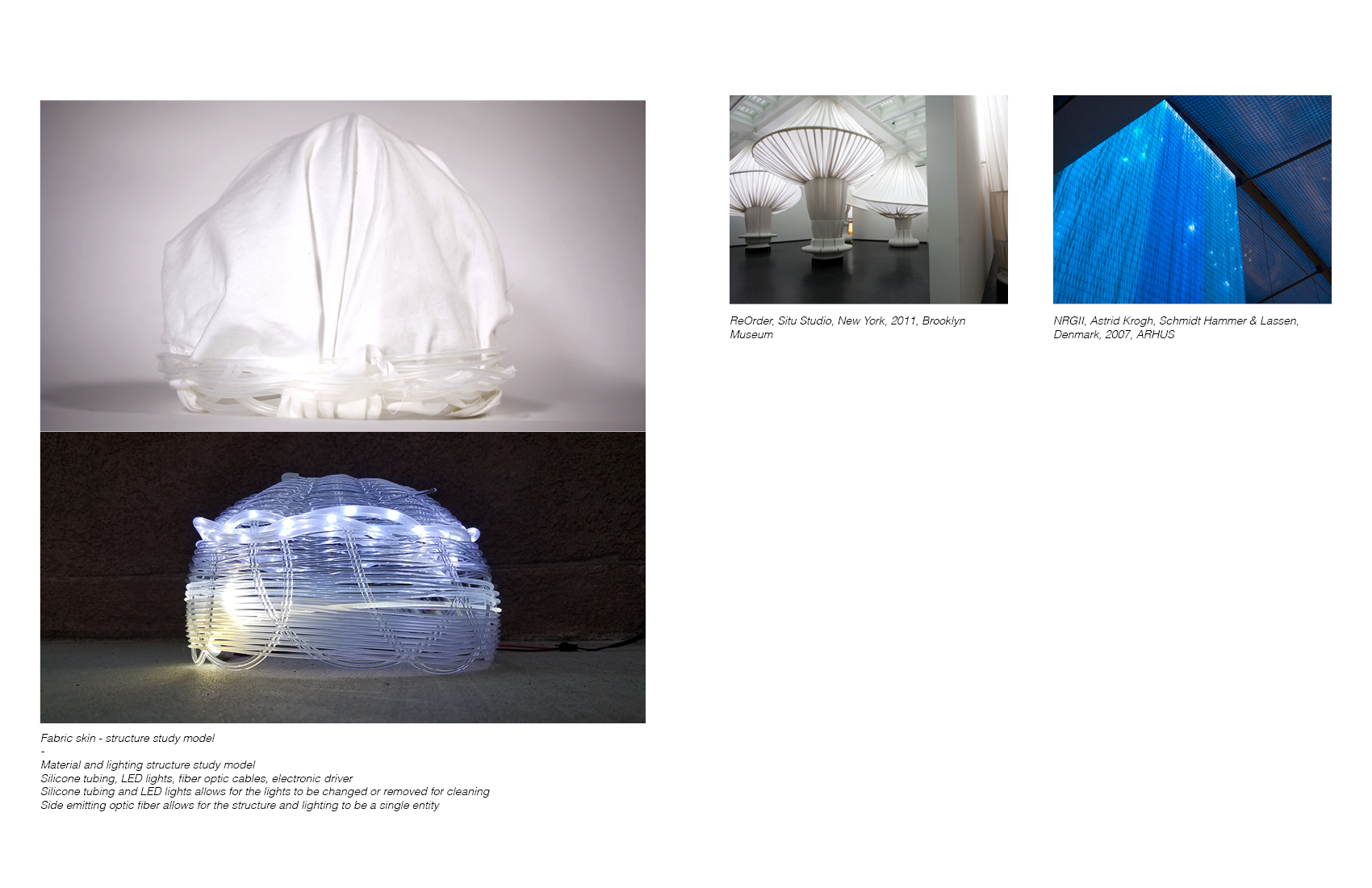

POWERHOUSE: TEXTILE ARCHITECTURE

Davies Toews Architecture

Researcher, Architectural Designer

Powerhouse is a collective of studio spaces housed in a previous Power Station Warehouse in Brooklyn, New York. The warehouse houses different creative studios including a textile studio. The textile studio was interested in incoporating textile architecture into the interior spaces of the studio. Textile history in relation to basket making, and Native American history were thoroughly researched and manifested into textile architecture structure models. Research and design culminated into a publication entitled, Textile Meanings + Experiments.

![]()

![]()

MAKING SPACE FOR RESISTANCE

North Gallery Exhibition

Indigenous Scholars of Architecture, Planning and Design at Yale

Co-Designer, Chief Curator, Constructor

Team: Charelle Brown, Anjelica S. Gallegos, Summer Sutton

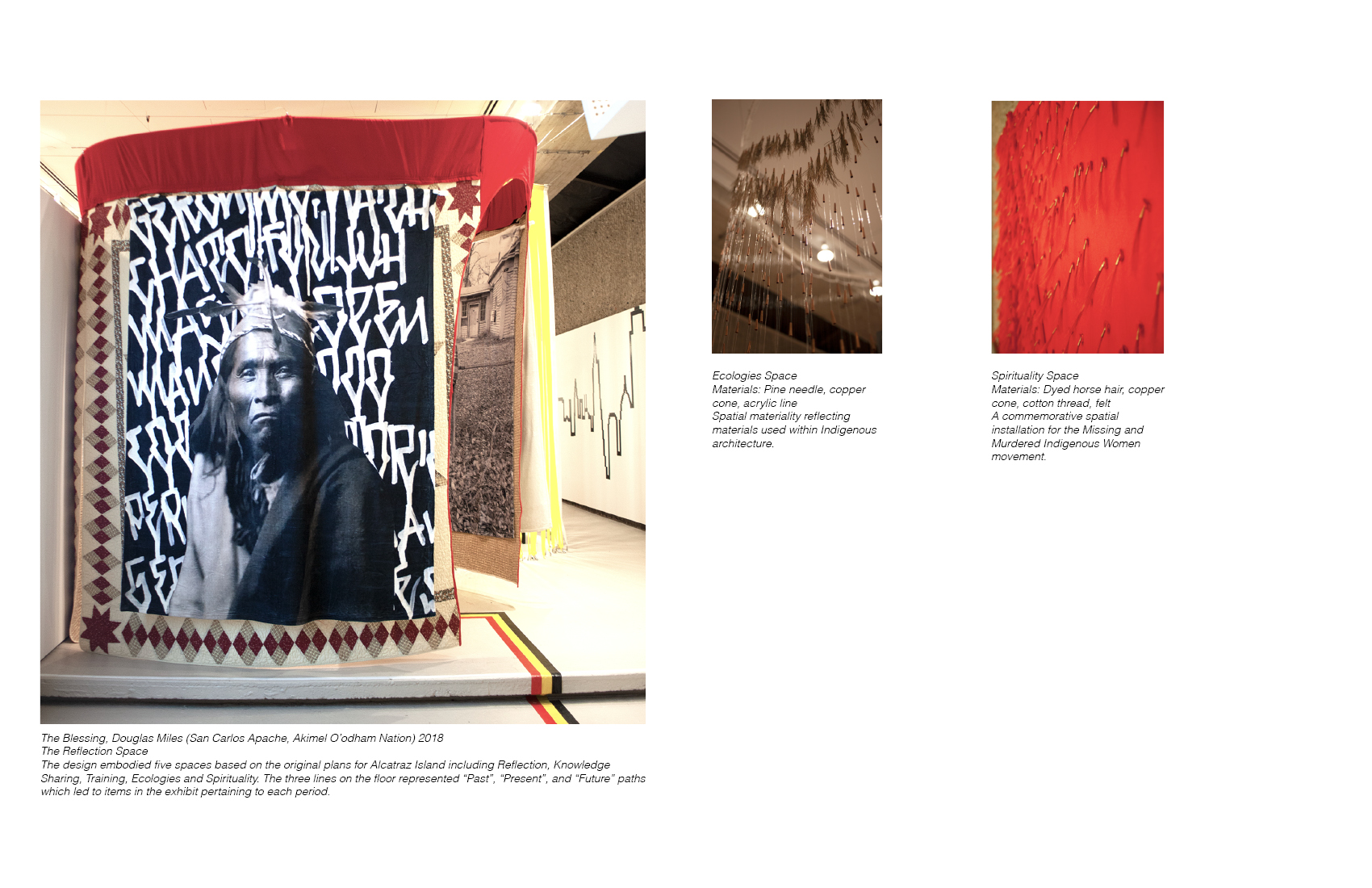

Each semester Yale School of Architecture selects three qualified student gallery exhibition proposals to be shown at the North Gallery for one month. The Indigenous Scholars of Architecture, Planning and Design, a student group I co-founded, proposed Making Space for Resistance: Past, Present, Future.

2019 marked the 50th Anniversary of the Alcatraz Island Occupation, an act of Indigenous resistance compelling justice and recognition of tribal self-determination and sovereignty. Architecture was fundamental to envisioning a brighter future for American Indians and catalyzing a cognizant American society. On December 23rd, 1969, in negotiations with the United States, the Indians of All Tribes Conference on Alcatraz Island presented a plan to design and build spaces for Indigenous resistance,redressing centuries of cultural repression. Although the Occupation helped to solidify an official U.S. policy of tribal self-determination and prompted increased focus and resources to American Indians, the plan to construct a gathering place for all tribal nations on Alcatraz Island was never fulfilled. Making Space for Resistance highlights past, present and future visions of Indigenous space connected to objectives expressed during the Occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969.

![]()

![]()

Los Angeles, CA (Craft Contemporary)

Co-Designer, Constructor

Team: Celina Brownotter, Anjelica S. Gallegos, Freeland Livingston, Selina Martinez, Bobby Joe Smith, Zoë Toledo.

We Carry the Land is an architectural exploration of space, time, and form born from an alignment of varied Indigenous foundational ways of being. Rooted in the sacredness of the natural world and informed by experiences of territorial geographic relocation, the project presents a spatial identity of what it means to be Indigenous in 2024; grounded, yet simultaneously flexible.

Through material and structural engagement with existing infrastructure, the project introduces a fluctuating experience of the sacred and intimate to the Craft Contemporary x M&A Courtyard. An existing circle inscribed in the courtyard’s concrete ground, the remnant of a primary entry revolving door for a building that once stood in the space, becomes an anchor for the spatial intervention. In its place, a new circle is built up with heavy earth and juxtaposed with the soft lightness of a flowing curtain system above. While the earthen material highlights the circle, a unifying symbol in various Indigenous cultures, the curtain system extends across the courtyard, representing expansive transformation and the dynamism of movements and exchanges between pasts and possible futures.

We Carry the Land is designed by six emerging Native architectural and graphic designers. Recognizing the diversity of Indian Tribes, individual identities, and shared experiences with U.S. Indian laws and policies, the group work reflects a coming together of unique communities, spatial experiences with multiple lands and waters, archival work, and traditional and new technologies. We Carry the Land presents the two-fold idea of anomaly: the paradoxical notion of a dynamic ground plane and the enduring presence of American Indian peoples despite efforts of erasure.

28 archival imagery and documents were curated by Anjelica S. Gallegos to project onto the We Carry the Land installation. The work covers the Los Angeles site’s historic relationship with Indigenous Peoples, environment, and architecture. Early Indigenous and colonial architecture, the 18 treaties of California, the use of natural resources of Indigenous groups for the development of Los Angeles, the Indigenous contributions toward the infrastructure and built environment of Los Angeles, and the Indian boarding school system legacy are shown.

As a program for Materials and Applications, throughout the summer of 2024, We Carry the Land included workshops, storytelling, shared meals, and other events cultivating community and kinship. Together with nearby and distant program partners, events centered on rethinking relationships to land through reorienting, reinforcing communal support through extending, and challenging and energizing ideas through Indigenous futuring.

THE EQUINOX HOUSE

Albuquerque, NM (Valle de Oro National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center)

New York City, NY (Davies Toews Architecture)

Co-Designer, Constructor

Team: Miriam Diddy, Anjelica S. Gallegos

The spatial installation is a temporal travel bound structure that embodies celestial alignment and foreshadows dwelling practices of an Indigenous future. Temporary construction techniques, regional materiality, textile practices, and directional alignment are composed to reignite architectural knowledge of seasonal shift and natural cycles in the Equinox House.

The north and south doors introduce the space and are framed with black rectangular folded felt, juxtaposing with the primary circular profile of the structure. The central column of the structure ties together internal and external elements, including the top exterior nylon skin with four apertures, representing the four winds. A multicolored woven textile representing the interconnection held with the universe was centered on top of the column while a beam on the east-west axis balanced the circular three-dimensional maps on each end. The three dimensional maps outlined and aligned with the star studded sky at sunrise and sunset, while the central column aligned with the sun at high noon, on the fall 2024 equinox that took place in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Regional materials and new lighting technologies shift based on the house’s location and visual narratives shared from community members. While the first site was the desertscape of Albuquerque and wetland of Valle de Oro, adobe, pine, juniper and cholla cactus were central to the space. For the urban north east coast location of New York City, oyster shells, moss, cattails, and water were embodied in the House.

Visual narratives of seasonal change and celestial alignment from the greater Indigenous community were projected onto the free standing structure harmonizing with the collective elements.

While in New Mexico, the House was primarily experienced in the arid day at the height of the Equinox in September. At the white gallery space in New York City, the House was activated at night in late October complementing the coastal reflective surfaces of the urban landscape.

The Equinox House was designed and constructed on site by Anjelica S. Gallegos and Miriam Diddy as part of the larger First Future Project. The endeavor was awarded a Fulcrum Fund grant made possible by 516 Arts as a partner in the Regional Regranting Program of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

The Equinox House is now located with the ISAPD Yale chapter for another future adaptation.

Nantucket, MA

Remain Nantucket initiated the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Initiative (IKSI) to respectfully acknowledge Indigenous historical and contemporary ties to the Envision Resilience Challenge sites.

The IKSI Working Syllabus provides curated resources for Envision Resilience Challenge participants and the general public to strengthen design approaches as we move forward in informed stewardship with all communities.

IKSI was created with the support of Anjelica S. Gallegos (Jicarilla Apache Nation/Santa Ana Pueblo), a member of the first Envision Resilience Challenge student cohort, Advisor of the Envision Resilience Challenge and Director of the Indigenous Society of Architecture, Planning and Design.

https://www.envisionresilience.org/iksi

MAINE TRIBAL LANDS

Remote Location

Private Client

YALE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE TRIBAL LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

New Haven, CT

Project Origin:

This project was initiated as a collaborative effort between Indigenous Scholars (Society) of Architecture, Planning and Design co-founders Anjelica S. Gallegos (MArch I ’21) with Summer Sutton (Architecture PhD ’22), and Dean Deborah Berke, and Yale School of Architecture leadership. The project was accomplished with the support of the Yale Native American Cultural Center and Yale student members from classes 2019 to 2024.

Yale School of Architecture Tribal Land Acknowledgement Statement:

The Yale School of Architecture sits on traditional Indigenous territories. This includes lands of the Mohegan, Mohican, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic, Quinnipiac, and other Algonquian speaking peoples. We pay respect to their peoples of past and present.

Yale University and Yale School of Architecture have benefitted from lands gained through fulfilled and unfulfilled articles of agreement with Indigenous nations and from land cession of Indigenous territories.

The Indigenous peoples who have stewarded these lands for time immemorial remain impacted by discussions of space and place. Yale School of Architecture will continue to work, advance, and teach these histories in architectural education and the profession.

As mediators, we will learn from the generations before us to instill cognizant ways of being in spatial environments with shared histories. As architectural professionals, we will imagine endless possibilities for architectures of reconciliation, reciprocity and transformation; an architecture for those yet to be born, an architecture of the spirit.

Drawing Intention:

This interpretive map presents interconnected boundaries of tribal land over time and their relationship to the New Haven area. Animate and inanimate entities are woven throughout the landscape as a cohesive system.

The orthogonal lines coming from the west, north and east, connect to the center of New Haven’s nine square grid, and indicate the historical Quinnipiac travel routes that linked the Quinnipiac with the Paugussetts, Wangunk and Mattabesett, Hammonasset and Niantic peoples.

The topography lines above the nine square grid, represent Hobbomock mountain, now known as Sleeping Giant. Hobbomock mountain is a landmark and significant place within Quinnipiac origin stories and connected with surrounding New Haven topography history.

https://www.architecture.yale.edu/about-the-school/tribal-land-acknowledgement

PLAN, UNPLANNED

Contemporary Art Museum

New Haven, CT

Architectural Design Studio I

Critic: Nikole Bouchard

The importance of design through the plan was studied in depth during this studio. An original drawing inititated the project and was sourced as a collection of geometric forms to organize into a building form. Ultimately the plan as a tool to create spatial and social relationships was realized and strengthened. Tectonic and material specificity, site context, sun movements, ecology design, and occupation were key components in the design of the Contemporary Art Museum.

RESTORATIVE COMMUNITY

The People’s Land Center

New Haven, CT

Architectural Design Studio III

Critic: Emily Abruzzo, Inaqui Carnicero

The unique history, current and future needs of the New Haven site was thoroughly researched for the design of an ecological community center. Gathering information from 19th century scholar and previous Yale President Ezra Stiles, a map of New Haven based on information from interviews with the original Indigenous peoples of the land was created with the original context of the site, noting shorelines, trails used by tribes. Further, I investigated the historical changes of the shoreline of on the harbor adjacent to the site and collected data on the future changes of the shoreline due to climate change. In an effort to generate a mutually restorative relationship with the natural environment, like the original land stewards had, a program centered around adaptability, learning and implementing practices related to horticulture, agriculture, water harvesting and forest restoration was established. To address current needs an open floor plan for all levels was carefully organized to incorporate needs such as immigration services. A series of man made land mounds were created to address the future need for land mass and a place to congregate.

LIFE, AFTERLIFE

Indigenous Horticulture Center

Manhattan, NY

Architectural Design Studio II

Critic: Trattie Davies

The permanence of buildings and life of materials was the focus of this studio. Designers were asked to consider how the design would change over the course of 100 years. I researched the historical context of the site including the indigenous horticulture practices used to grow food and allow for reforestation of the land. I analyzed the site changes over the next 100 years incorporating the future tide changes due to climate change. Tectonic principles in basketry and tensile structures were used as precedence for construction.

CITY, RENEWED

The Nature Culture Nexus Plan

New York, NY + Bronx, NY

Urban Design Studio IV

Critic: Bimal Mendis

The dependency humans have on the ecological environment has been ubiquitous for time immemorial and yet many natural processes are unacknowledged and often directly contradicted by human activities. The loss of ecological consciousness is an urban crisis and stems from the coupled erasure of ecological knowledge and forced displacement of the communities who know these environments thoroughly; the Indigenous communities.

The Nature-Culture Nexus Plan restores the Indigenous knowledge and practices of historical ecological consciousness of Inwood, Manhattan and Fordham Landing, Bronx by revealing the unseen interdependencies with the natural world recharging the reciprocal relationship between the collective of people, animals, plants, fungi and ecosystems, ultimately reengaging the built environment with the natural environment. The plan is designed to be a framework to sow across both ecosystems and urban places, while recognizing and strengthening the unique histories and current conditions of each site. The plan is carefully complementary to sustainable policy including the Green New Deal and the Pollinator Protection Plan of New York State. Weaving community, state and federal partners and programs strengthens the collective and provides new knowledge and application. The seven step plan includes methodology within Indigenous traditional knowledge covering, cultural resources, responsive landscape technology, site heritage and cross-pollinating programming.

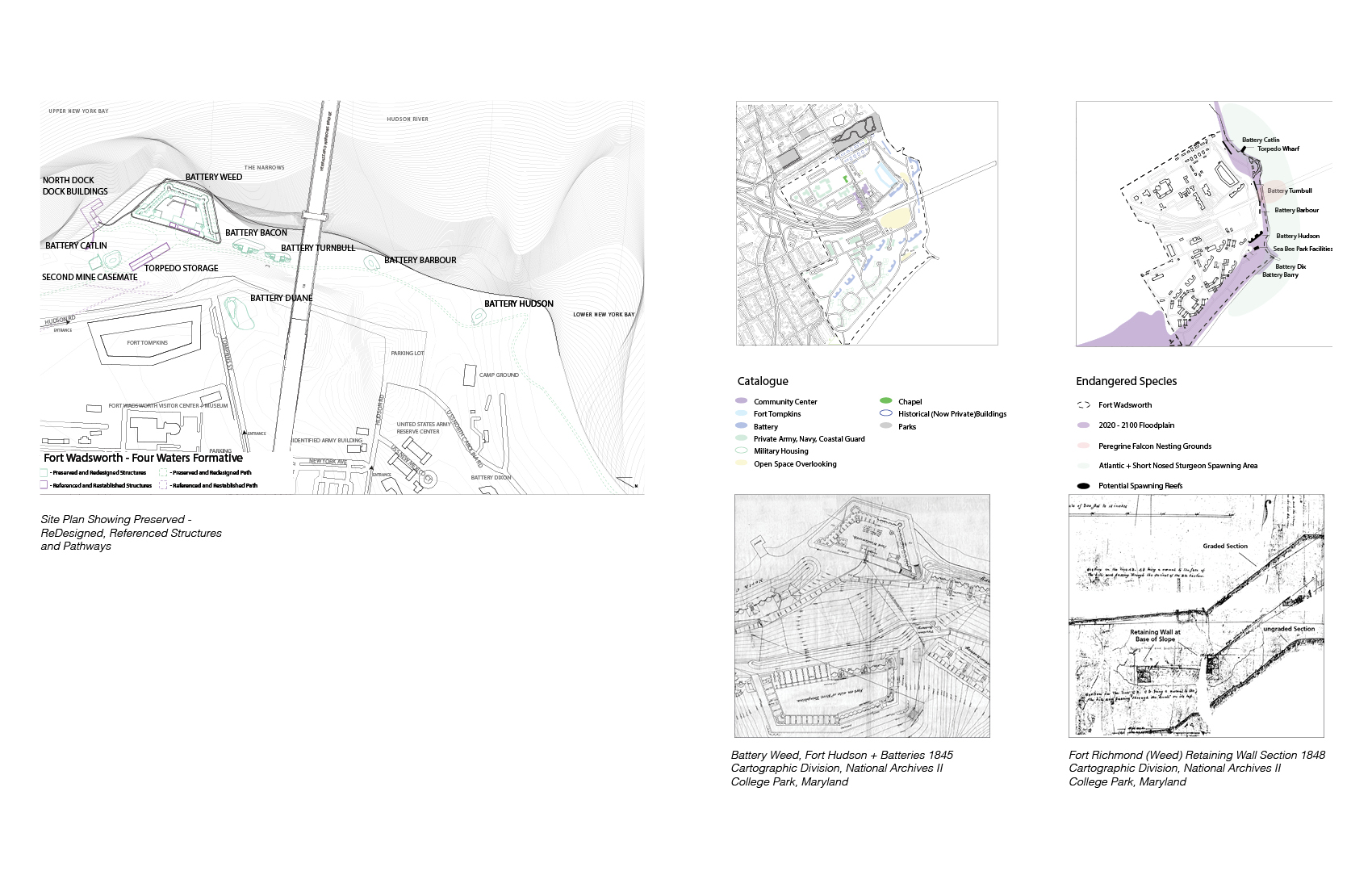

PRODUCTIVE UNCERTAINTY: INDETERMINANCY, IMPERMANENCE AND THE ARCHITECTURAL IMAGINATION

Four Waters Formative: A Living Laboratory

Staten Island, NY

Advanced Design Studio V

Critic: Marc Tsurumaki, Violette de la Selle

The fundamental paradox of uncertainty for a discipline based on projection, of impermanence for a practice predicated on permanence, defined the studio. The studio proposed how the material conditions of architecture might engage with the increasing volatility that characterizes our collective relationship to emergent environmental, climatological, biological, political and social conditions.

Four Waters Formative is a Living Laboratory for Indigenous ecological knowledge integrating adaptive design, land remediation and historical preservation. Fort Wadsworth (renamed Four Waters Formative) is on Staten Island and is part of the Gateway National Recreation Area as a National Park and is considered federal land. Four Waters Formative acts as a reinterpreted National Park and histrocially preserved military site, with on site education and a place to promote collaboration between the greater public, tribes and federal programs. The program centers around the the Stronghold as a gathering place while the path system weaves together interventions including gazing pods, artificial reefs, pollinator batteries, earth work, Shatemuc Pavilion, the Deer House, the Longhouse, Falcon Bridge and the American Indian Monument; a data collector and visual indicator of live environmental information. Membrane as a means of perception, the gaze, and fortification and various indigenous design principles were explored throughout the project.

COASTAL NEW ENGLAND: HISTORY, THREAT AND ADAPTATION

New England Foodways: Reconnecting Nantucket with Traditional Cultures of Water, Land and Food

Nantucket, MA

Advanced Design Studio VI

Critic: Allan Plattus, Andrei Harwell

Team: Anjelica Gallegos, Daoru Wang, Robin Yang

Along with four other universities, Yale School of Architecture, was invited by ReMain Nantucket, an island-based non-profit, to participate in a collaborative studio exploring design approaches to wide-ranging challenges of coastal resilience and adaptation, cultural heritage, and environmental justice. This studio will consider broadly the natural and human landscape of coastal New England, with a specific focus on the island of Nantucket and related coastal sites.

Our project has three main focus areas including adaptation, rebalance, and the regional food network. From the indigenous peoples, to the maritime quakers, the spirit of Nantucket has been to embrace challenges and recognize potential. We propose a new circular economy centered around aquaculture. Responding to sea level rise, flooding, and coastal erosion, we use modes of regeneration, mitigation, and migration to focus on incremental adaptation.

Allowing and strengthening the natural infrastructure to fully function creates reciprocity, is economically wise, and has concrete benefits. We introduce a range of dynamic landforms to mitigate rising waters at different time periods, including extending the beach, introducing sand dunes, and restoring eelgrass beds. The main artery of the raised infrastructure will be Beach Street, where a series of boardwalks will reach to the harbor edges of Brant Point.

Nantucket is part of the second largest United States aquaculture producing region and is part of New England’s network of diverse aquaculture. The increasing subtidal zone along Brant Point can become the new commons of Nantucket, where people have access to cultivate their own aqua gardens to grow and eat from. A sea market and processing center will invite the public to taste Nantucket’s unique foods and show different processing techniques. As the tides rise, two new housing types: the tower-house and cliff co-op will be introduced. Brant Point can lead the growing shift toward regenerating community connection with the land, eating from sources closer to the region, and evolving balanced maritime living.

FORMAL ANALYSIS

Critic: Peter Eisenman

Learning to see and read as an architect was inititated through this course as a series of weekly texts and analyses that move from the theocentric late - medieval, to the humanism and anthropocentricty of the early Renaissance, to the beginning of the Enlightenment of the late eighteenth century. Based on the texts an argument was constructed about the spaces and shown through drawing.

AFTER THE MODERN MOVEMENT

Critic: Robert A. M. Stern

This course aimed to answer the questions, What was and What is postmodernism in architecture? Postmodernism should not be seen as a style, but rather as a condition reacting to the ahistorical, acontextual, self-referential materialism that orthodox modernism had come to represent in the post–World War II era.

Students are conceptualized and design a facade in the manner of a chosen architect for an alternative Strada Novissima. In the design of the facade, students adhered to the same brief given to the Strada Novissima participants in the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale.

According to David Chipperfield, we must maintain the identity of places. The preservation of history tells a society who they are today. Individual buildings do not encapsulate a society’s character or the character of a place themselves, rather the collected composition of buildings and the connecting streets weave the urban fabric together in an influential timeline where the past influences the present. I treated the given elements as a historical structure which needed a level of protection and restoration. Therefore, I preserved the four existing columns, original identified grid and visual access to the windows. I consider the current social dynamic of the street as an important context for the facade to have a conversation with, allowing circulation from the street to enter the exhibition area through the columns. I respected the current grid system and restored two columns which used to be there. Additionally, I restored the facade. The intention was not to replicate the past facade but rather allow its presence to be felt and respected by using harmonizing foundational forms and materials of similar hued marble and recycled handmade brick. The heritage of the facade is preserved and protected while presented in unison with a concurrent architectural identity.

JIM VLOCK BUILDING PROJECT -

BUILDING INFORMATION MODELING

Critic: Alan Organschi , Julie Zink

Team: Anjelica Gallegos, Kevin Gao, Ashton Harrell, Niema Jafari, Leanne Nagata

The Yale Building Project of 2019 collaborated with the Columbus House of New Haven to articulte and design 3 units for previously homeless individuals. 1300 sq ft apartments were designed to include living, bedroom, bathroom, kitchen and shared mechanical systems, waste, recycle and outdoor garden space. The class focused on garnering a deep understanding and skill level with BIM platform Revit. The management of work flows and model integrity while understanding the interrelationships of working on a virtual live model with other designers was paramount.

SCRIPTING + ALGORITHMIC DESIGN

Grid Space

Critic: Dorian Booth

The historical and contemporary organizational strategy of regulating frameworks to create formal relationships within the architecture field was analyzed. The grid as a drawing device and the grid as an organizational device were explored through the design of drawings through Grasshopper. The muscle movement and optic nerve functions of the eye were perceived as an organic ‘framework’. The movements of the organic framework were translated into a grasshopper script in which neutral objects were linked, forming a new object or placement.

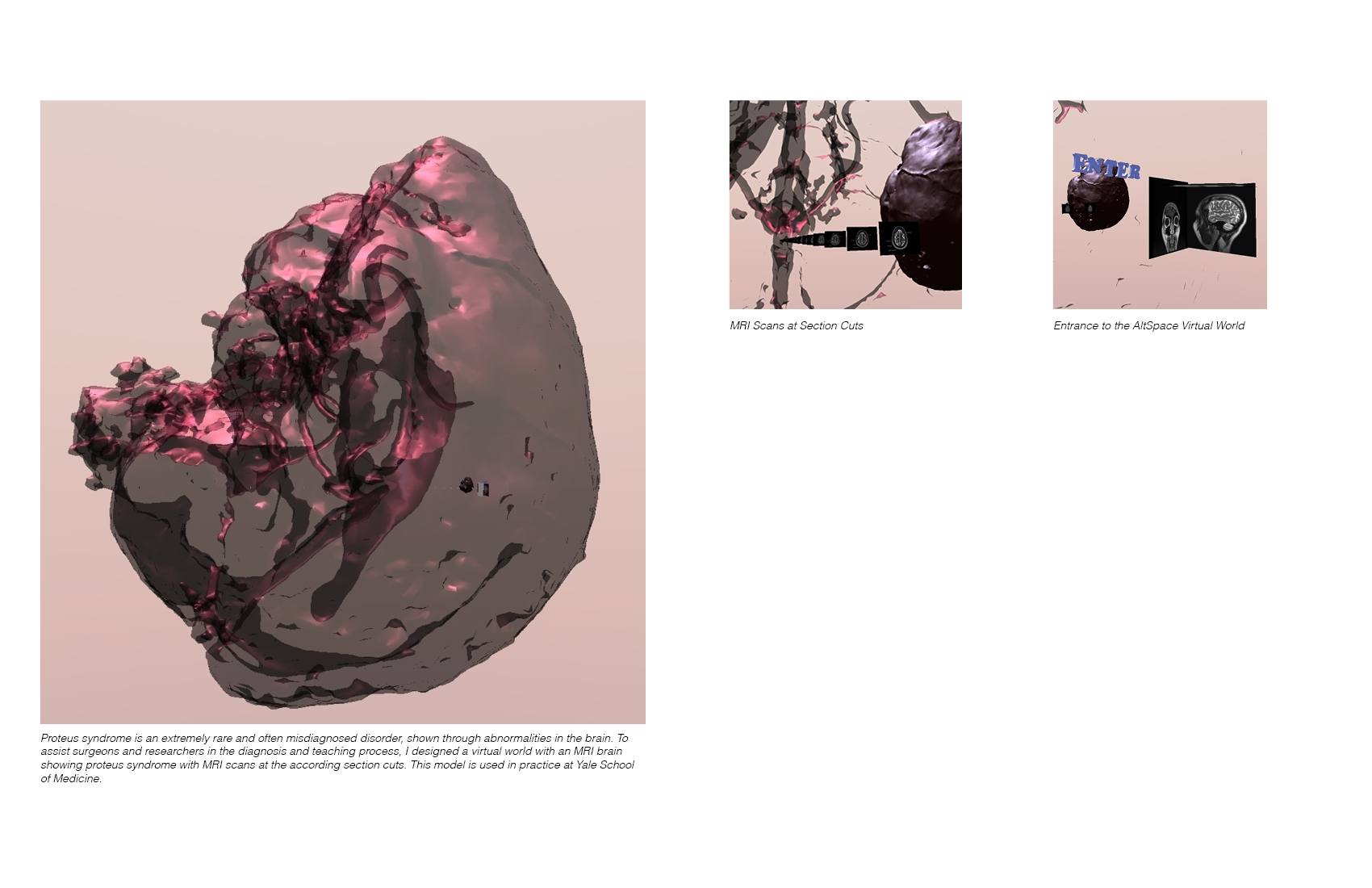

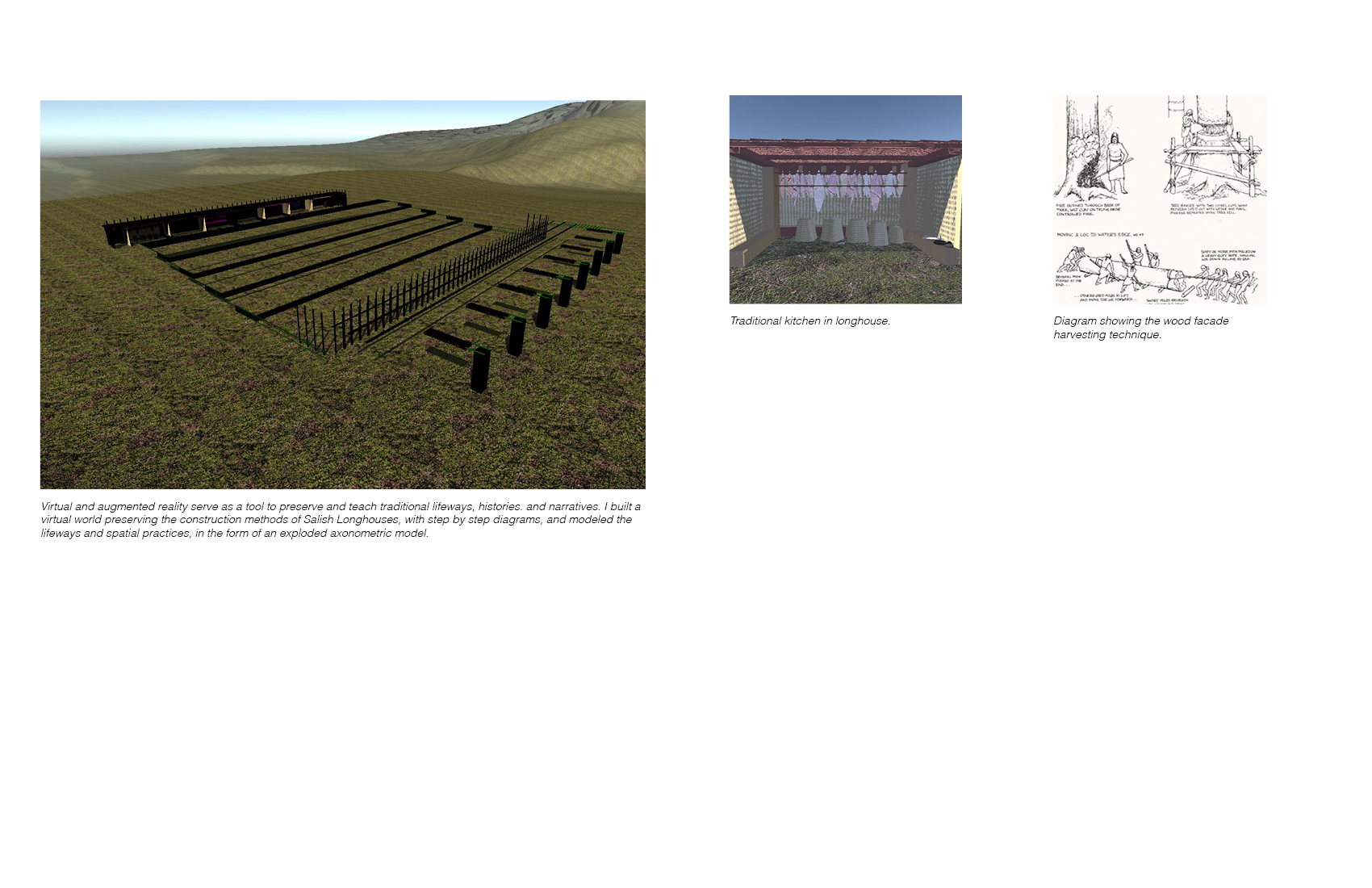

3D MODELING FOR CREATIVE PRACTICE

Critic: Justin Berry

In this virtual reality occulus class, students produced projects that took advantage of 3D modeling in different ways. Virtual reality and augmented reality manifestations were explored through different world building techniques in virtual reality and in 3d design computer programs. Each assignment engaged a different form of output, such as 3D printing, the photographic image, interactive space, and the illustration of imaginary worlds.

Historically, the way that the world is described to us has a tendency to change our understanding of the world. From the iconography of the first cave paintings, the tombs of ancient Egypt, the invention of perspective, the technology of the photograph, through to 3D modeling, each form of depicting the world has generated social and cultural shifts of profound relevance. We are in the midst of an explosion of new technologies and methods of image-making but central to these technologies is the absence of an authoritative viewpoint, as even the 3D printed object exists not as an original but as one of many possible versions.

POWERHOUSE: TEXTILE ARCHITECTURE

Davies Toews Architecture

Researcher, Architectural Designer

Powerhouse is a collective of studio spaces housed in a previous Power Station Warehouse in Brooklyn, New York. The warehouse houses different creative studios including a textile studio. The textile studio was interested in incoporating textile architecture into the interior spaces of the studio. Textile history in relation to basket making, and Native American history were thoroughly researched and manifested into textile architecture structure models. Research and design culminated into a publication entitled, Textile Meanings + Experiments.

MAKING SPACE FOR RESISTANCE

North Gallery Exhibition

Indigenous Scholars of Architecture, Planning and Design at Yale

Co-Designer, Chief Curator, Constructor

Team: Charelle Brown, Anjelica S. Gallegos, Summer Sutton

Each semester Yale School of Architecture selects three qualified student gallery exhibition proposals to be shown at the North Gallery for one month. The Indigenous Scholars of Architecture, Planning and Design, a student group I co-founded, proposed Making Space for Resistance: Past, Present, Future.

2019 marked the 50th Anniversary of the Alcatraz Island Occupation, an act of Indigenous resistance compelling justice and recognition of tribal self-determination and sovereignty. Architecture was fundamental to envisioning a brighter future for American Indians and catalyzing a cognizant American society. On December 23rd, 1969, in negotiations with the United States, the Indians of All Tribes Conference on Alcatraz Island presented a plan to design and build spaces for Indigenous resistance,redressing centuries of cultural repression. Although the Occupation helped to solidify an official U.S. policy of tribal self-determination and prompted increased focus and resources to American Indians, the plan to construct a gathering place for all tribal nations on Alcatraz Island was never fulfilled. Making Space for Resistance highlights past, present and future visions of Indigenous space connected to objectives expressed during the Occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969.